Ants are a group of insects that constitute the family Formicidae within the order Hymenoptera, which also includes sawflies, bees, and wasps. They are easily recognized by their elbow-like antennae and a narrow, waist-like petiole connecting the thorax and the abdomen. These insects are ubiquitous, found almost everywhere except in Antarctica and some remote islands, such as Greenland, Iceland, and parts of Polynesia.

They exhibit eusociality, living in colonies that typically comprise distinct castes: queens (fertile females), drones (fertile males), and workers (sterile females) with specialized roles such as foraging, brood care, nest maintenance, and even defense. Depending on the species, these colonies can range from a few dozen to millions of individuals. They are holometabolous insects, which develop from an egg into an adult by passing through larval and pupal stages.

Although typically small in size, ants are surprisingly powerful, lifting objects 10 to 50 times their body weight. They also exhibit exceptional cooperative behavior, communicating through pheromones, touch, and sound.

Ants typically range from 0.030 to 2.0 in (0.75 to 52 mm) in length. However, the largest species is the fossil Titanomyrma giganteum, the queens of which were around 2.5 in (6 cm) long with a wingspan of 6 in (15 cm). Among living ants, one of the largest species is Dinoponera gigantea, with females ranging from 1.2 to 1.6 in (3 to 4 cm).

According to the Guinness World Records, the world’s smallest ants are those in the genus Carebara, particularly Carebara atomi and Carebara bruni, the workers of which are as small as 0.31 to 0.39 in (0.8 to 1.0 mm).

Like other insects, ants have a segmented body with three main sections: the head, the thorax (mesosoma), and the abdomen (metasoma). A hard exoskeleton encloses all the body segments of ants. Depending on the species, the exoskeleton of most ants is yellow to red or brown to black. However, some species, such as the green-head ant (Rhytidoponera metallica), have a distinct, greenish-purple metallic sheen.

The most distinguishing feature of an ant’s head is its pair of multi-segmented, elbowed (geniculate) antennae, with a distinct bend or joint between two main parts: the scape (the long first segment attached to the head) and the flagellum (the multi-segmented distal portion). The antennae are sensory and help these insects detect chemicals, air currents, and vibrations.

A pair of compound eyes aids in vision in reproductive individuals. Additionally, they also typically have three simple eyes or ocelli that help detect light intensity and direction. However, some ants, such as those in the genus Typhlomyrmex, are completely blind, including their reproductive individuals.[1]

A pair of strong mandibles helps manipulate food, build nests, and ward off predators.

The thoracic or mesosomal region in ants has three main segments: the prothorax, mesothorax, and metathorax, each bearing a pair of legs. Each leg ends in a hooked claw that helps the insect hook onto a substrate. Reproductive individuals bear two pairs of wings, one pair attached to the mesothorax and the other arising from the metathorax.

The metathorax ends in the propodeum, the first abdominal segment that remains fused with the thoracic region. The propodeum connects to the petiole, a narrow, waist-like segment that connects the thorax to the abdomen.

On the posterior sides of the mesosoma, just above the hind legs, lie specialized exocrine glands called metapleural glands. These glands, typically found in worker ants, produce antimicrobial secretions that help maintain colony hygiene.

Keeping aside the propodeum and petiole, the abdominal region comprises a bulbous rear part, the gaster, which typically begins with the 4th abdominal segment. The gaster bears the vital organs of the body, such as the digestive and reproductive organs.

Some ants, such as fire ants (Solenopsis), possess a sharp sting located at the tip of their gaster, which they use in defending themselves against their predators.[2] Others, like members of the subfamily Formicinae, lack stings but possess an acidopore through which they spray defensive chemicals such as formic acid.[3]

The name ant derives from ante of Middle English, whereas the word Formicidae stems from the Latin word formīca, which translates to ‘an ant.’

