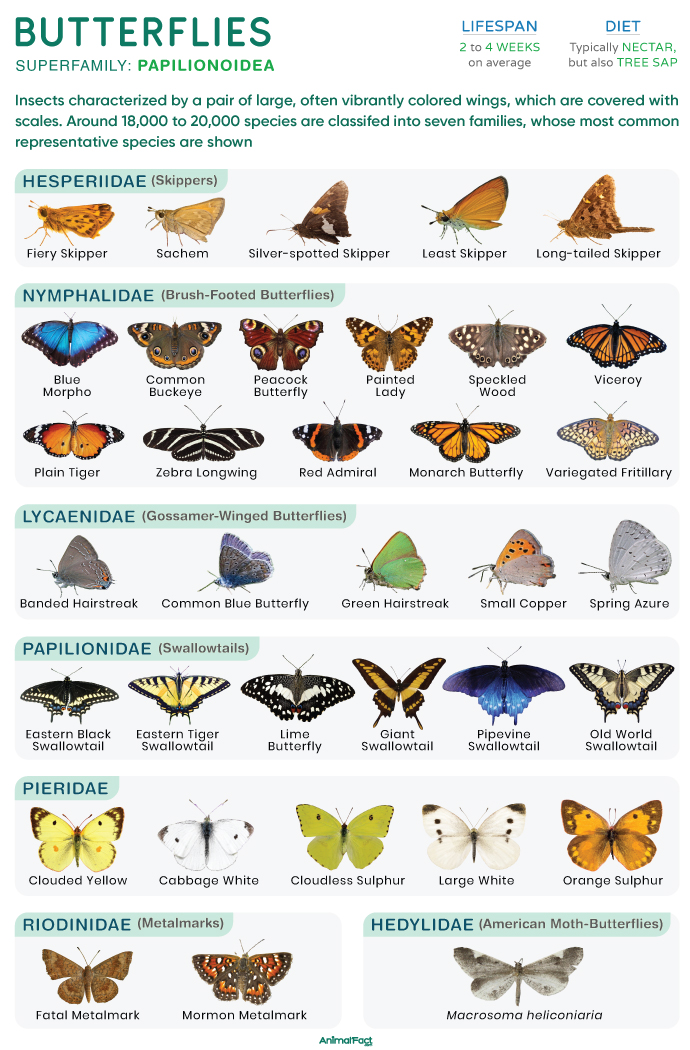

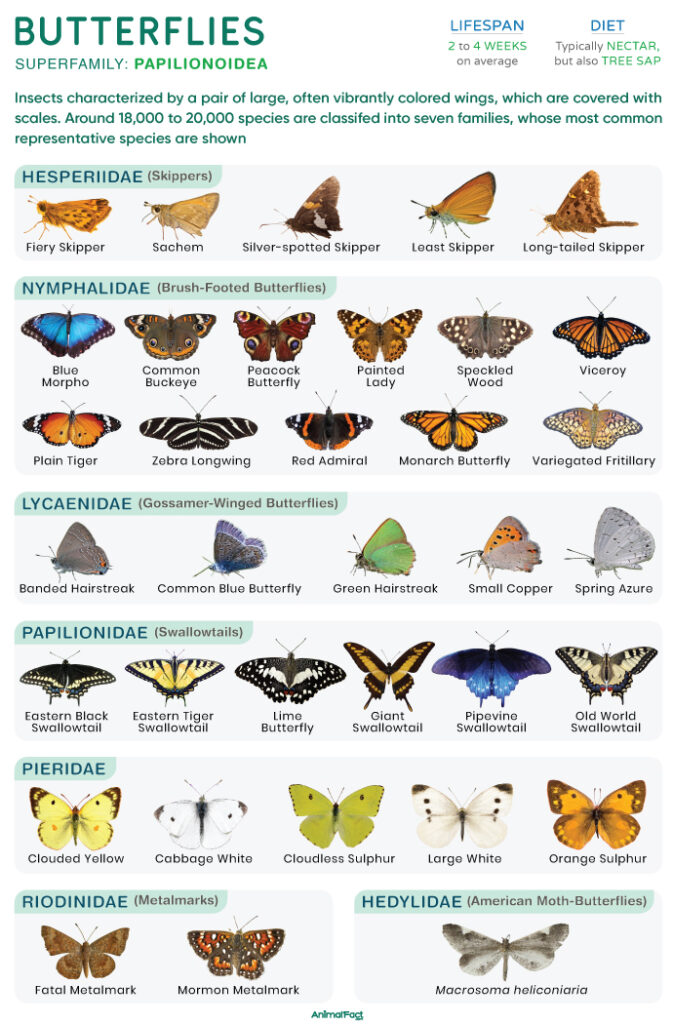

Butterflies are insects characterized by a pair of large, often vibrantly colored wings, which are covered with scales. They belong to the superfamily Papilionoidea within the order Lepidoptera, which also includes moths. Around 18,000 to 20,000 species of butterflies are found worldwide (except in Antarctica).

