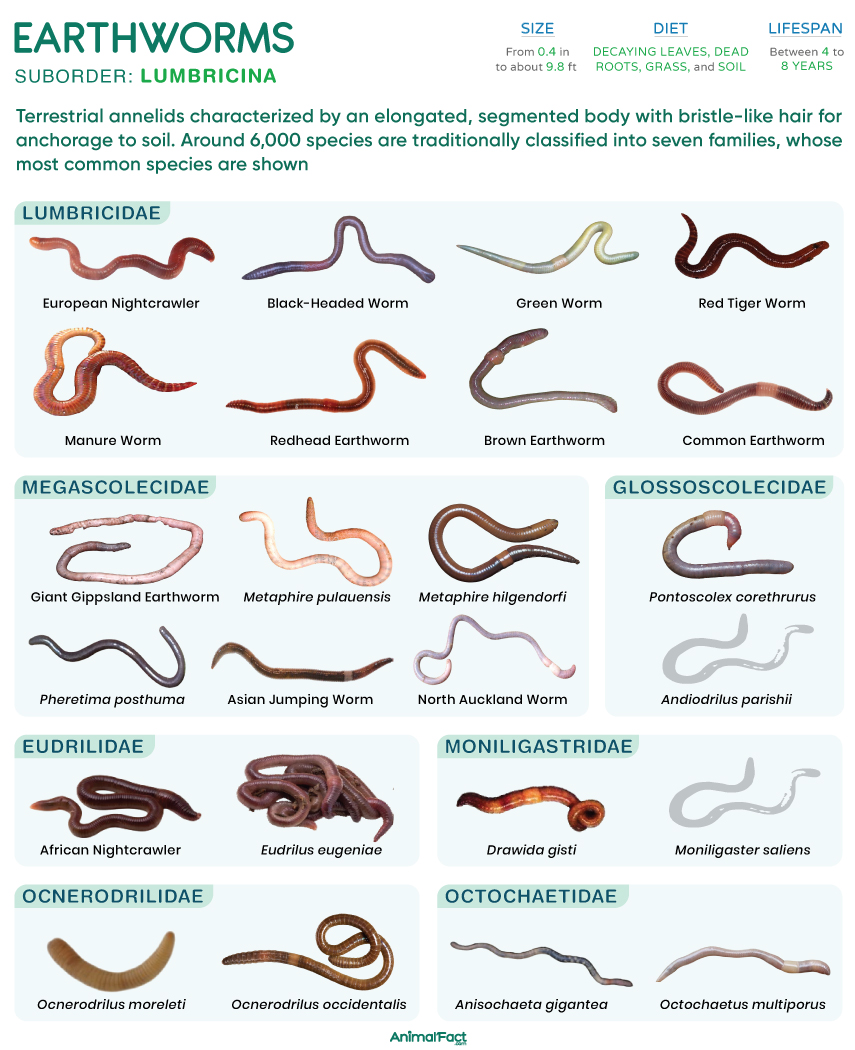

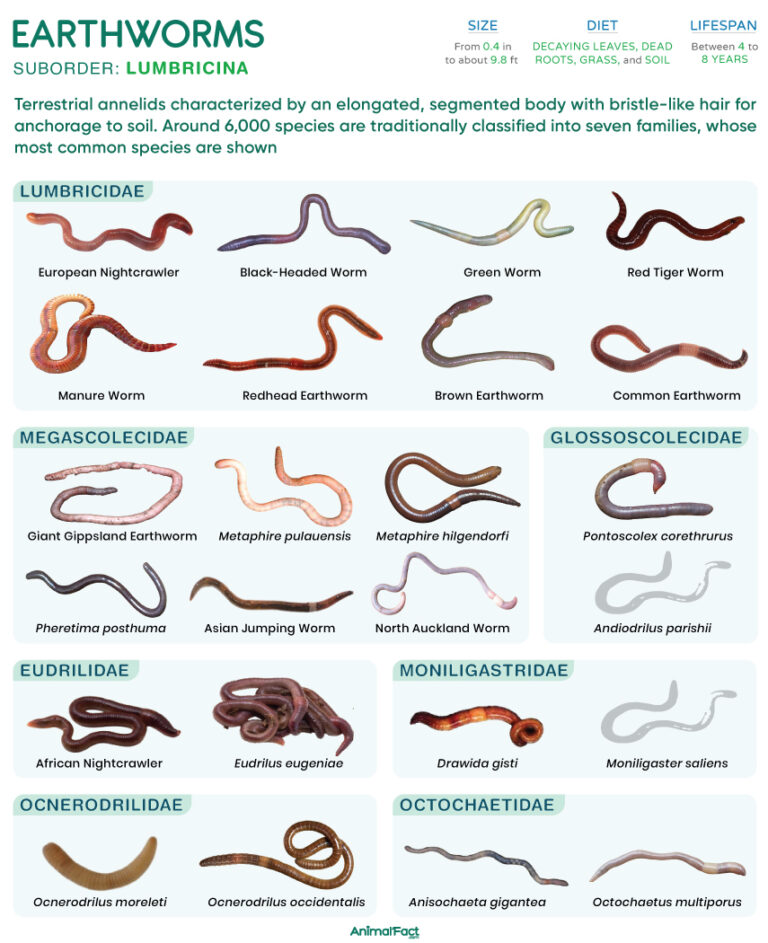

Earthworms are a group of terrestrial annelids that constitute the suborder Lumbricina. They are characterized by an elongated, segmented body equipped with bristle-like hair for anchoring to soil. These animals have a nearly cosmopolitan distribution, found on all continents except Antarctica.

The majority of species are burrowers, forming horizontal or vertical galleries within the soil, thereby contributing significantly to its aeration and structural mixing. Moreover, they are detritivores that feed on decaying plant and animal matter, thereby facilitating nutrient recycling and enhancing overall soil fertility.

These annelids vary considerably in size, ranging from just 0.4 in (10 mm) to about 9.8 ft (3 m) in length, depending on the species. Guinness World Records notes that the largest recorded specimen, an African giant earthworm (Microchaetus rappi), reached around 21 ft (6.7 m) in length and 0.8 in (20 mm) in diameter.[1] In contrast, smaller species, such as the New Zealand earthworm (Octochaetus multiporus), grow to around 12 in (300 mm) in length and 0.4 in (10 mm) in diameter.[2]

They have a tubular, elongated body that is typically divided into 100 to 200 ring-like segments called metameres. Some species, such as Lumbricus terrestris, bear as many as 150 segments. These segments are separated from each other by perforated transverse walls called septa.

The first segment, the head, bears the mouth and a fleshy, prehensile lobe called the prostomium, which seals the mouth when the worm is at rest. The most terminal segment, the periproct, bears a slit-like vertical anus.

In mature individuals, a thickened, glandular, saddle-like band called the clitellum appears between segments 14 and 32, depending on the species. This band secretes a cocoon in which eggs and sperm are deposited, allowing fertilization to take place. Additionally, the clitellar glands produce mucous that helps earthworms adhere to each other during copulation.

Each segment of the body (except the head and the anal segment) bears bristle-like lateral hair called setae, which help anchor parts of the body during movement. The number of bristles varies with species. For instance, the most common earthworms, like Lumbricus terrestris, bear eight setae per segment, whereas other species, such as the Asian jumping worm (Amynthas agrestis), have more than eight setae arranged in a circular pattern around each segment.

Earthworms have a closed circulatory system, in which blood circulates throughout the body via vessels. The blood that circulates is red in color due to the pigment hemoglobin dissolved in the plasma.

They have five main blood vessels: the dorsal vessel, the ventral vessel, the subneural vessel, and two lateroneural vessels. Segments 7 to 11 bear five pairs of muscular aortic arches (also known as lateral hearts), which pump blood from the dorsal vessel to the ventral vessel.

