Earwigs are nocturnal insects that constitute the order Dermaptera. They are easily recognized by their elongated brownish bodies and a distinctive pair of forcep-like pincers at the tip of their abdomen. Moreover, their forewings are short and leathery, while the hindwings are large, membranous, and folded like a fan under the forewings. Although they have wings, many species are either flightless or fly rarely.

These insects are found almost globally (except in Antarctica), occupying dark, moist environments like under bark, rocks, or leaf litter. They are omnivores, feeding on a wide variety of food, including soft plant parts, other insects, and detritus.

The name ‘earwig’ stems from the misbelief that these insects crawl into the ears, eventually reaching the brain. However, this claim exists only in folklore and lacks scientific evidence. Around 2,000 species of earwigs are found worldwide.[1]

These insects are typically between 0.27 and 2 in (7 and 50 mm) long. The largest extant species, the Australian giant earwig (Titanolabis colossea), measures around 2 in (50 mm), whereas the largest extinct species, the Saint Helena earwig (Labidura herculeana), measured around 3 in (78 mm).

One of the smallest species known is the lesser earwig (Labia minor), which typically measures around 0.15 to 0.2 in (4 to 7 mm).

They have an elongated, dorsoventrally flattened body divided into three segments: head, thorax, and abdomen.

The head bears a pair of slender, thread-like antennae, which bear at least 10 segments. It also bears chewing-type mouthparts and a pair of compound eyes for vision.

This segment is subdivided into prothorax, mesothorax, and metathorax, each bearing a pair of legs. A large shield-like plate called the pronotum covers the prothorax, providing protection. The mesothorax bears the forewings, which are short and leathery. Similarly, the metathorax bears the hindwings, which are membranous, fan-shaped, and remain folded under the forewings.

Some species, such as Euborellia moesta, are apterous or wingless.

The abdominal segment is elongated, with ten segments. At the terminal segment lie forcep-like pincers or appendages called cerci. In males, the cerci are curved, while females have straighter ones. In females, the ovipositor is either greatly reduced or absent altogether.

They have an open circulatory system comprising a dorsal vessel, which functions as the heart and pumps hemolymph into the body cavity or hemocoel.

Like most insects, earwigs have a network of air-filled tubes or tracheae that branch throughout the body. There are numerous external openings called spiracles on their body from which air enters the trachea and finally diffuses directly to the tissues.

The digestive system is simple, with the gut divided into fore-, mid-, and hindgut segments. However, they lack the digestive gastric caecae found in many insects.

Between the midgut and the hindgut lie Malpighian tubules, which function as kidneys and filter nitrogenous waste from the hemolymph and pass it into the hindgut for excretion.

The nervous system comprises a brain, a subesophageal ganglion, three thoracic ganglia, and six abdominal ganglia.

Males of the families Karschiellidae, Pygidicranidae, Diplatyidae, Apachyidae, Anisolabisidae, and Labiduridae possess paired penises, while those of all other families have single penises.

Despite having paired penises, earwigs use only one during copulation, since females have a single genital opening behind the seventh abdominal segment.

Females possess paired ovaries, lateral oviducts, spermatheca, and a genital chamber. The sperm that they receive from the males are stored in the spermatheca.

The order Dermaptera derives its name from the Greek words derma, meaning ‘skin’, and ptera, meaning ‘wings’, which refer to their skin-like, leathery forewings.

