Leeches are a group of typically parasitic annelids that constitute the subclass Hirudinea. Found in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial environments, leeches generally feed on the blood and other body fluids of their host animals. In fact, to adapt to a parasitic life, they are equipped with muscular suckers for attachment and hirudin, an anticoagulant peptide found in their saliva.

Around 700 species of leeches are found on all continents except Antarctica. They have been used in therapy since ancient times, originally to draw blood as part of traditional medical practices. In modern medicine, they play a crucial role in microsurgery and in the treatment of joint disorders such as epicondylitis and osteoarthritis. Moreover, their anticoagulant property helps treat blood-clotting disorders.

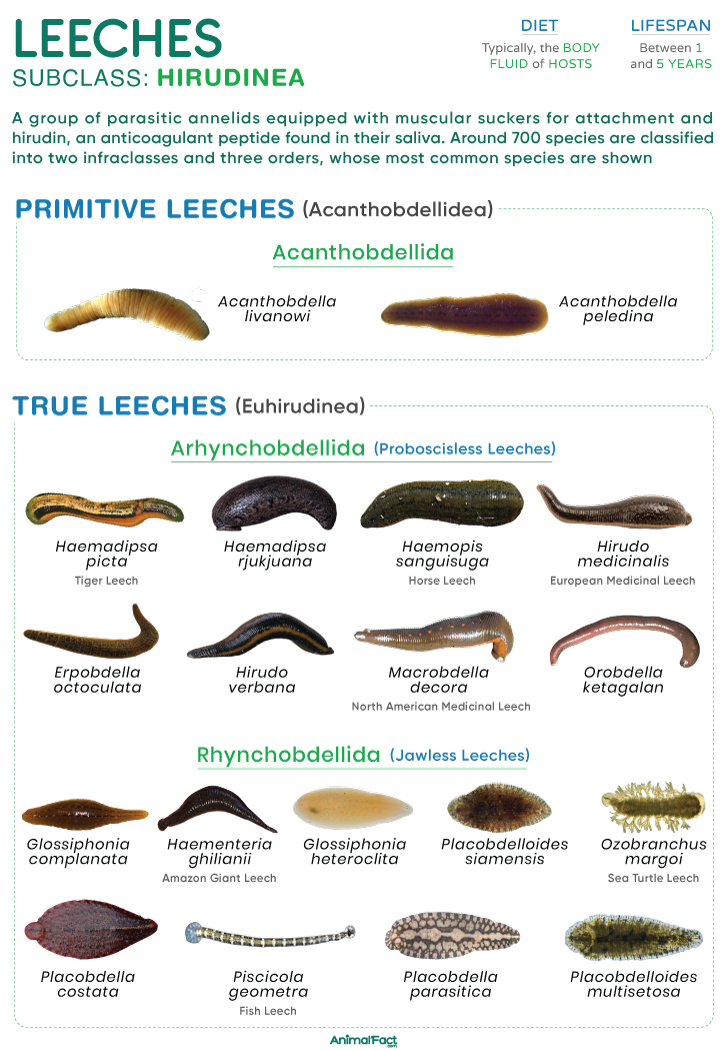

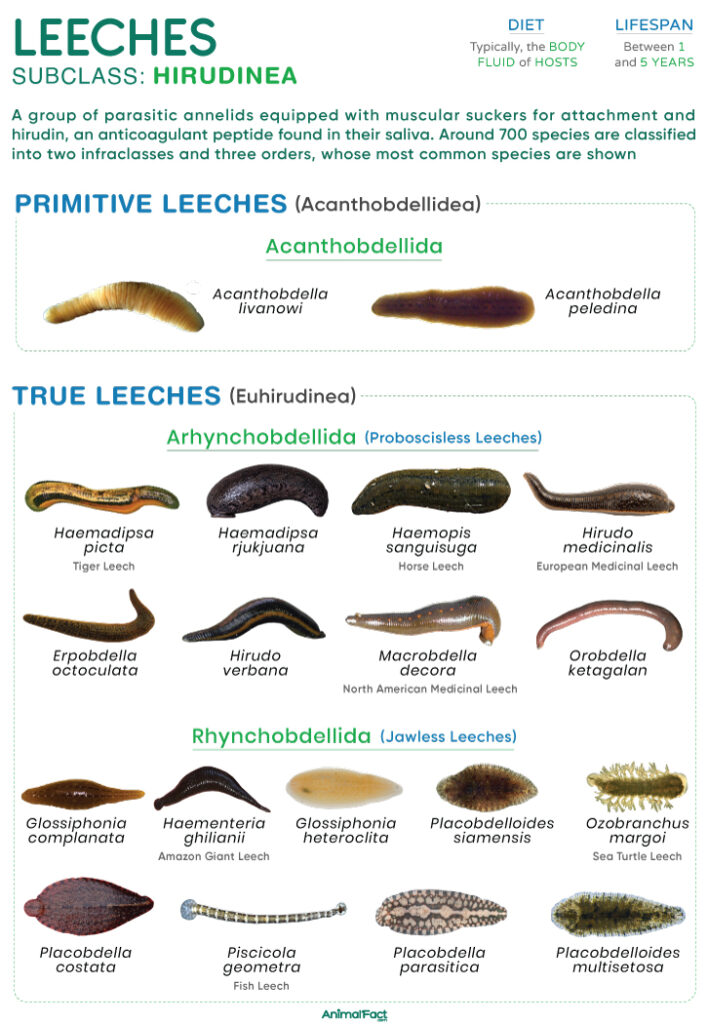

While the smallest species measure barely 0.5 in (1 cm), some of the largest ones, such as the Amazon giant leech (Haementeria ghilianii), grow up to 17.7 in (45 cm).[1]

They are characterized by a dorsoventrally flattened, muscular body, which tapers at both ends. Like most annelids, leeches are segmented, but the internal segmentation is ensheathed by secondary external ring markings or annuli, which may give the appearance of many more divisions. All leeches possess 32 true segments or somites, the first five of which constitute the head.

The head bears an anterior sucker on the ventral side, used for attachment and feeding. The middle part of the body comprises 21 segments, with each segment bearing a pair of nerve ganglia. Most species possess a thickened, glandular band of tissue or clitellum between segments 9 and 11 (though the segment number varies among species).

Towards the middle of the body lie the testes, located typically between segments 12 and 20. The ovaries, paired and small, are situated anteriorly to the testes, generally in segment 11. While the male gonopore lies ventrally between segments 10 and 11, the female gonopore lies typically between segments 11 and 12.