They are holometabolous, undergoing a complete metamorphosis in which eggs develop into larval (caterpillar) and pupal stages before emerging as adults. The adults primarily feed on nectar from flowers using their straw-like mouthparts, and while doing so, they sometimes pick up pollen grains on their bodies, thereby helping in pollination.

Many butterflies rely on camouflage to blend with their surroundings, while others exhibit warning coloration to signal toxicity. Some even mimic unpalatable species to ward off their predators.

On average, most butterflies measure around 0.8 to 3 in (2 to 7.6 cm) in body length. The average wingspan is around 2 to 6 in (5 to 15 cm). However, females of the largest species, the Queen Alexandra’s birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae), have a wingspan of 10 to 11 in (25 to 28 cm).

One of the smallest species, the western pygmy blue (Brephidium exilis), has a wingspan of only 0.4 to 0.8 in (12 to 20 mm).

Butterflies have a bilaterally symmetrical body divided into three broad segments: head, thorax, and abdomen.

The head is equipped with a pair of segmented antennae, a pair of compound eyes (but several simple eyes in caterpillars), and specialized mouthparts. Unlike moths, which have tapering tips, the antennae of butterflies have clubbed tips with sensory receptors that detect odors.

Their mandibles are reduced in size or absent, whereas the first maxillae are elongated to form a tubular structure or proboscis that remains coiled at rest. When feeding, the butterfly extends its proboscis and sucks its meal from the food source. The first and the second maxillae bear small, finger-like projections called palps, which are sensory in function.

Like most insects, the compound eyes of butterflies are composed of thousands of tiny visual units called ommatidia. These structures provide them with an almost 360° field of vision, helping them detect objects and movements around them. However, their eyes cannot form sharp images of distant objects.

While humans have only three types of photoreceptor cells, butterflies may have as many as six (or more), enabling them to see ultraviolet, blue, green, red, and other wavelength ranges.[1]

The thorax is subdivided into the pro-, meso, and metathoracic regions, each bearing a pair of legs. The mesothorax and metathorax bear a pair of scaly forewings and hindwings, respectively, with the forewings being larger than the hindwings. When at rest, butterflies hold their wings vertically above their bodies, unlike moths, which rest with their wings spread flat or folded over their bodies. Moreover, unlike moths, the forewings and hindwings of butterflies are not hooked together; instead, they function through friction between their overlapping parts.

The rearmost section of the body, the abdominal region, is elongated and bears 10 segments. It contains most of the internal organs, including the digestive, excretory, and reproductive systems. The first eight segments of the abdomen also possess tiny openings or spiracles that aid in respiration.

The terminal segments of the abdomen bear the reproductive organs. In males, the tip of the abdomen bears a pair of claspers that hold the female securely during copulation, along with a copulatory organ called the aedeagus, which transfers sperm to the female. In females, the tip of the abdomen is equipped with an ovipositor for laying eggs, as well as a specialized sac known as the spermatheca, where sperm received from the male is stored.

The body color of butterflies ranges from dull browns and blacks to bright metallic shades. It is the pigments on the scales of their wings that make them so visually striking.

While melanins produce blacks and browns, uric acid derivatives and flavones impart yellow shades to the scales. Blues, greens, reds, and iridescent shades arise from microscopic structures on the wing scales (structural coloration), which reflect, scatter, and interfere with light to create vivid colors. Butterflies such as Heliconius, Junonia, and Morpho provide striking examples of this effect.[2][3]

All species are classified into the following 7 families.

A recent molecular study (2023) states that butterflies originated Cretaceous Period (around 101 million years ago), but they started to diversify around 90 million years ago. The earliest butterfly fossil as yet, Protocoeliades kristenseni, which is about 55 million years old, was unearthed from the Fur Formation of Denmark.

According to The Lepidopterists’ Society, of all butterfly species, around 775 are Nearctic, 7,700 are Neotropical, 1,575 are Palearctic, 3,650 are Afrotropical, and about 4,800 occur across the Oceanian regions.[4]

The monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), one of the most widespread species, is native to the Americas but is thought to have spread globally by the 19th century (or earlier). Today, it is also found in Australia, New Zealand, other parts of Oceania, and even the Iberian Peninsula.

These insects are particularly abundant in tropical and subtropical regions, where plant diversity is highest. They prefer living in areas where flowers (for nectar) and host plants (for larval growth) are abundant.

With a long, straw-like proboscis, adult butterflies primarily feed on liquid matter, especially nectar from flowers. However, when nectar is scarce, they feed on tree sap. Occasionally, butterflies may also feed on fluid from rotting fruit and decaying flesh, as well as blood (though such instances are rare).

