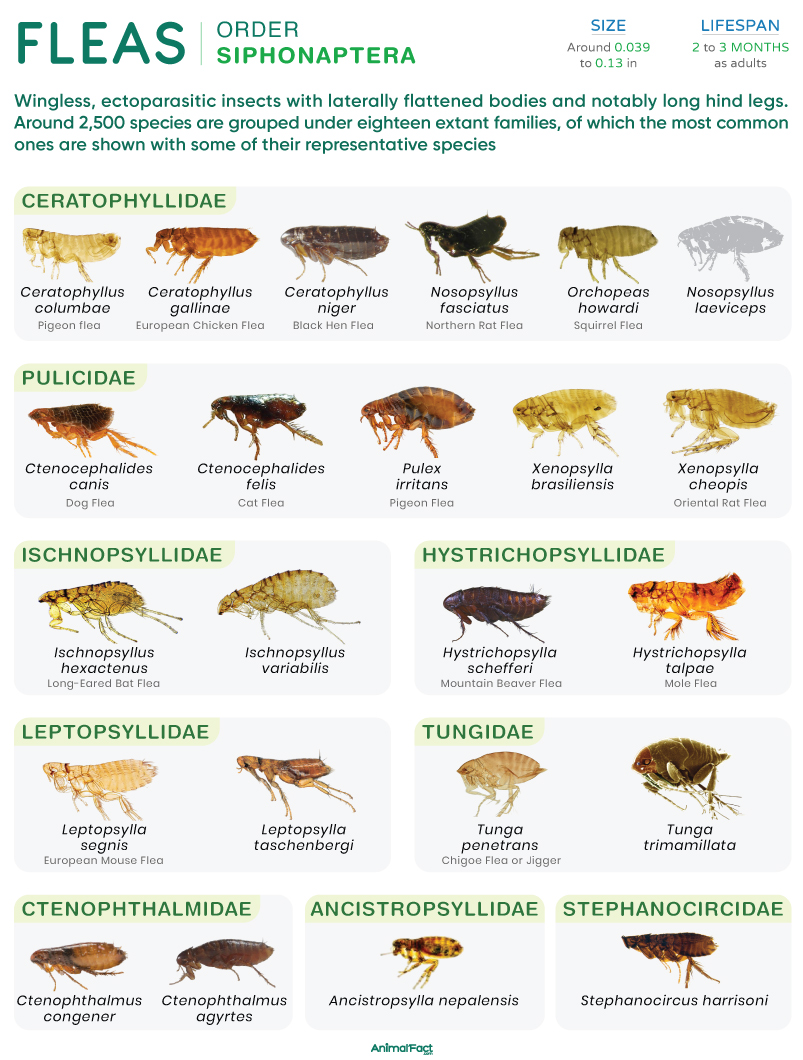

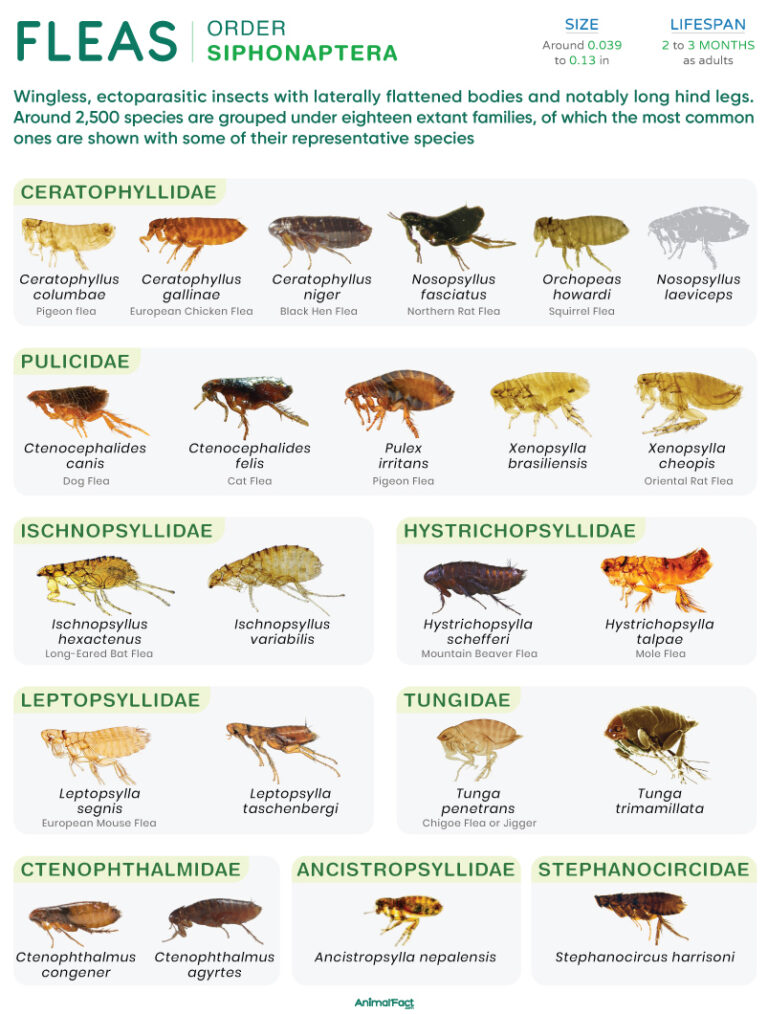

Fleas are wingless, ectoparasitic insects that constitute the order Siphonaptera. Around 2,500 species of fleas are found worldwide, of which over 94% live on mammalian hosts, whereas only about 3% are parasitic on birds. The remaining 3% include generalist fleas, those with unusual hosts (such as reptiles), or species that can switch between mammalian and avian hosts.

They are holometabolous insects that undergo four life cycle stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. While adults survive by feeding on host blood, larvae rely on organic debris, such as feces, dead skin flakes, and decaying matter.

Equipped with long hind legs, these insects are excellent at jumping, with some species capable of leaping around 50 times their body length. They possess strong claws that help them cling to the host’s body, along with specialized mouthparts to pierce the skin and suck on blood.

They act as vectors for various bacterial and rickettsial diseases of humans and other animals. One of the most notable instances of disease transmission is the spread of bubonic plague (caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis) from rodents to humans. Moreover, flea bites may cause an eczematous itchy skin disease called flea allergy dermatitis in many hosts.

Most adult fleas are around 0.039 to 0.13 in (1 to 3.2 mm) long. However, adults of the largest living flea, the mountain beaver flea (Hystrichopsylla schefferi), measure around 0.5 in (13 mm).[1] The smallest species, Tunga penetrans, measures 0.03 in (1 mm) across.[2]

Fleas have laterally flattened bodies that help them navigate easily through the fur or feathers of their host. Like all other insects, a flea’s body is divided into three distinct segments: head, thorax, and abdomen.

Their head is small and blunt, bearing a pair of short, segmented, and clubbed antennae. When not in use, the antennae lie in protective grooves on their body. While many species bear simple eyes or ocelli providing minimal vision, others are eyeless altogether.

