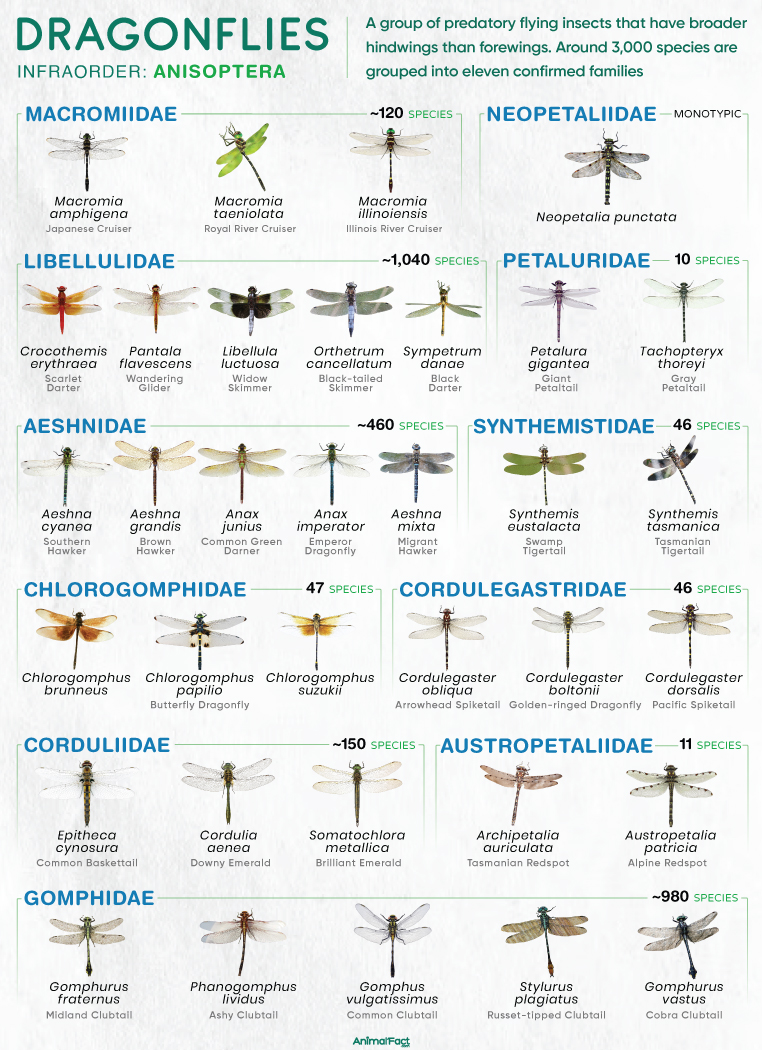

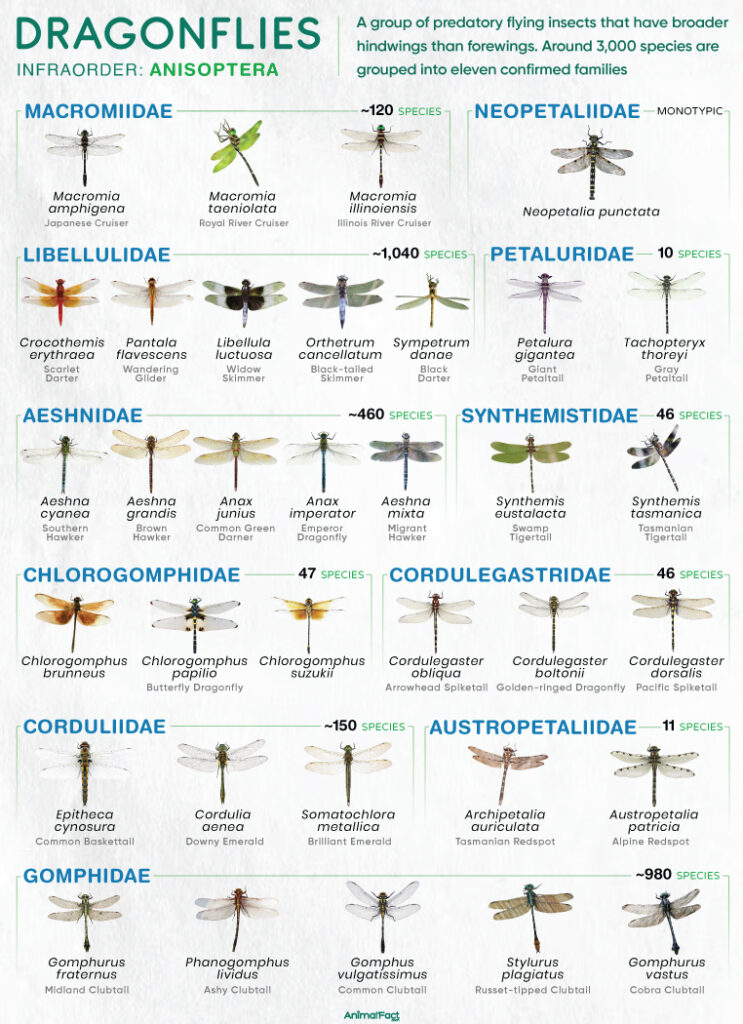

Dragonflies are predatory, flying insects that belong to the suborder Anisoptera within the order Odonata. The suborder derives its name from the Greek words anisos (unequal) and pteron (wing) since the hindwings of dragonflies are broader than the forewings.