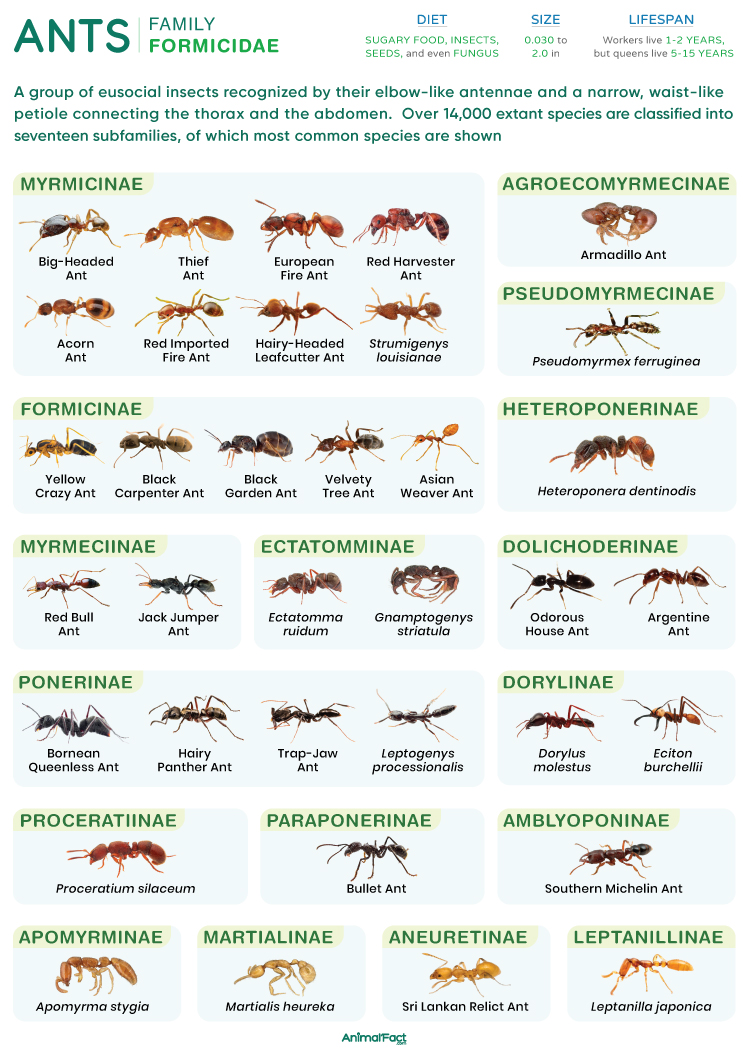

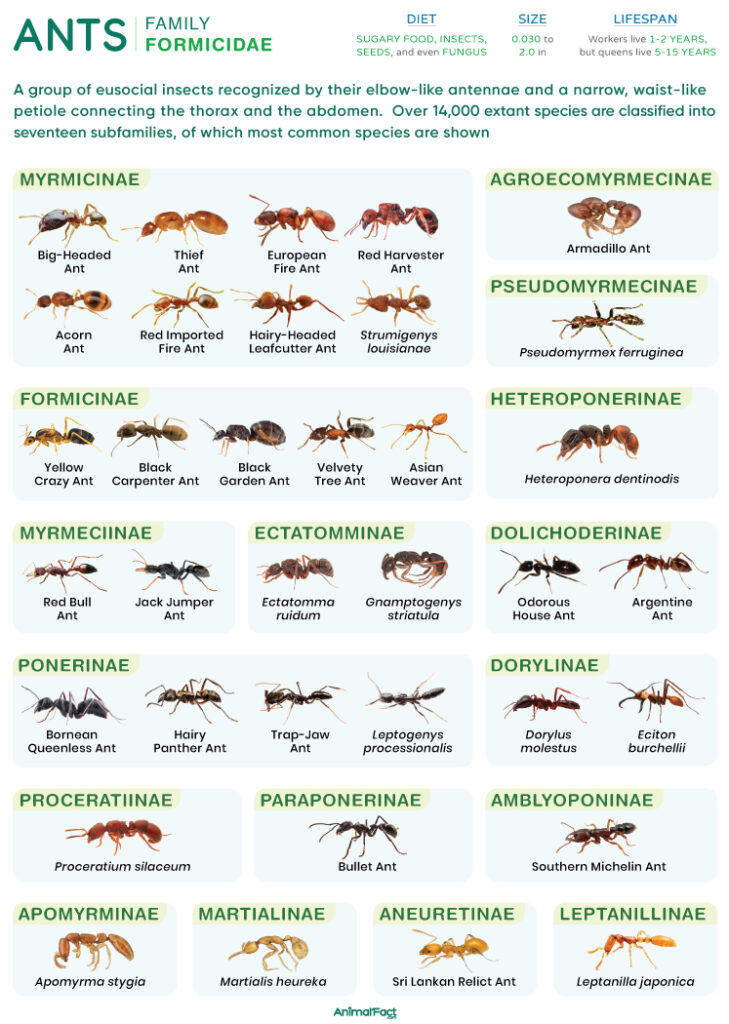

According to AntWeb, as of 2025, there are over 14,000 extant species of ants. A 2020 study on ant phylogeny classifies all species into 17 subfamilies.[4]

The oldest fossils of ants, belonging to the subfamilies Haidomyrmecinae, Sphecomyrminae, and Zigrasimeciinae, date back to the mid-Cretaceous Period (around 113 to 100 million years ago). Modern subfamilies started to appear towards the end of the Cretaceous Period (around 80 to 70 million years ago).

Ants are found on all continents except Antarctica. Moreover, a few remote islands, such as Greenland, Iceland, the Hawaiian Islands, and parts of Polynesia, also lack native ant species.

Africa has the highest number of ant species, with approximately 2,500 species documented. This is followed by the Neotropical region, comprising around 2,160 species, and Asia, with an estimated 2,080 species. Australia has a relatively lower diversity, with around 980 species. The Nearctic realm contains about 580 species, whereas Europe has only around 180 species.

Initially, global ant abundance estimates ranged from 1015 (1,000 trillion) to 1017 (100 quadrillion) individuals (according to myrmecologist E. O. Wilson), with corresponding biomass figures ranging broadly between 5 and 100 megatonnes of carbon (Mt C). However, a recent study by Schultheiss et al. revealed that there are around 2 × 1016 (20 quadrillion) ants on Earth, accounting for about 2.5 million ants for every living person. The total global ant biomass is estimated at 12.3 Mt C, which exceeds the combined biomass of all wild birds and mammals and equates to about 20 % of human biomass.[5]

These insects are the most abundant in tropical moist forests and tropical savannahs, followed by temperate forests. Although most ants are terrestrial, a few species are adapted to aquatic or semi-aquatic environments. For instance, Polyrhachis sokolova builds nests in mud, sealing them with air pockets when tides rise.[6]

Most ants are omnivorous generalists, feeding on both plant and animal matter that they come across. They also scavenge on other insects, spiders, and other invertebrates. Some species, such as the odorous house ant (Tapinoma sessile), typically feed on honeydew, as well as nectar and other sugary food.[7]

Some leafcutter ants, such as Atta and Acromyrmex, feed exclusively on fungus that they cultivate in their colonies.[8]

These insects are active throughout the year in the tropics. However, some species in colder regions enter a state of inactivity or hibernation during winter.

Ants live in colonies, constituting individuals that develop into morphologically and behaviorally distinct castes. The following major castes are found in the colonies of most ant species.

In a few primitive ant groups, such as Diacamma, the colony lacks queens. Instead, they have reproductive worker ants known as gamergates that function as queens within colonies.[9] In others, such as honeypot ants, some selected workers (called repletes) are fed until their gasters are distended, serving as living food storage vessels.