They have specialized piercing-sucking type mouthparts characterized by needle-like structures called stylets that puncture the host’s skin during a blood meal. Their labrum and parts of the maxillae form a tubular feeding channel that helps draw the blood.

Some species, such as cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), possess comb-like spines on the lower margin of their head, which help attach to the host’s body.

The thorax is further subdivided into pro-, meso, and metathoracic regions, each bearing a pair of legs. While the front and middle legs are short, the hind legs are notably long and adapted for jumping with enlarged coxal segments. Each of the legs ends in a pair of sharp, curved claws that help anchor the insect to the body of their host. In some species, the prothorax bears a row of spines called the pronotal comb, which adds to the anchorage.

Unlike winged insects, the thorax lacks wings but contains strong muscles that control the movement of the legs through their coxal joints.

The abdominal region is typically composed of ten ring-like segments, each covered by a highly elastic cuticle that allows it to expand after a blood meal. Each segment bears sensory hairs called setae, which help detect touch, vibration, and air movement.

This region also contains the reproductive organs and parts of the digestive system. In males, the ninth and tenth abdominal segments carry claspers for securing the female during mating, along with an intromittent organ, the aedeagus, for sperm transfer. In females, the abdomen terminates in an ovipositor, which facilitates egg‑laying.

The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus first classified insects based on their wing structure (between 1735 and 1758). He proposed a group ‘Aptera,’ which included wingless invertebrates, such as fleas, spiders, woodlice, and myriapods. However, in 1810, the French zoologist Pierre André Latreille reclassified insects based on their mouthparts as well as their wings. This reclassification led to the division of Aptera into Thysanura (silverfish), Anoplura (sucking lice), and Siphonaptera (fleas).

The name Siphonaptera derives from the Greek words siphon (a tube) and aptera (wingless).

As of 2023, all flea species are divided into 18 extant families.