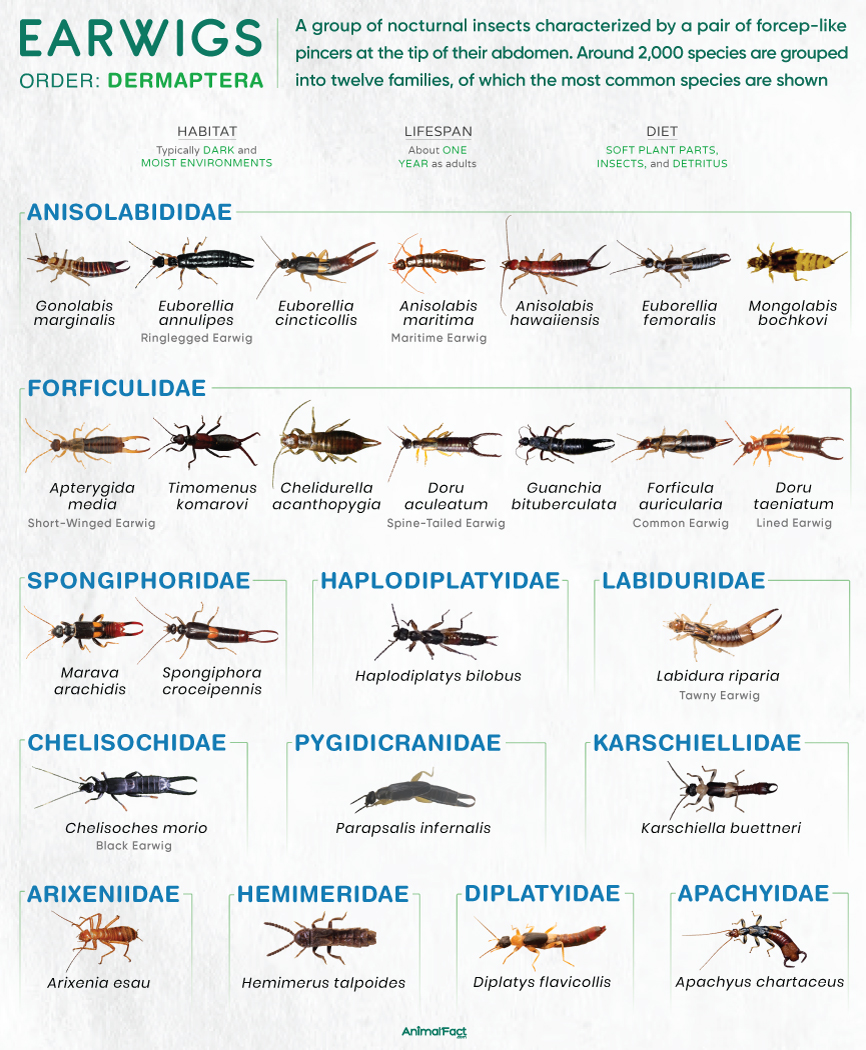

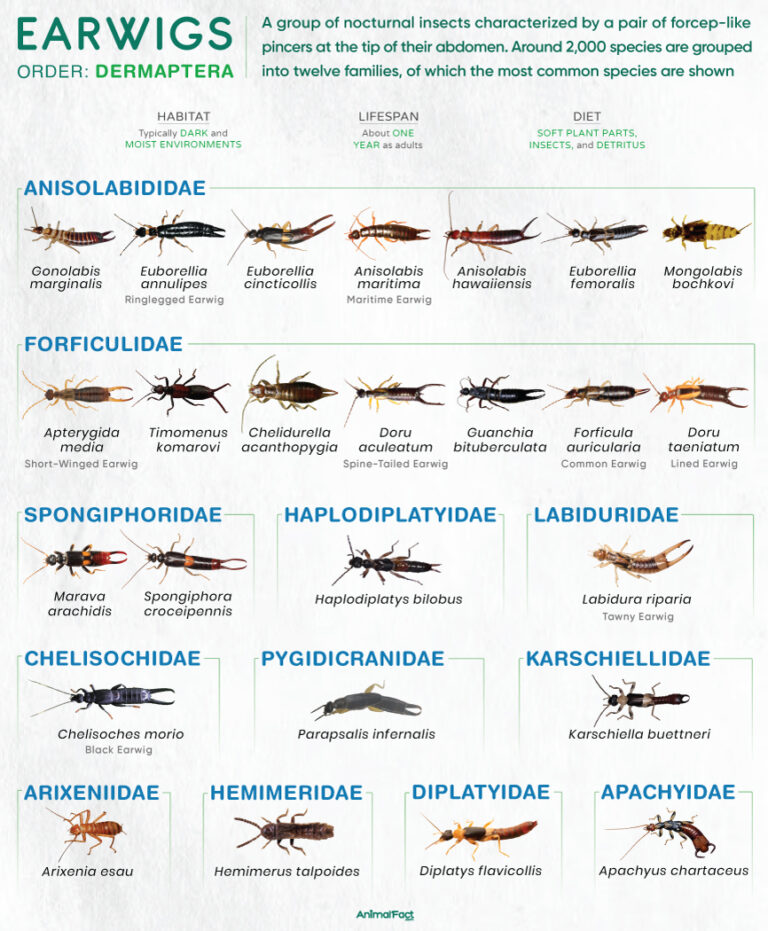

Around 2,000 species of earwigs are divided into 12 families.

