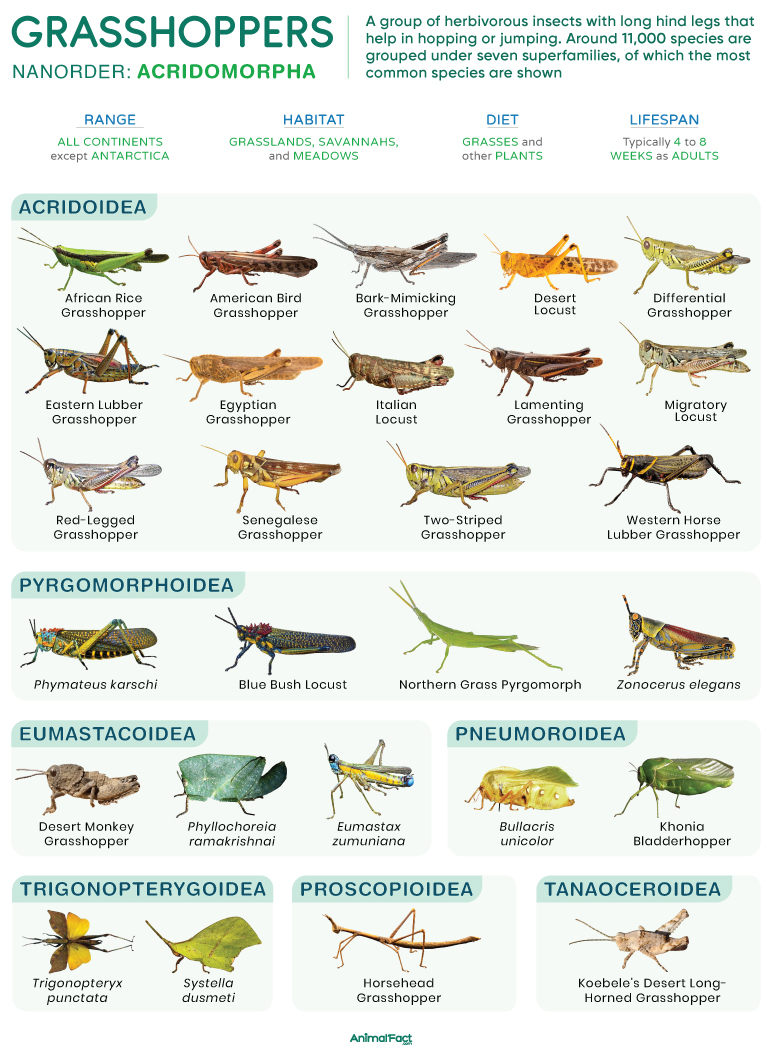

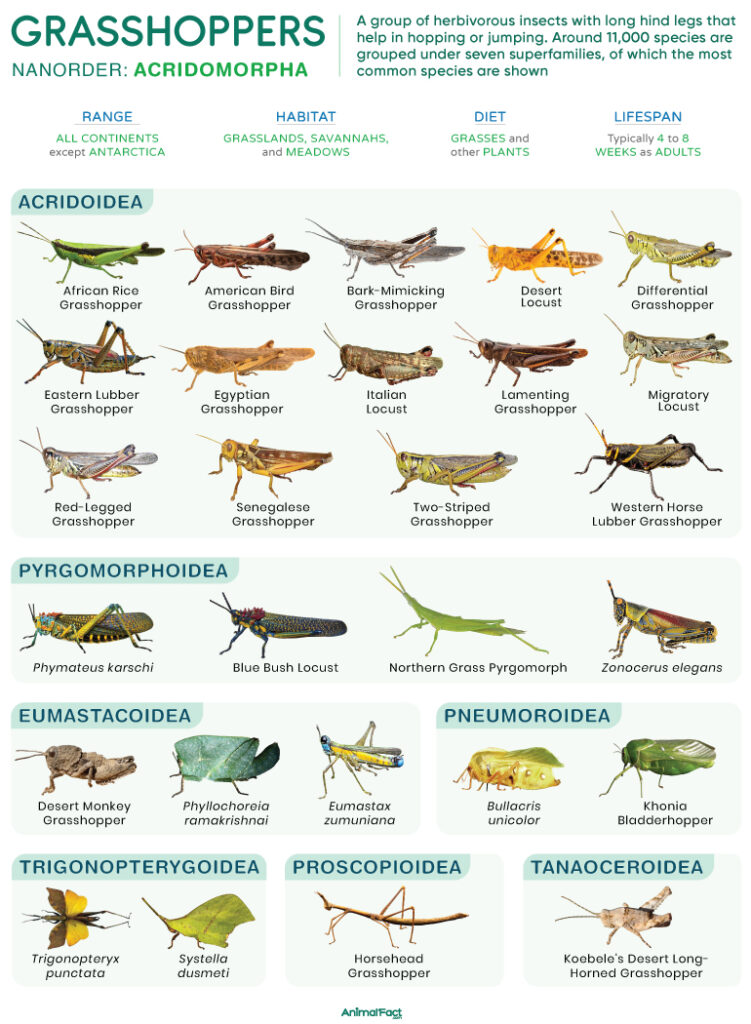

Grasshoppers are a group of herbivorous insects that constitute the nanorder Acridomorpha within the suborder Caelifera. They have notably long hind legs that enable them to leap impressive distances. Another distinctive feature is the presence of an auditory organ, the tympanal organ, on the abdomen, rather than on the head.

An ancient group dating back to the Early Triassic Period (around 250 million years ago), these insects are found almost everywhere in the world except Antarctica. They prefer living in open habitats, such as grasslands, savannahs, and meadows, where they feed on grasses and the leaves of various plants, including peas, corn, and wheat.

Though grasshoppers are typically solitary, some species, known as locusts, can undergo behavioral changes and form swarms of millions of individuals. As they migrate, these swarms consume all vegetation in their path, inflicting severe agricultural damage.

On average, grasshoppers range from 0.4 to 2.8 in (1 to 7 cm) in body length.[1] However, one of the largest species, the giant red-winged grasshopper (Tropidacris cristata), can grow up to 5.7 inches (14.5 cm) in length. In contrast, among the smallest species, the Sigaus minutus measures only about 0.35 to 0.4 in (9 to 10 mm).

Like other insects, grasshoppers have a tripartite (three-part) body plan, comprising three segments: head, thorax, and abdomen. A chitinous exoskeleton or the cuticle covers all the body segments.

The head of a grasshopper is held vertically at an angle to its body. It bears a pair of long, thread-like antennae and a pair of compound eyes that provide a wide field of vision. Additionally, there are three small, simple eyes (ocelli) that help in light detection.

The mouthparts are downward-directed and are adapted for chewing, with strong mandibles. There are two sensory palps located in front of the jaws.

The three thoracic segments, the pro-, meso-, and metathorax, are fused, with each bearing three pairs of legs. The mesothorax bears a pair of narrow and leathery forewings (tegmina), while the metathorax has a pair of large, membranous hindwings.

Each leg bears five segments: coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, and tarsus. The tarsus bears three to five subsegments, with the final segment bearing two sharp claws (one on each side). The claws help the grasshopper cling to surfaces effectively.

