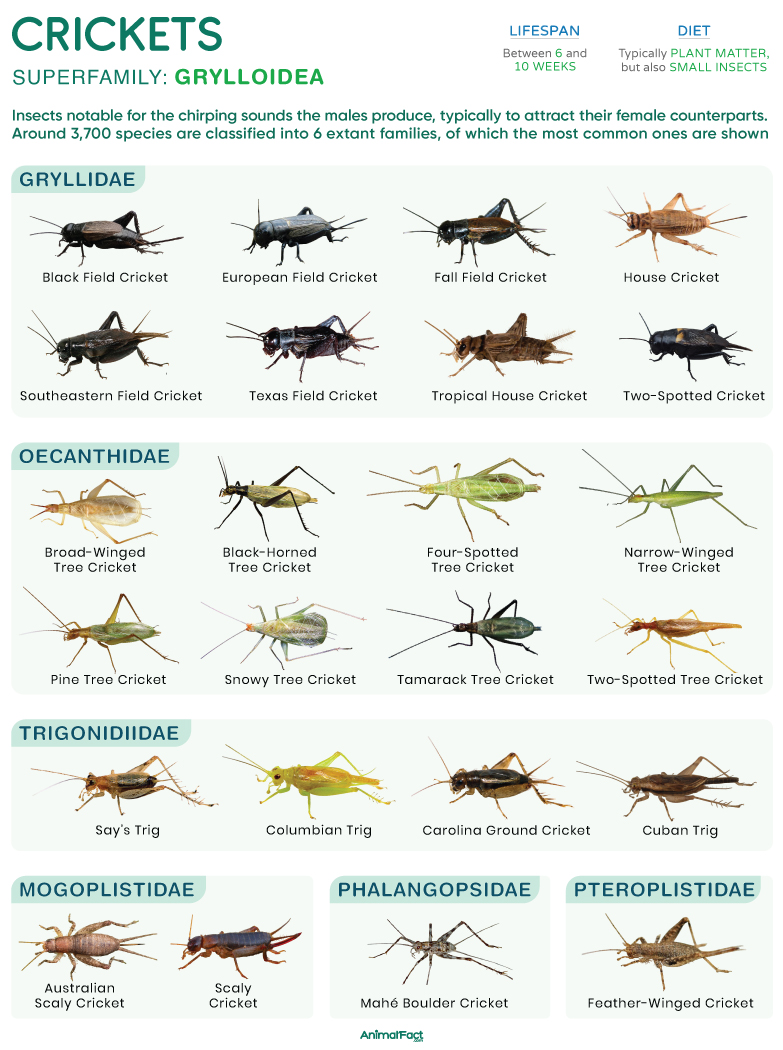

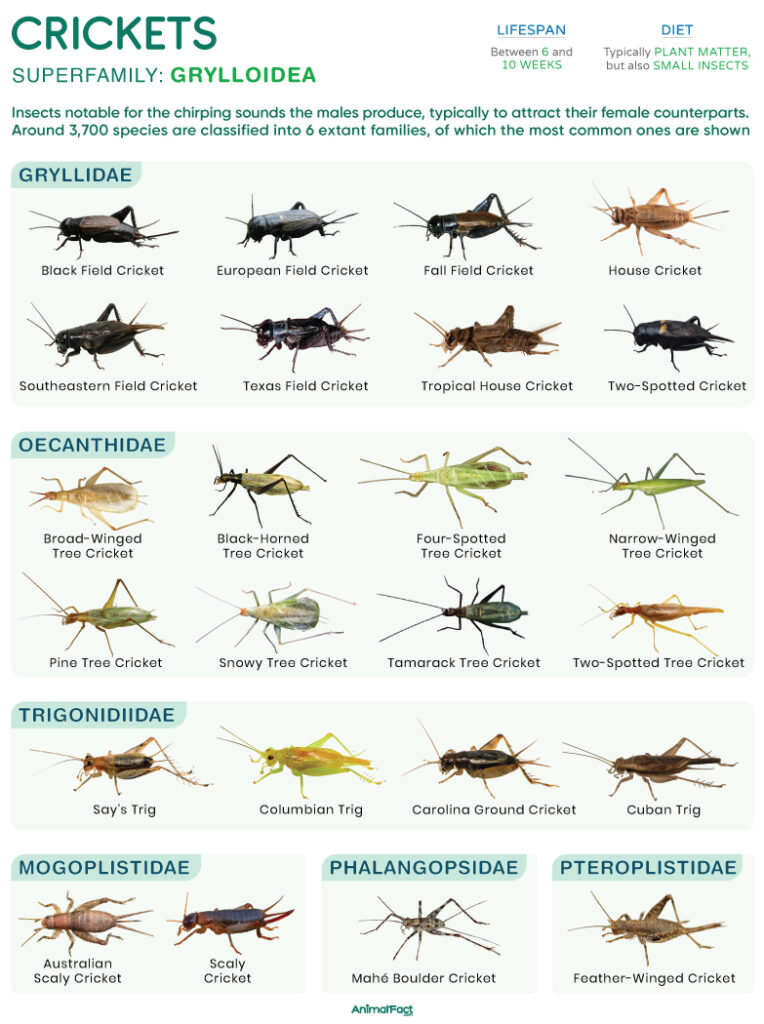

Crickets are primarily nocturnal insects that constitute the superfamily Grylloidea. Closely related to katydids and grasshoppers, these insects are notable for the chirping sounds the males produce (stridulation), typically to attract their female counterparts for mating. They emit these sounds by rubbing their forewings, which bear specialized stridulating organs. Owing to their enlarged hind legs, these insects are also good at jumping.

There are around 3,700 known species of crickets, with the highest diversity in the tropics. They occupy various habitats, ranging from forest canopies and grasslands to caves and leaf litter. Although generally harmless to humans, crickets are often considered a nuisance because of their incessant chirping at night. Some species may also cause damage to crops, as well as clothing, paper, or stored food.

These insects vary in length from 0.12 to 2 in (3 to 50 mm). One of the smallest crickets, Myrmecophilus acervorum, measures around 0.14 in (3.5 mm), whereas members of the genus Brachytrupes are the largest, measuring around 2 in (50 mm).[1]

Like other insects, crickets have cylindrically shaped bodies divided into three main segments: head, thorax, and abdomen. As with all arthropods, these insects are encased in a tough, chitinous exoskeleton.

They typically appear in muted shades of brown, grey, and green, which help them merge seamlessly with their surroundings.