Adults are characterized by an elongated abdomen and a pair of large compound eyes that provide an almost 360° vision. These insects are often mistaken for damselflies (suborder Zygoptera), which are phylogenetically close but lighter in build. Moreover, while damselflies hold their wings folded at rest, dragonflies hold their wings flat and away from their bodies.

Being almost cosmopolitan in distribution, dragonflies are found on all continents except Antarctica. They are hemimetabolous, developing from an egg to an adult through multiple nymphal stages. Most of their life is spent as aquatic nymphs, emerging as adults, typically for a few weeks only to mate and reproduce.

On average, most dragonflies range between 1 and 4 in (2.5 and 10 cm) in body length and 2 and 5 in (5 and 12.5 cm) in wingspan.

The largest living dragonfly, the giant hawker (Tetracanthagyna plagiata), has a maximum wingspan of about 6.42 in (163 mm). In contrast, the smallest, the scarlet dwarf (Nannophya pygmaea), has a wingspan of only 20 mm (0.8 in).

As insects, dragonflies have three body segments: the head, thorax, and abdomen. Their bodies are covered by an exoskeleton comprising hard, chitinous plates joined by flexible membranes.

The head is large and prominent, with relatively short antennae. This body part is largely made up of a pair of compound eyes, each consisting of numerous ommatidia. The number and size of the ommatidia vary with species. For instance, the variable darner (Aeshna interrupta) has about 22650 ommatidia of two varying sizes, while the giant dragonfly (Petalura gigantea) has around 23890 ommatidia of just one size. In addition to the compound eyes, these insects also have three simple eyes (ocelli).

The mouthparts are well-adapted for biting and chewing, having a flap-like upper lip (labrum), which they rapidly shoot forward to capture prey.

The thorax consists of the pro-, meso, and metathorax. The prothorax is flattened dorsally into a shield-like disc having two transverse ridges. The meso- and metathorax are fused into a rigid, box-like structure that provides the attachment points for two pairs of wings and three pairs of legs.

The hindwings are broader than the forewings, each wing comprising numerous veins that carry hemolymph. In most large species of dragonflies, the females have shorter and wider wings than males. They hold their wings horizontally both in flight and at rest.

The legs, rarely used for walking, assist in perching on a substrate and holding prey. Each leg comprises two short basal joints, two long joints, and a three-jointed foot. The feet are equipped with claws, ensuring a better grip.

The long leg joint bears rows of spines. Some male dragonflies use a particular row of spines on each front leg to help clean the surface of their compound eyes.

The ten-segmented abdomen is long and slender, with the tenth segment bearing three terminal appendages: two superiors (cerci or claspers) and one inferior appendage (epiproct or paraproct). In females, these appendages are typically shorter, less prominent, and may be vestigial in some species.

In males, the second and third segments are enlarged, with the underside of the second segment having a cleft that forms the secondary genitalia. The secondary genitalia comprises the lamina, hamule, genital lobe, and penis. The primary genital opening is on the ninth segment.

In females, the eighth segment contains the genital opening on the underside. The opening is covered by a simple flap (vulvar lamina) or bears a tube-like ovipositor, depending on the species.

Many species of dragonflies are vividly colored in combinations of yellow, red, brown, and black pigments. Some display iridescent or metallic colors caused by microstructures in the cuticle that reflect blue light. Others, like the green darner (Anax junius), exhibit a non-iridescent blue produced by light reflecting off tiny spheres within the endoplasmic reticulum.[1]

Around 3,000 species of dragonflies are classified into 348 genera in 11 confirmed families and a single uncertain group, incertae sedis.

Dragonflies are found on every continent except Antarctica. Most species are tropical, with very few found in temperate regions. Unlike damselflies, which have fairly restricted distributions, some dragonfly species are spread across continents. For instance, the globe skimmer (Pantala flavescens), the most widespread of all species, is almost cosmopolitan, found in the warmer regions of most continents.

These flies inhabit a wide range of elevations, from sea level up to mountainous regions, with the number of species declining at higher altitudes. Their highest recorded occurrence is of a species in the genus Aeshna in the Pamirs at about 3,700 m.[2]

Members of the families Libellulidae and Aeshnidae inhabit desert pools of the Mojave Desert, where temperatures range between 64°F and 113°F (18°C and 45°C).[3]

Adult dragonflies are almost exclusively carnivorous, primarily feeding on flying insects such as mosquitoes, flies, midges, moths, butterflies, bees, wasps, and even other dragonflies. However, when their preferred prey is scarce, they may consume aphids, termites, ants, and beetles.