These insects have an almost cosmopolitan distribution, found in all continents except Antarctica. Their diversity is the highest in the tropical regions of the southern hemisphere, whereas the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere house relatively few species.[2]

They are found throughout the Americas and Eurasia. About 25 species are found in North America, 45 in Europe, and 60 in Australia. The only native species spotted north of the United States is the spine-tailed earwig (Doru aculeatum), which extends as far north as Canada.

Native to Europe, the common earwig (Forficula auricularia) was introduced into North America in 1907 and has ever since been common in the southern and southwestern parts of the United States.

They occupy moist, protected microhabitats such as under bark, leaf litter, stones, and crevices, both in natural and man-made environments.

Most species are omnivorous and feed on both plant and animal matter. They consume the soft, tender plant parts or fruits of a variety of plants, including lettuce, strawberries, dahlias, zinnias, sunflowers, and hollyhocks. Among insects, they typically feed on aphids, mites, fleas, caterpillars, and maggots. Moreover, earwigs are scavengers, consuming decaying plants and animals.

Earwigs may occasionally feed on fungi, algae, moss, and lichens.

Some species are epizoic, living non-parasitically on the bodies of other animals. For example, members of the genus Arixenia live in the skin folds and the throat pouch of Malaysian hairless bulldog bats (Cheiromeles torquatus), most likely feeding on secretions from the bat’s body. Similarly, species of the genus Hemimerus are found on the bodies of giant-pouched rats (Cricetomys).[3]

On average, earwigs live about a year since hatching.

Earwigs begin mating in the autumn, typically within small chambers located about an inch below the surface in soil, debris, or crevices. After mating, between mid-winter and early spring, the males leave the chamber or are chased away by the females. The sperm remains in the female’s body for months before the eggs are fertilized. After fertilization, the females lay between 20 and 80 pearl-white eggs in two days. These oval-shaped eggs are about 1 mm tall and 0.8 mm wide, but they become kidney-shaped and brown before hatching. The females incubate the eggs, cleaning and protecting them. Earwigs are, in fact, one of the few non-social insects that exhibit maternal care.

Some species, such as those in the genus Hemimerus, are viviparous, giving birth to live young instead of laying eggs.[4]

In most species, depending on the environmental conditions, the eggs hatch into nymphs in 7 to 14 days. The nymphs, which resemble miniature adults, remain with their mother until their second molt, feeding either on regurgitated food provided by the mother or their own shed skin. Surprisingly, the nymphs of some species of earwigs, such as the hump earwig (Anechura harmandi), exhibit matriphagy, consuming their mother as a food source.[5]

In about 4 to 6 molts (instars), the nymphs transform into adults. They gradually attain their body color, and winged species, in particular, start to develop their wings.

Their primary predators are birds, such as starlings, blackbirds, sparrows, robins, grackles, and wrens. They are also preyed upon by spiders, centipedes, assassin bugs, ants, and beetles. Other predators include frogs, toads, lizards, and shrews.

Although not very frequently, some bats, such as Bechstein’s bat (Myotis bechsteinii), have been observed foraging for earwigs among leaf litter.[6] Moreover, the yellow jacket (Vespula maculifrons) also preys on these insects.[7]

Earwigs are parasitized by at least 26 species of parasitic fungi from the order Laboulbeniales. Additionally, adult tachinid flies (family Tachinidae) lay their eggs on or near the earwig, and their larvae eventually hatch and enter the body of the insect. The tachinid species Triarthria setipennis has been particularly observed in this regard and is used in the biological control of earwigs.

Additionally, a species of tyroglyphoid mite, Histiostoma polypori, has been observed on the bodies of common earwigs, though they are not true ectoparasites and merely hitchhike on these insects.[8]