Lancelets, or amphioxi, are tiny, fish-like marine organisms that belong to the subphylum Cephalochordata, in the class Leptocardii. They get their name ‘lancelets’ due to their slender, elongated body that tapers to a point at both ends, resembling the shape of a tiny sword or lance. The name ‘amphioxus’ also means ‘tapered’ (pointed on both sides). They are a group of approximately 30 species of bottom-dwelling suction feeders.

They have a rudimentary notochord, pharyngeal gill slits, a dorsal nerve cord, and a post-anal tail (and thus are classified as chordates). The notochord is a cylindrical structure similar to the spinal cord of vertebrates. Thus, these translucent fish form a vital link between the vertebrates and invertebrates.

Most species are extremely small, measuring between 1 and 3 inches. Branchiostoma lanceolatum and Branchiostoma belcheri are two of the largest lancelet species, measuring around 2.5 inches (6 cm) in length.

Except for the size, they are all generally similar in appearance, with an elongated, tapered body lacking paired fins or limbs. The only significant differences between their species are the pigmentation of their larvae and the number of spinal nerve muscles (myotomes).

These fish have several structures homologous to modern vertebrates, such as a flexible, rod-like notochord made of closely packed collagen fibers and segmented muscle blocks called myomeres. However, they also possess unique adaptations, including a simple epithelium that functions as skin and aids breathing, gills used for feeding instead of respiration, and a circulatory system that transports nutrients rather than oxygen.

A slight bump at one end of the body distinguishes their anterior region. They lack a proper tail, making them poor swimmers. Although they have some cartilage around the mouth, gill slits, and tail, they lack the complex skeleton of a vertebrate.

These fish have a hollow dorsal nerve cord running along their back, protected by a notochord. Unlike a fully developed spinal column, the notochord reaches the head, making it seem like they do not possess a true brain. However, genetic research indicates the presence of a hindbrain, a potential midbrain, and a diencephalic forebrain. Recent comparisons suggest that the di-mesencephalic primordium (DiMes) in Cephalochordata is homologous to the pretectum, thalamus, and midbrain components of vertebrates.

Lacking proper pairs of eyes, they employ opsins (light-sensitive proteins) as light detection mediums. Four special features enable vision: an unpaired frontal eye, followed by a lamellar body, Joseph’s cells, and the Hesse organs.

Inside the mouth, a group of ridges called the wheel organ houses multiple cilia. Thin, hair-like strands called oral cirri hang in front of the mouth, filtering the water before it passes through a series of gill slits in the pharynx. These gill slits are enclosed by folds in the body wall, forming the hollow atrium cavity. The endostyle, a ventral groove connected to a gland called Hatschek’s pit, produces a film of mucus over the gill slits to trap food particles. The remaining water exits through an opening called the atriopore.

The rest of the digestive tract comprises a simple tube running from the pharynx to the anus. The hepatic caecum, a pouch beneath the gut, supplies digestive enzymes and functions similarly to the liver. The food mixes with these enzymes and fully breaks down in a part of the intestine called the iliocolonic ring.

These fish lack a proper circulatory system, with no heart, red blood cells, or hemoglobin. Instead, a heart-like organ pumps nutrients along the ventral (belly) and backward through the dorsal side.

Lancelets have primitive segmented kidneys containing paired protonephridia (consisting of several flame cells connected to long tubules) instead of the nephrons found in vertebrates.

Lancelets were traditionally regarded as the sister group to vertebrates, and together, these two groups were considered the sister group to the Tunicata (also known as Urochordata). However, lancelets and tunicates exhibit significant differences in shape and the location of their notochord. Lancelets have a fish-like appearance with a notochord that extends from head to tail. In contrast, most tunicates are barrel-shaped and have notochords only in the tails of their larvae.

Initially, lancelets were classified under mollusks by Peter Simon Pallas in 1774 under the genus Limax. In 1834, Gabriel Costa introduced the new genus Branchiostoma, bringing them closer to vertebrates. They were then renamed amphioxus, now considered a scientifically obsolete term, although it is still a popular name for the group. The class Leptocardii was named by Johannes Müller in 1845, and the family Branchiostomatidae by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1846. Ernst Haeckel named the subphylum Cephalochordata in 1866.

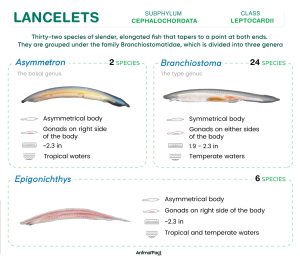

The modern classification follows the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS). All extant species fall under the family Branchiostomatidae, with Asymmetron as the basal genus and Branchiostoma as the type genus.

They are bottom-dwellers (found up to a depth of thirty meters) that inhabit warm coastal waters of the southern North Sea and Kattegat, the Bay of Biscay, and the Celtic Sea (B. lanceolatum). They are also found in the Mediterranean and Black Seas, the Atlantic Ocean coasts of North and South America (B. floridae), and the Indian and Pacific Oceans (B. belcheri and Branchiostoma japonicum).

Different species prefer specific regions and substrates:

These fish are filter feeders and consume plankton (consisting of extremely small organisms like bacteria, diatoms, fungi, and zooplankton) and detritus (dead and decaying organic matter). B. floridae feeds on particles ranging from phytoplankton to microbes (100 to 0.06 μm), while B. lanceolatum prefers those larger than 4 μm.

Lancelets swim by contracting their myomeres, which are arranged in a staggered formation along their bodies. This contraction causes them to move sideways and propel through the water. However, they lack buoyancy and quickly sink if they stop moving. Typically, they swim close to the bottom during the night.

Although capable of swimming, lancelets spend most of their time buried in the ocean floor. They burrow into the sediment using rapid wiggling movements due to their tapered bodies.

Lancelets feed by positioning themselves face-up on the sea floor, allowing water currents to pass through their gill slits. Their coughing reflex helps dislodge debris that is too large to ingest from their throat. Adults use atrial contractions for this process, while larvae rely on pharyngeal muscles.

Lancelets are gonochoric, meaning they have distinct male and female individuals with multiple segmented gonads. However, in rare cases, some species like B. lanceolatum and B. belcheri can exhibit hermaphroditism, where a small number of female gonads (usually two to five out of about fifty) develop within males. Additionally, some species, such as B. belcheri, can completely reverse their sex.

They reproduce by means of external fertilization during their spawning season, which varies among species. During spawning, sperm and egg sacs burst, releasing their contents into the surrounding water through the atriopore. This typically occurs between spring and summer in temperate regions, often after sunset. Spawning can be synchronous (happening at specific intervals) or asynchronous (gradual release throughout the season). In tropical regions, spawning can occur multiple times a year.

After almost two days, the fertilized eggs hatch into larvae. They are unusually asymmetric, with gills on the right side and the mouth and anus on the left. Additionally, parts of the nervous system, myomeres, and the pharyngeal organs follow the same trend, positioned on either side of the body cavity.

The free-swimming larvae undergo metamorphosis one to three months after hatching, transforming into adults that sink to the floor and settle among the gravel. After metamorphosis, their bodies become mostly symmetrical, except in Asymmetron and Epigonichthys, where the gonads and nervous systems remain on the right side. In contrast, members of Branchiostoma have symmetric gonads.

These fish can live for several years, often surviving seven to eight years in captivity.