The head is spherical, bearing a pair of long, slender antennae (unlike grasshoppers with short antennae) that stem from cone-shaped segments called scapes. There are a pair of compound eyes nestled behind these scapes. Additionally, there are three simple eyes (ocelli) on the forehead.

They possess chewing-type mouthparts, with strong, toothed mandibles adapted for cutting, crushing, and grinding food.

The middle region of the body, the thorax, is subdivided into the pro-, meso, and metathoracic segments. Each thoracic segment bears one pair of legs. The third pair of legs is particularly enlarged for jumping. The auditory organs (tympana) are located on the front legs.

The prothorax is covered dorsally by a highly sclerotized, trapezoidal, shield-like plate called the pronotum, which is primarily protective in function.

The mesothorax and the metathorax bear the chitinous forewings (tegmen) and the hindwings. While the forewings are thickened, leathery, and protective, the hindwings are broad, membranous, and used for flight.

In males, the forewings are specialized for stridulation. On each forewing, a large vein with serrated edges forms a file, while a hardened ridge, a scraper, is located near the rear edge of the opposite forewing.

At rest, the wings lie flat on the body, with the hindwings folding like a fan under the forewings. However, some species, such as ground crickets (subfamily Nemobiinae), are completely wingless.

In most species, the abdominal region is divided into 11 visible segments. At the tip of the last segment are a pair of sensory appendages called cerci. The females, in particular, possess a long, tubular ovipositor organ that helps in egg-laying.