The last seven segments are fused to form the posterior or tail sucker.

In leeches, the true blood vascular system is replaced by a modified coelomic system called the haemocoelomic system. The body cavity contains haemocoelomic channels filled with haemocoelomic fluid.

There are four longitudinal hemocoelomic channels extending throughout the body: one dorsal, one ventral, and two lateral. The dorsal channel runs above the alimentary canal, while the ventral channel lies below it. The two lateral channels are located on either side of the alimentary canal. All four channels interconnect at segment 26 of the body.

Gaseous exchange usually occurs through the leech’s moist body cuticle. However, in marine species, respiration is aided by leaf-like lateral outgrowths of the body wall (homologous to gills) across which gas exchange takes place.

The mouth is located at the center of the anterior sucker and opens into a muscular pharynx. Depending on the type of leech, the pharynx may be protrusible, forming a proboscis (jawless leeches), or non-protrusible, equipped with jaws for cutting through tissue (probosciscless leeches). From the pharynx, food passes into a short esophagus, which leads to a large crop, the primary organ for food storage. Finally, the food moves from the crop into the intestine, where digestive enzymes break down nutrients for absorption.

Most leeches possess 17 pairs of excretory metanephridia located in segments 6 through 22 (though the exact number varies slightly among species). Additionally, they have granular, yellowish chloragogen cells that line the outer surface of the alimentary canal. These cells convert nitrogenous wastes into urea and other less toxic forms and pass them into the coelomic fluid, from where the metanephridia remove them.

