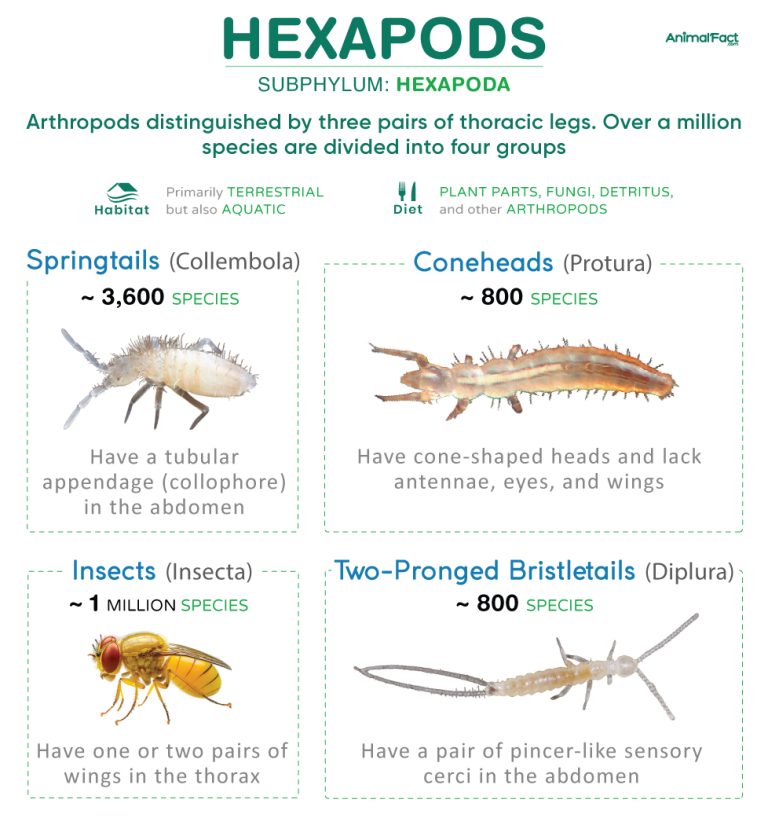

Hexapods (subphylum Hexapoda) comprise the largest of all arthropod groups, distinguished by their three pairs of thoracic legs. It includes insects, springtails, coneheads, and two-pronged bristletails, of which insects and springtails are the most abundant. They obtain their name from the Greek words hexa (meaning six) and poús (meaning foot), which justify their three-part body plan.

These animals are ecologically important since they are excellent pollinators, decomposers, soil aerators, and micropredators in terrestrial environments.

As a large group, hexapods show great diversity in their body sizes, ranging from 0.5 mm to over 300 mm (0.01 to 11.8 in) in length.

They are characterized by a three-part (tripartite) body plan composed of an anterior head, thorax, and posterior abdomen.

The head comprises a presegmental acron, which bears the eyes (absent in coneheads and two-pronged bristletails), followed by six segments.

The antennae are segmented, with each segment having its own muscles. Insects have three segments: the scape, the pedicel, and the flagellum. The flagellum lacks muscles and instead has a number of ring-like annuli (annulated antennae). In some insect groups, a sensory organ called the Johnston’s organ is found on the pedicel.

The thoracic region is partitioned into three segments (pro, meso, and metathorax), each containing a single pair of legs. Hence, in total, all hexapods have six legs, hence their name.

In most insects, the second and third thoracic segments contain wings that help in flight. Some groups, like lice and fleas, however, have no wings at all.

Newly hatched coneheads have 9 abdominal segments, while their adults have 12 segments. In contrast, springtails have six or fewer abdominal segments characterized by a tubular appendage called the collophore, projecting ventrally from the first segment. Most insects have 11 abdominal segments, followed by an additional telson (tail segment).

The abdominal appendages are highly reduced, usually limited to the external genitalia. In some groups, like two-pronged bristletails, a pair of sensory cerci are located in the final segment of the abdomen.

Traditionally, hexapods were considered close relatives of myriapods (subphylum Myriapoda), but later, in the first decade of the 21st century, they were thought to be the closest relatives of crustaceans (subphylum Crustacea).

Currently, these arthropods are broadly classified into four main groups: springtails (class Collembola), coneheads or proturans (order Protura), two-pronged bristletails or diplurans (order Diplura), and insects (class Insecta). The first two groups belong to the common ancestral group Elliplura, while the latter two are part of another higher-ranked group called Cercophora.

In an alternate taxonomy, the non-insect groups, namely Collembola, Protura, and Diplura, are placed under the class Entognatha and are hence called entognathous. In these groups, the mouthparts are enclosed within the head capsule. In contrast, members of the class Insecta are ectognathous, with their mouthparts exposed.

Hexapods are believed to have diverged from crustaceans around the Late Ordovician or Early Silurian Periods (400 to 500 million years ago). During this time, plant life was mainly restricted to the coastlines and other regions with high water availability. Some molecular studies (2002) suggest that hexapods may have diverged from their sister group, fairy shrimps (order Anacostraca), during the beginning of the Silurian Period (around 440 million years ago), in parallel to the appearance of the first vascular plants or tracheophytes.

The oldest known hexapod fossils, such as Strudiella devonica, date back to the Late Devonian Period, approximately 380 to 370 million years ago.

Though most hexapods are terrestrial, some insects, like mayflies and water striders, are aquatic and live in lakes, wetlands, and rivers. Members of Protura, Diplura, and Collembola also prefer living in damp environments to prevent desiccation of their bodies.

These arthropods, however, avoid living in sub-tidal marine areas like shallow seas and oceans.

As a broad group, hexapods feed on a wide variety of food items. For instance, diplurans feed on mites, insect larvae, and other hexapods, like springtails, whereas coneheads are found to consume mycorrhizal fungi.

Insects primarily feed on grasses, leaves, and other plant parts, whereas springtails consume spores, molds, mildews, and decaying organic matter.

Most hexapods reproduce sexually through internal fertilization, in which the males usually transfer their sperm to the female body either directly or indirectly through sperm packets called spermatophores. The males never directly inseminate the females through copulation.

Members of the groups Collembola, Protura, and Diplura undergo ametabolous metamorphosis, where the fertilized eggs directly hatch into miniature adults and grow through successive molts without any intermediate larval stages.

In contrast, insects undergo either complete (holometabolous) or partial (hemimetabolous) metamorphosis. In the first type (observed in butterflies and beetles), the eggs undergo larval and pupal stages before growing into adults. In contrast, in the second type (observed in grasshoppers), the eggs hatch into nymphs that gradually develop into adults, skipping the larval stage.

Hexapods are preyed upon by fish, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and small mammals, like shrews, bats, and hedgehogs. Sometimes, other arthropods, like arachnids, including spiders and scorpions, also feed on these animals.