The abdomen also bears the respiratory openings (spiracles), as well as the digestive and excretory organs.

The superfamily Grylloidea comprises about 3,700 known species classified into 6 extant families.

Two families, Gryllotalpidae (mole crickets) and Myrmecophilidae (ant crickets), were initially placed under the superfamily Grylloidea, but they have now been classified under a new superfamily, Gryllotalpoidea.

Several cricket-like insects from families outside Grylloidea are also commonly referred to as ‘crickets.’ For example, bush crickets or katydids (family Tettigoniidae), Jerusalem crickets (family Stenopelmatidae), and camel or cave crickets (family Rhaphidophoridae) all have the word ‘cricket’ in their names.

Crickets are found in all parts of the world except at latitudes higher than about 55° North and South. They are particularly diverse in the tropical region, especially in Malaysia, where around 90 species were heard chirping from a single location near Kuala Lumpur.[2]

These insects occupy a wide range of habitats, including upper tree canopies, bushes, grasses, and herbs. While some are adapted to live in caves, others, such as mole crickets (family Gryllotalpidae), are subterranean, occupying underground burrows in moist soil.

Some species, such as Apteronemobius asahinai, inhabit areas near water, particularly the mangrove forest floors that witness regular tidal flooding.[3]

These insects typically feed on plant matter, including leaves, flowers, stems, fruits, and seeds. However, they are omnivorous and may supplement their diet with smaller insects (as well as their larvae and eggs) and spiders.

Most crickets are nocturnal, spending most of the daytime hiding in cracks, under stones or fallen logs, in leaf litter, or in the cracks on the ground.

Most male crickets produce a loud chirping sound through a repetitive scraping motion (stridulation). They rhythmically raise and lower the forewings so that the scraper of one wing rasps against the file of the other wing. The vibrations travel across the wings, where a specialized area of sclerotized membrane, the harp, amplifies the volume of sound.

They typically chirp to attract females, but they may use different chirp patterns for territorial defense or aggression toward rival males.

For most species, the chirp rate increases with rising temperatures. For instance, Oecanthus capensis chirps at about 86 chirps per minute at 13°C, rising to around 195 chirps per minute at 20°C, and further to about 273 chirps per minute at 25°C.[4]

If camouflage is not enough, crickets adapt to other defense strategies. They may either try to flee from their predators or face them head-on. Although winged species do fly, their flight is only a clumsy scuttle to a nearby secure place.

Most crickets have poor biting capacity, though some members, such as raspy crickets (family Gryllacrididae), have been found to have one of the strongest bites among insects.[5]

Depending on the species, adult crickets typically live between 6 and 10 weeks. They can survive up to 2 weeks without food, but they will die in a few days without water.

Before mating, the male crickets try to attract females by producing chirping sounds through stridulation. Once a female is attracted, she mounts the male, and a single spermatophore (packet of sperm) gets transferred to her genital opening from the male. The sperm reaches the oviduct in a few minutes to an hour, depending on the species. After the eggs are fertilized, they are laid either in the soil or inside the stems of plants. Short-tailed crickets (Anurogryllus) excavate a burrow with chambers and lay their eggs in a pile on the chamber floor.[6]

In about two weeks, the eggs hatch into small, wingless nymphs (similar in size to a fruit fly). The nymphs undergo 8 to 10 molts, developing wing buds in the meantime. With each successive molt, they start to resemble the adults. In the final molt, the nymph leaves behind the exuvia, emerging as a fully winged adult.

These insects are preyed upon by a wide range of invertebrate and vertebrate predators. They fall prey to spiders, mantises, centipedes, and beetles, as well as frogs, lizards, and occasionally small, insectivorous snakes. Nocturnal birds such as owls and nightjars hunt crickets at night, while diurnal birds, like robins, sparrows, and starlings, feed on them during the day.

Some mammals, including shrews and hedgehogs, may feed on burrowing crickets. Being nocturnal, crickets are also targeted by bats.[7] A few rodents, such as mice, may opportunistically consume both adult crickets and their eggs.