Fleas are believed to have descended from scorpionflies (order Mecoptera).[3] The oldest stem-group flea fossils, discovered mainly in northeastern China and Russia, date back to the Middle Jurassic through the Early Cretaceous Period. Most modern flea families originated in the Paleogene Period and onwards.

Fleas are found worldwide, with the highest species diversity in tropical and temperate regions, where warm temperatures and high humidity provide ideal conditions for their life cycle. According to the Guinness World Records, the Antarctic flea (Glaciopsyllus antarcticus), which parasitizes Antarctic sea birds, is the most southerly insect in the world.[4]

Adult fleas live as ectoparasites on the bodies of mammals and birds. Some fleas are highly host-specific, such as members of the families Malacopsyllidae (armadillos), Ischnopsyllidae (bats), and Chimaeropsyllidae (elephant shrews), whereas others, like cat and dog fleas, parasitize multiple hosts.

The eggs, larvae, and pupae of these insects are found in soil, sand, nests, burrows, floor cracks, and even in carpets.

The diet of fleas depends on which stage of their life cycle they are in. For instance, adults are obligate hematophages, feeding exclusively on the blood of birds and mammals. Some reproducing female cat fleas have been observed to consume an average of 13.6 microliters of blood per day, equivalent to about 15 times their body weight.[5]

Larval fleas, lacking piercing mouthparts, feed on feces from adult fleas, decaying plant and animal matter, as well as dead skin flakes from humans and animals.

These insects puncture the skin of their host using needle-like stylets of their mouth, injecting saliva into the skin. The saliva contains anticoagulants that prevent the blood from clotting, allowing a continuous supply of blood to be sucked up through the epipharynx.

They move by crawling on the host’s body, grasping individual hair shafts with their clawed legs. To get closer to the skin, fleas move against the direction of hair growth, often switching directions.

Owing to their long hind legs, these insects are great at jumping. Most cat fleas can jump vertically up to 7 in (18 cm) and horizontally up to 13 in (33 cm), second only to the jump of froghoppers. This jump is equivalent to a 6 ft (1.8 m) adult jumping 361 ft (110 m) vertically and 656 ft (200 m) horizontally.

The acceleration required for fleas to jump is so high that their muscles do not suffice. Instead, they have a special elastic protein called resilin in their leg joints or pads, which functions just like a spring. When the flea is about to jump, its muscles squash and stretch this resilin pad, storing up energy, just like a bowstring does. As the tension releases, the pad snaps back, launching the flea into the air.

Typically, under sufficient food and the right environmental conditions, adult fleas live for 2 to 3 months. A few species, such as the human flea (Pulex irritans), may survive over a year.[6]

However, without a blood meal, fleas can only live for a few days.

Having fed on their first blood meal, mature males and females mate on the body of their host, taking from a few seconds to a couple of minutes. While some fleas breed year-round, others may synchronize their breeding with the reproductive cycle of their hosts. For example, female rabbit fleas (Spilopsyllus cuniculi) can respond to elevated cortisol and corticosterone levels in a rabbit’s blood, reaching sexual maturity when the host is about to give birth.[7]

After fertilization of the eggs, the females get ready to lay them, either on the body of or in the habitat of the host. They lay eggs in batches of two to several dozen at a time, producing a total of 5,000 or more eggs over their lifetime. If laid on the host’s body, the eggs eventually fall off on the ground.

Since fleas are holometabolous insects, their eggs undergo larval and pupal stages before they become adults. The eggs hatch into worm-like, eyeless, and legless larvae, which feed on organic matter. They avoid sunlight, hiding in dark and humid places. Between 4 and 18 days, the larvae typically undergo three molts, weave silken cocoons, and form pupae. In a few days, after a final molt, the pupa breaks out of the cocoon, emerging as an adult.

Flea eggs and larvae are consumed by ants, beetles (especially lady beetles and carpet beetles), bugs (such as damsel bugs and bigeyed bugs), and opportunistically by wolf spiders. Some parasitic wasps lay their eggs on flea larvae so that their offspring can parasitize the fleas. Moreover, some nematodes, such as Steinernema carpocapsae, parasitize and kill flea larvae, pupae, and pre-adults.[8]

Adult fleas become targets of birds (including swallows, martins, and chickens) and lizards, such as geckos and skinks. Some small mammals, like shrews and bats, may opportunistically consume fleas while hunting other insects. In aquatic habitats, fleas that end up in water may be consumed by dragonfly nymphs and certain fish, such as mosquitofish.