The abdominal region has 11 segments, of which the first one is fused with the thorax and bears the hearing organ, the tympanal organ. This organ has a thin, stretched membrane called the tympanum that vibrates in response to sound waves. These vibrations get transmitted through internal air sacs to the sensory neurons, which send signals to the insect’s brain.

Segments 2 to 8 are ring-like, while segments 9 to 11 are relatively reduced. The 9th segment bears a pair of cerci, whereas the 10th and 11th segments bear the reproductive organs.

They have an open circulatory system, in which the hemolymph bathes the internal organs of the hemocoel directly, without the need for closed vessels. The hemolymph carries nutrients, hormones, and metabolic wastes throughout the body.

Like most insects, grasshoppers possess a network of air-filled tubes called tracheae, which open to the exterior through numerous valved openings, known as spiracles, on their bodies.

The digestive tract of grasshoppers comprises a fore-, mid-, and hindgut. The foregut constitutes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, crop (a storage chamber), and gizzard. The gizzard is composed of chitinous teeth or plates, which help in the mechanical grinding of food.

The midgut comprises the stomach, lined with finger-like projections called gastric ceca, which increase surface area for absorption of nutrients.

Between the midgut and hindgut lie the Malpighian tubules, which function as kidneys and help direct nitrogenous waste into the hindgut for expulsion.

The nervous system of a grasshopper consists of a cerebral ganglion (homologous to the brain) located above the esophagus, from which a pair of ventral nerve cords extends along the body. Below the esophagus lies a subesophageal ganglion, which innervates the mouthparts.

The thorax and the abdomen possess segmental ganglia, from which peripheral nerves branch out into the body to supply various muscles and sensory organs.

Apart from the eyes and the tympanal organ, grasshoppers are equipped with other sensory structures. Their entire body is covered with numerous fine hairs or setae, which act as mechanoreceptors and help sense the surroundings. These setae are most dense on the antennae, the palps, and the cerci.