They do not possess specialized respiratory organs such as tracheae, lungs, or gills. Thus, gaseous exchange takes place through their moist skin (cutaneous respiration).

The blood capillaries carry absorbed oxygen to the body tissues and bring carbon dioxide back to the skin for release.

A straight gut runs along the length of the earthworm’s body, from the mouth to the anus. The gut is differentiated into an alimentary canal and associated digestive glands.

The alimentary canal comprises the mouth, buccal cavity, pharynx, esophagus, crop, gizzard, and an uncoiled intestine.

The intestine bears a large mid-dorsal, tongue-like fold called the typhlosole, which helps increase the surface area for nutrient absorption.

Apart from producing a range of digestive enzymes, including pepsin, amylase, cellulase, and lipase, the intestine also secretes unique surfactant-like compounds called drilodefensins, which nullify the toxic effects of plant polyphenols.

Almost every segment of an earthworm’s body (except for the first three and the last) bears a pair of metanephridia. These are coiled tubular structures that remove nitrogenous waste (typically as ammonia but also as urea in dry conditions) from the coelomic fluid and blood.

There are three types of metanephridia: integumentary (from segment 3 onwards), septal (from segment 15 onwards), and pharyngeal (segments 4,5, and 6). Each metanephridium opens into the coelom through a funnel-like nephrostome and expels waste to the outside through a nephridiopore, located on the worm’s body wall.

In earthworms, the central and peripheral nervous systems enable sensory perception. The central nervous system comprises bilobed cerebral ganglia (which function as the brain), subpharyngeal ganglia, circumpharyngeal connectives, and a ventral nerve cord.

The cerebral ganglia are located dorsal to the alimentary canal in segment 3, while the two circumpharyngeal connectives run around the pharynx, connecting the cerebral ganglia to the ventral nerve cord. The ventral nerve cord begins at the subpharyngeal ganglia and runs along the length of the body on the ventral side.

The peripheral nervous system comprises the nerves arising from the ganglia of each segment to innervate the muscles, skin, and other organs. These nerves enable local reflexes, allowing each segment to contract or respond to touch independently.

These annelids lack eyes and instead rely on other sensory structures for perceiving their surroundings. For example, photoreceptor cells, known as light cells of Hess, are distributed throughout the epidermis, with the highest concentration in the prostomium and anterior segments. Additionally, numerous tactile organs that detect touch, vibrations, and temperature changes are found in the epidermis. Several chemoreceptors also line the buccal cavity (buccal receptors), serving gustatory and olfactory roles.

They are hermaphrodites, meaning a single individual bears both male and female reproductive organs, between segments 9 and 15. Segments 9 and 10 (depending on the species) bear one or more pairs of spermatheca, which receive and store sperm. Similarly, segments 10 and 11 possess one or two pairs of testes contained within sacs. Two to four pairs of seminal vesicles are found between segments 11 and 15. The 15th segment also bears the male reproductive pore, which serves as an outlet for sperm.

The ovaries and oviducts are present in segment 13, while the female reproductive pores are found on segment 14.

Although the exact classification of earthworms continues to be revised, all species are traditionally classified into the following 7 families.

In some classifications, all terrestrial, soil-burrowing clitellate annelids are regarded as earthworms, and by this definition, members of the order Moniligastrida are also included. However, traditional classifications treat the suborder Lumbricina under the order Opisthopora as ‘true earthworms.’

Found almost on all continents, these animals thrive in nutrient-rich soils that are moist yet well-aerated, with optimal temperatures ranging from 10 to 15.6 °C (50 to 60 °F).[3] They typically prefer neutral to slightly acidic soils. For example, Lumbricus terrestris survives at a pH of 5.4, while Dendrobaena octaedra sustains a pH as low as 4.3.