These annelids are characterized by a central and a peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system comprises two large cerebral ganglia located above the pharynx, a subpharyngeal ganglion beneath the pharynx, and a ventral nerve cord that extends along the length of the body. The ventral nerve cord contains 21 pairs of segmental ganglia (in segments 6 to 26). Between segments 27 and 33, other paired ganglia fuse to form the caudal ganglion.

Each segmental ganglion sends sensory and motor nerves to the body wall and internal organs, thereby constituting the peripheral nervous system.

Depending on the species, leeches have 2 to 10 pigment ocelli cells, arranged in pairs near the anterior end, for detecting light intensity. Additionally, they have sensory papillae arranged in lateral rows, typically within one annulation of each segment. Each papilla bears numerous sensory cells that respond to touch and vibration.

The name of the subclass, Hirudinea, derives from the Latin word hirudo, which translates to ‘a leech’. All the species of leeches are traditionally classified into two infraclasses: Acanthobdellidea (primitive leeches) and Euhirudinea (true leeches).

The earliest, undisputed leech fossils date back to the Middle Permian Period (around 266 million years ago), though some specimens with leech-like external ring markings have been found to date back to the Silurian Period.[2]

Of all species of leeches, around 480 species live in freshwater environments, about 100 are marine, while the remaining are terrestrial.[3] Their highest diversity occurs in the Holarctic region.

Most freshwater leeches, including members of the family Glossiphoniidae, typically occupy the shallow, vegetated areas on the edges of the water body. They typically attach to the bodies of freshwater fish, though some parasitize frogs, salamanders, and tadpoles.

Terrestrial leeches, like those of the family Haemadipsidae, inhabit moist leaf litter or soil, latching onto animals (including humans) that pass by.

Most marine leeches, belonging to the family Piscicolidae, are found in coastal waters and estuaries, where they parasitize fish.

The diet of leeches varies among species, but they are broadly of two types: hematophagous, which feed on the blood or body fluids of other animals, and predatory, which prey on small invertebrates.

For instance, the European medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis) consumes the blood of mammals, and occasionally amphibians (when mammals are not available), whereas Erpobdella octoculata is predatory and typically feeds on larvae of chironomid flies and oligochaetes.

Most leeches survive between 1 to 5 years in the wild. However, a few species, such as the European medicinal leech, may live up to 20 years if conditions are favorable.[4]

These animals are hermaphrodites, with each individual leech bearing both male and female reproductive organs. In their reproductive cycle, the testes mature first, followed by the maturation of the ovaries.

During copulation, two leeches align their clitellar regions, allowing one to pass a spermatophore into the female gonopore, typically using the penis. However, in orders that lack a penis (such as Rhynchobdellida and Arhynchobdellida), the spermatophore is forcefully pushed by one individual through the integument of the other (traumatic or hypodermic insemination). The sperm travels through the tissues to reach the ovaries, where eggs are fertilized internally.

After fertilization, the leech secretes a mucous cocoon from the clitellum. The cocoon slides along the length of the body, collecting the fertilized eggs as it passes over the genital pores. Depending on the species, 5 to 30 eggs are laid in small clutches.

The cocoon is either deposited in damp soil near water bodies (in case of terrestrial leeches) or under submerged plants (for aquatic leeches).

After 1 to 4 weeks, the eggs hatch into juveniles within the cocoon. The juveniles attach to a host and begin feeding. They eventually grow in size, attaining sexual maturity anywhere between 2 months to a year.

Aquatic leeches are preyed upon by fish, particularly those that hunt in shallow waters. They are occasionally eaten by frogs and newts. Moreover, some predatory insects and crustaceans (such as dragonfly larvae, crayfish, and diving beetles) may consume juvenile leeches. Some birds, like ducks, herons, and egrets, may also feed on aquatic leeches in shallow waters.

Terrestrial leeches may fall prey to lizards, turtles, snakes, and small mammals.