Nymphs typically prey on most living things smaller than themselves. They consume aquatic insect larvae, water fleas, aquatic oligochaetes, tadpoles, and newly hatched fish. However, nymphs of certain species have been observed feeding on prey outside the water. For example, the sombre goldenring (Cordulegaster bidentata) nymph has been found hunting small arthropods on the ground at night. Though rare, nymphs from some Anax species have been reported feeding on fully grown tree frogs, such as Scinax cabralensis.[4]

These insects hunt while flying rather than landing to catch the prey. They subdue their prey by biting its head and carry it to a perch, where they remove the prey’s legs and consume it, typically head-first.

Dragonflies typically consume up to 95% of the prey they chase.[5] In a single day, a dragonfly may eat an amount of prey equal to about one-fifth of its body weight.

Dragonflies are agile fliers capable of switching directions as they wish. They can move in six different directions: upward, downward, forward, backward, and to the left and right. Unlike most insects, whose flight muscles are not directly attached to the wings, dragonflies have muscles that attach directly to the wing bases. This adaptation enables them to control each wing independently.

They have four different styles of flight, switching between each from time to time.

Some dragonfly species are migratory. For instance, the globe skimmer undertakes an annual journey, with each individual traveling over 6,000 km (3,730 miles), one of the longest known migrations among insects.[6]

Many male dragonflies, especially those in the families Libellulidae and Gomphidae, are highly territorial, often fiercely defending their territories against rivals of their own species, other dragonflies, and even different insects.

While males of some species, such as the common whitetail (Plathemis lydia), hold their abdomen aloft like a flag and dash toward their rivals, others engage in aerial fights and speedy chases.

Adults typically live for a week or two, but some species, such as the Emperor dragonfly (Anax imperator), survive for 6 to 8 weeks under ideal environmental conditions.

Depending on the species, nymphs can survive for several months to up to 5 years[7].

At first, male dragonflies select a suitable breeding site, where females are more likely to lay eggs. They then signal to the females to attract them, constantly trying to fend off rival males. When a male is ready to mate, he transfers a packet of sperm from his primary genital opening to the secondary genitalia in the second segment of the abdomen. He then grasps the female by her head using his claspers, forming a stable pair. This pair then flies in tandem, the male in the front, and perches on a twig or stem. Once settled, the female curls her abdomen and reaches the male’s genitalia to pick up the sperm, while the male holds the female’s head using his claspers (the heart or wheel posture). Even after the female has collected the sperm, the pair continues to fly in tandem, with the male guarding the female to ensure his sperm fertilizes the eggs. Additionally, the male even uses his penis and associated genital structures to scrape out sperm from previous matings.

In a few species, such as the common green darner (Anax junius), as the female prepares to lay her eggs, the male remains clasped to her, often staying attached even as she submerges herself to deposit the eggs.[8]

Females of the families Aeshnidae and Petaluridae possess a sharp-edged ovipositor, which they use to slit the stem or leaf of a plant on or near water, depositing their eggs inside. In contrast, females of the families Gomphidae, Corduliidae, Libellulidae, and Macromiidae tap the water surface repeatedly with their abdomen, gradually releasing their eggs.

Dragonflies are hemimetabolous, meaning they undergo incomplete metamorphosis, in which the egg develops into an adult through nymphal stages instead of a pupal stage. Depending on the species, a single clutch can contain up to 1,500 eggs, which typically hatch into aquatic nymphs, or naiads, in about a week. The nymphs extend their hinged labium to capture prey. They also breathe through gills in their rectum and propel themselves forward by expelling water through the anus.

The nymph undergoes between 6 and 15 molts, depending on the species, before it is ready to metamorphose into an adult. At this stage, it stops feeding and approaches the water surface. Once at the surface, the nymph remains still with its head out of the water, slowly adapting to breathing air.

Ready to take the final molt, the nymph crawls to a nearby plant, anchors itself, and starts to shed its exoskeleton (ecdysis). The adult dragonfly slowly emerges from its older coat, the exuvia. It arches backward, releasing all the abdominal segments from the coat, and plumps out its body by swallowing air. Hemolymph gushes into its wings, causing them to expand completely.

Despite being expert fliers, dragonflies become targets of some predators. Adults are preyed upon by falcons, such as the American kestrel, the merlin, and the hobby. During seasonal overlap in migration, Amur falcons may opportunistically prey on globe skimmers.[9] Some other birds, including nighthawks, swifts, flycatchers, and swallows, may also eat adult dragonflies. Ducks, herons, newts, frogs, fish, and water spiders consume nymphs.

Dragonflies are parasitized by water mites, gregarines, and flukes.