While some species, such as the manure worm (Eisenia fetida), live at the soil–litter interface (epigeic), others like the grey worm (Aporrectodea caliginosa) occupy the topsoil, forming horizontal burrows within the upper 10 to 30 cm (endogeic). Others, including Lumbricus terrestris, construct deep vertical burrows that allow them to reach the surface to feed (anecic).

Earthworms are detritivores, typically feeding on decaying leaves, grass, dead roots, and other plant parts. They also consume soil rich in humus, which contains bacteria, protozoa, nematodes, and rotifers. Additionally, many species, such as the manure worm, feed on animal feces (coprophagy), particularly cow dung, in cultivated vermicomposting environments.[4]

These annelids generate a wave-like motion using circular and longitudinal muscles of their bodies (peristalsis). When the circular muscles around each body segment contract, the worm’s body becomes thinner and elongates, whereas when the longitudinal muscles that run length-wise along the body contract, the body shortens and thickens.

The bristle-like setae on the earthworm’s body help anchor the segments to the soil. This anchoring action, along with muscular waves, generates the traction to push forward through soil.

They burrow by forcing their heads into soil cracks, aided by the secretion of lubricating mucus.

Since earthworms lack teeth, they use their prehensile prostomium to probe and push food into the mouth. Once the food is inside the mouth, strong muscular contractions in the pharynx help draw the food into the gut.

Some species of earthworms can regenerate lost body segments, but the degree of regeneration varies considerably. For example, Eisenia fetida is highly regenerative, capable of regrowing heads and tails across a range of segmental cuts.[5] Similarly, Lumbricus terrestris shows limited regeneration, replacing anterior segments from as far back as 13/14 and 16/17, though no tail regeneration is observed.

Under ideal conditions, earthworms are estimated to live for 4 to 8 years. However, in the wild, their lifespan is typically 1 to 2 years due to predation, soil disturbances, and harsh weather conditions.[6]

Most earthworms reproduce sexually, coming to the soil surface to mate, typically at night. During copulation, the worms lie ventrally against each other but in opposite directions, aligning the male genital pore of one worm (segment 15) with the spermathecal openings (segments 9 and 10) of the other worm.

After copulation, the clitellum of both worms becomes more prominent and turns a reddish to pinkish color. The clitellum secretes a sticky, mucous-like band that forms a ring around the worm’s body. Each of the two reproducing worms slowly wriggles backward through this mucous ring. As the ring passes through the female genital pore, the worm releases its eggs into the ring. Similarly, as the ring passes through the spermatheca, stored sperm from the partner are released into the same ring. Eventually, the eggs and sperm fertilize externally, and the worm slips completely out of the mucous ring, which then slides off the body. The ends of the ring then seal together, forming a cocoon. Finally, the worm deposits the cocoon in the soil, where it hatches into 2 to 20 hatchlings (depending on the species) in about three weeks. By a year, the hatchlings develop a clitellum and attain sexual maturity.

Since earthworms are hermaphrodites, from the same mating, each worm becomes both a genetic mother and a genetic father to different offspring.

Some populations of a few earthworm species, such as Aporrectodea trapezoides, are parthenogenetic, meaning they can produce cocoons and viable offspring without the need for sperm from another individual.[7]

They are preyed upon by a wide range of vertebrates and invertebrates. Among vertebrates, the most notable predators are birds such as robins, starlings, thrushes, gulls, and crows. Mammals also pose a significant threat, including moles, hedgehogs, shrews, mice, rats, badgers, pigs, wild boars, and minks. Additionally, some reptiles and amphibians, such as snakes, frogs, and salamanders, feed on them.

Among invertebrates, their predators include ground and rove beetles, ants, centipedes, spiders, snails, and slugs.

A range of endoparasites, including protozoans, flatworms, mites, and nematodes, are found living in the blood and organs of earthworms. In fact, the mite Histiostoma murchiei has been observed parasitizing the cocoons of earthworms.[8]