Males of some butterflies, such as members of the family Nymphalidae, sip up water from mud, dung, and carrion, which are rich in sodium and sometimes amino acids (puddling). It is hypothesized that males collect the sodium and later transfer it to the females through the spermatophore as a nuptial gift.[5]

Some species, such as the Julia butterfly (Dryas iulia), have been observed feeding on the tears (lachryphagy) of turtles, crocodiles, and caimans.[6] Moreover, a few species of the genus Halpe have been found to land on humans to drink sweat.[7]

Most caterpillars are herbivorous, feeding on leaves of their host plants. However, some species are exceptions. For instance, larvae of the apefly (Spalgis epius) consume scale insects, whereas those of the moth butterfly (Liphyra brassolis) eat ant larvae.[8][9]

In contrast to moths, most butterflies are diurnal, foraging during the daytime. They sense their surroundings using the chemoreceptors located on the tips of their antennae.

To navigate, butterflies use the sun as a compass, adjusting their internal body clock accordingly. In cloudy conditions, they rely on the polarised light pattern in the sky.

During flight, butterflies flap their wings in a figure-eight motion, generating low air pressure above the wings and high pressure below them, resulting in lift. They tend to fly in a fluttery, zig-zagging pattern, a behavior that makes it difficult for predators to catch them.

Many species, such as the monarch butterfly and the painted lady (Vanessa cardui), are capable of migrating long distances over several generations. For instance, the eastern North American population of monarchs has been observed traveling thousands of miles south-west to overwintering sites in Mexico.

The painted lady undergoes the longest butterfly migration in the world. It undertakes a round trip of about 9,000 miles (14,484 km), stretching from tropical Africa to northern Europe and even the Arctic Circle. Up to six successive generations of these butterflies complete this entire journey.[10]

Although lifespan varies among species, butterflies live for 2 to 4 weeks on average.[11] The mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) has one of the longest lifespans among butterflies, surviving around a year.[12] In contrast, the lime butterfly (Papilio demoleus) has an average lifespan of only about 5 days.[13]

To mate, male butterflies court their female counterparts through various strategies. While some males display their brightly colored wings to attract the females, others may release pheromones to draw them closer. Once the female selects her mate, the pair lands on a leaf, stem, or ground. The male grasps the female and inserts his aedeagus into her genital opening, transferring a spermatophore (packet of sperm) that the female stores in her spermatheca for fertilizing her eggs later. Males of some butterflies, such as the Apollos (Parnassius), plug the genital openings of the females to prevent them from mating again.[14]

Most females lay between 100 and 300 tiny eggs, over several days to weeks, typically on plants, with each species having a specific host plant range. Depending on the species, eggs are laid singly or in clusters. As the female lays her eggs, the ovipositor produces a sticky, glue-like substance that hardens quickly, helping attach the eggs to the leaves. These pale-colored eggs, typically around 1 to 3 mm in diameter, are covered by a hard shell or chorion.

The eggs typically hatch into larvae (caterpillars) in 3 to 8 days. The larvae, distinguished by their short antennae, strong mandibles, and paired maxillae, usually feed on the leaves of their host plants. They also have a small tube-like structure on the labium called a spinneret, which produces silk to anchor them securely to leaves. Besides having true thoracic legs, caterpillars possess up to six pairs of prolegs arising from the abdominal segments.

Most caterpillars undergo 4 to 5 molts in total, shedding their old exoskeleton at the end of each instar under the influence of a series of neurohormones. When the caterpillar is fully mature, it produces hormones such as prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH). Under the influence of these hormones, the larva stops feeding and starts to seek a suitable pupation site, typically the underside of a leaf. After finding a proper site, it spins a silk button and fastens itself to the surface using it, molting one final time to form a pupa. The pupae are naked (known as chrysalis) and usually hang head-down using the cremaster hook (a spiny structure at the tip of the abdomen). They may also suspend themselves head-up with a silk girdle around the body.

Most of the larval tissues break down inside the pupal body, and the resulting materials are reused to form the adult or imago. During this process, the wings and proboscis develop fully. When ready, the pupa splits open its case and pumps hemolymph into the wing veins, causing the wings to expand and harden within a few hours. The pupa-to-adult transformation typically takes one to two weeks to complete.

Adult butterflies are preyed upon by birds (such as flycatchers, swallows, sparrows, and others), lizards, frogs, and other insects, including praying mantises, dragonflies, and robber flies. They also get trapped in spider webs and are eventually eaten by them.

Ants, wasps, beetles, and true bugs feed on butterfly eggs and caterpillars. Some parasitoid wasps, such as braconids, lay their eggs inside butterfly eggs or caterpillars. Once the wasp larvae hatch, they feed on the host from within.[15]