The leg joints of these insects possess chordotonal organs, which comprise groups of sensory cells that detect joint movement and limb position, assisting in coordinated movement.

The name of the suborder, Caelifera, derives from Latin, which translates to ‘chisel-bearing’, referring to the distinct shape of the ovipositor found in segment 9 of female grasshoppers.

Around 11,000 species are grouped under 7 superfamilies.

Grasshoppers are found on every continent except Antarctica and inhabit a wide variety of terrestrial environments. Most species are found in grasslands, arid and semi-arid zones, and the edges of lowland tropical forests.

These insects prefer open habitats replete with grasses and herbaceous plants.

They are herbivorous insects that primarily feed on grasses and leaves of various plants, including peas, alfalfa, corn, soybeans, and wheat. However, some species, such as the western horse lubber grasshopper (Taeniopoda eques), are omnivores and feed not only on plant matter but also on animal carcasses (necrophagy).[2]

When resources are scarce, some species, such as the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria), cannibalize on their conspecifics.[3]

These insects are exceptionally good at jumping and may do so to launch themselves into flight, move from one place to another, or flee from predators. Large grasshoppers, such as locusts, leap about 10 times their body length in a vertical jump and 20 times their length (almost 1 m) horizontally.[4]

They initiate a jump by extending their powerful hind legs backward against the substrate. This action generates a reactive force that launches them straight into the air.

Many grasshoppers, particularly males, rhythmically rub a row of peg-like serrations on the hind legs against the edges of their folded forewings, producing a distinct click-like sound, which typically serves in communication. These sounds help convey the sexual receptivity of the males and attract potential mates.

Some species may even stridulate to ward off other males from their territory.

Some species of the family Acrididae, commonly known as locusts, can switch from a solitary lifestyle to a highly gregarious swarming phase in response to environmental conditions. For instance, increased tactile stimulation of the hind legs through crowding causes these grasshoppers to change colour, feed more, and breed faster. These changes enable them to form dense, migratory swarms, often comprising millions of individuals. Members of the swarms produce pheromones that help attract more locusts to the lot, eventually expanding into multiple generations in a year.

These swarms are highly destructive, consuming nearly all vegetation that comes across their path.

Depending on the species, grasshopper adults typically live around 4 to 8 weeks (1 to 2 months).

To attract females for mating, male grasshoppers stridulate, producing species-specific calling songs. Once a pair forms, the male deposits sperm into the female’s reproductive tract. Depending on the species, copulation may last for a few minutes to about a day.[5]

After mating, the female digs a hole in the soil using the ovipositor and eventually lays her eggs, typically in summer. The eggs are laid in clusters known as egg pods, each containing 10 to 300 eggs, depending on the species. In some species, such as the western horse lubber grasshopper, the female ejects a liquid into the pod, which dries and forms a hard, protective case surrounding the eggs.[6] Although most species lay the eggs in the soil, some, such as Cornops aquaticum, deposit the pod directly into plant tissue.[7]

Typically, a few weeks into development, the eggs of temperate species enter a resting phase (diapause), resuming their development only after winter passes. When conditions are favorable, they hatch into nymphs.

The nymphs resemble miniature, wingless adults and typically undergo 5 to 6 molts, with their wing buds increasing in size at each stage. After the final molt, the nymph transforms into an adult, with the wings inflating and becoming fully functional. Depending on the species and environmental conditions, the development from nymph to adult takes a few weeks to months to complete.

Grasshoppers face numerous predators throughout their life cycle, from eggs to adults. Adults are commonly hunted by birds such as sparrows, crows, starlings, and swallows. Reptiles like skinks and geckos also prey on them, while amphibians, particularly frogs and toads, lap them up with their sticky tongues. Moreover, ants, robber flies, sphecid wasps, and spiders also feed on adults. Some small mammals, including shrews, mice, hedgehogs, and bats, also feed on grasshoppers opportunistically.[8]

Bee-flies, ground beetles, and blister beetles consume grasshopper eggs.

These insects are parasitized by mites, particularly those of the genus Eutrobidium, and nematodes, such as the grasshopper nematode (Mermis nigrescens) that lives in the hemocoel of the insect’s body.[9][10] Some parasitic worms, such as Spinochordodes tellinii and Paragordius tricuspidatus, also live within the bodies of grasshoppers.

Their eggs and nymphs are vulnerable to parasitoids, including blow flies, flesh flies, and tachinid flies.