Since most ants (except reproductive individuals) lack wings, their primary mode of locomotion is walking. A few species, such as Jerdon’s jumping ant (Harpegnathos saltator), can jump by synchronizing the movements of their middle and hind legs.

Some fire ants have been documented to form chains or rafts to bridge gaps over water. These rafts may involve thousands to over 100,000 ants, depending on the colony size and environmental conditions.[10]

Workers may travel up to 700 ft (200 m) from their nest to forage. They sense directions based on the position of the sun. Some desert ants (Cataglyphis) navigate long distances using an internal step-counting mechanism (like a pedometer). These ants may also use optical flow by observing how objects in their surroundings move past them as they walk around.

While foraging, ants leave a trail of pheromones that their nestmates detect using their antennae, allowing them to follow the path to a food source. Similarly, when threatened, workers release alarm pheromones to trigger aggressive defense responses in the colony.

Some ants, such as Formica, release ‘propaganda pheromones’ when invading another colony. These pheromones cause host ants to misidentify their own nestmates as threats, creating confusion in the invaded colony.[11]

Ants exhibit a wide range of chemical, mechanical, and behavioral defenses to protect themselves and their colony members.

Depending on the species, ants build their nests subterraneanly, arboreally, or in microhabitats such as hollow stems, logs, under stones, or even acorns. They typically use soil and plant matter to build these nests.

Some ants, such as the Eciton burchellii, interlock their bodies to form temporary, mobile nests called bivouacs. In contrast, weaver ants (Oecophylla) build treetop nests by first pulling leaves together using chains of workers and then using their silk-producing larvae to glue the leaves together.

The lifespan of ants varies with species and the caste. For instance, carpenter ant (Camponotus) workers may live up to 5 years, whereas red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) workers typically survive only about 60 days.[13]

Queen ants, on the other hand, live much longer, typically surviving between 5 and 15 years. According to the Animal Ageing and Longevity Database, black garden ant (Lasius niger) queens have been documented to live for a maximum of 28 years in captivity.

Most ant species are univoltine, producing one generation every year. Typically, during the late spring or early summer, in hot and humid conditions, winged females and males (alates) take their nuptial flight. The male usually takes flight before the female, later drawing her to a common mating ground using visual cues.

Having mated, the female seeks a suitable substrate to start the colony. It settles on the substrate, breaks its wings off using its tibial spurs, and begins laying eggs. The female can selectively fertilize her future eggs with the sperm stored in her spermatheca. Fertilized eggs give rise to diploid females, whereas unfertilized eggs form haploid males (haplodiploid sex determination).

As holometabolous insects, ant eggs go through larval and pupal stages before becoming adults. The workers feed the larvae mouth-to-mouth by regurgitating liquid food from their crop (trophallaxis). Around early to mid-larval instars, caste determination occurs, driven by nutrition, hormones, and colony cues. The larvae then typically undergo a series of four or five molts to become pupae.

The pupae of some species, such as those in the genus Formica, are enclosed in a silken cocoon, whereas in others they are naked. The appendages of the pupae are not fused to the body, unlike those in butterfly pupae. Once fully developed, the adult ant emerges from the pupa.

The first adults to hatch are the workers, often referred to as nanitics. They are small and weak, functioning as the earliest builders of the colony. They begin to serve the colony, foraging for food and nursing the unhatched eggs.

A few species, such as Cataglyphis cursor, exhibit thelytokous parthenogenesis, where queens produce diploid daughters from unfertilized eggs.[14]

Ants face predation from a wide range of animals. They are preyed upon by lizards, frogs, toads, and caecilians. Among birds, antbirds, woodpeckers, and flickers feed on adult ants and their larvae. Mammals, such as anteaters, pangolins, echidnas, and aardvarks, feed on ants.

Among invertebrates, some spiders, like those of the family Zodariidae, prey on ants. Some beetles and assassin bugs also consume them.