Mammals are a group of complex warm-blooded animals belonging to the class Mammalia. They are recognized by the presence of mammary glands (which produce milk to feed the young) and a highly developed organ system (capable of performing specific functions within the body).

The term ‘Mammalia’ was coined by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, from the Latin word ‘mamma’ meaning ‘teat or ‘pap.’ These vertebrates also bear fur or hair on their bodies, have a neocortical region in their brains, and possess three middle ear ossicles or bones. They also have large brains, can use tools efficiently, and communicate through scent marking, alarm signals, songs, and echolocation. Mammals often organize themselves into fission-fusion societies, harems, and hierarchies but may also lead solitary lives.

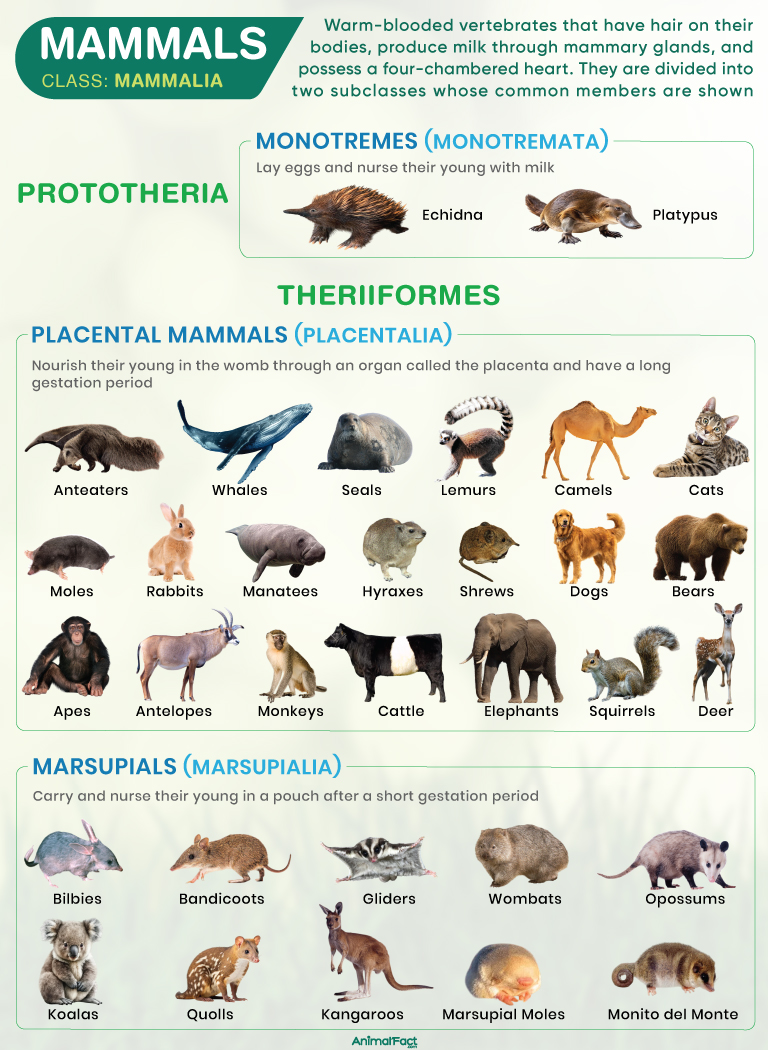

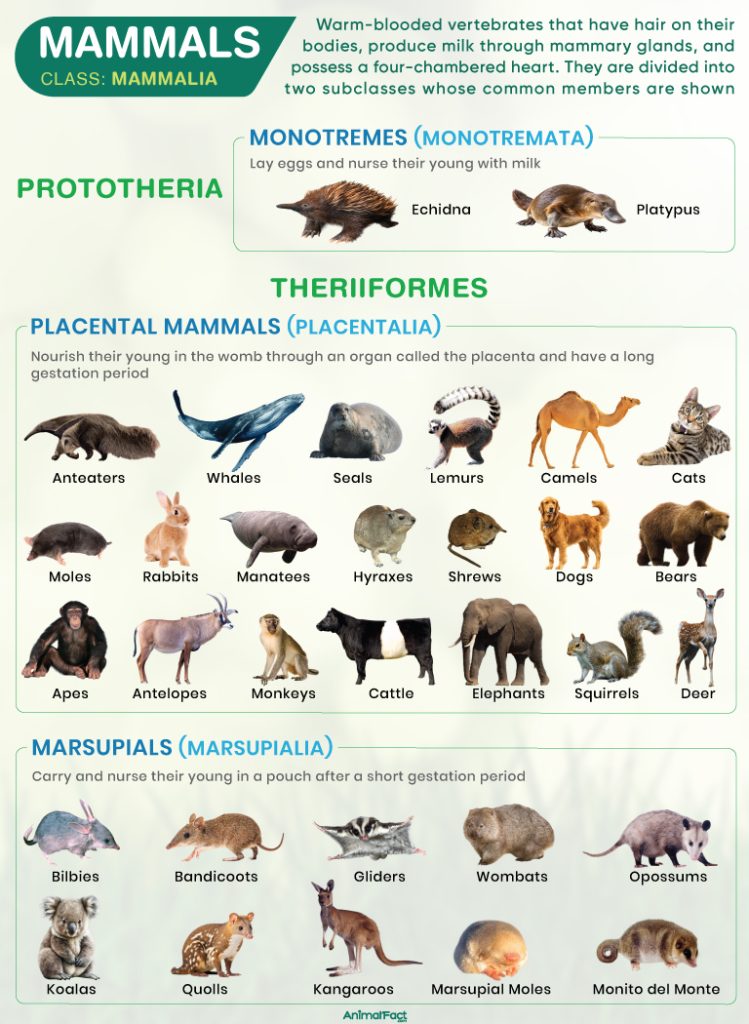

Although most mammals, including humans, are viviparous, giving birth to live young, mammals of the order Monotremata (monotremes), like echidna and platypus, are oviparous and lay eggs.

They display a wide range of sizes, with animals like bumblebee bats being as tiny as 30 to 40 mm (1.2 to 1.6 inches), while the gigantic blue whale, the largest mammal in the world, measures around 30 meters (98 feet). The Etruscan shrew (Suncus etruscus) is the smallest mammal on Earth by mass, weighing only about 1.8 gm (0.063 oz) on average.

Mammals are dimorphic based on size, with males being at least 10% bigger than females in over 45% of studied species.

Mammals have four-chambered hearts, consisting of two receiving chambers (atria) and two discharging chambers (ventricles), connected by valves that prevent blood from back-flowing.

After oxygenation in the lungs, blood enters the left atrium through pulmonary veins, where it is directed through arteries to different body organs. Deoxygenated blood is collected from the organs and propelled to the right atrium, which is then transported to the lungs.

The heart muscles also require oxygenated blood for proper functioning, which is supplied to the walls through coronary arteries.

Lungs are chambers for gaseous exchange or ventilation, which is enabled by a negative pressure pump created in the thoracic cavity with the help of the diaphragm. As air enters through the nasal cavity (inhalation) into the trachea and bronchi, the diaphragm contracts and flattens the dome, allowing the lung cavity to expand and the air to reach the minute bronchioles. On the other hand, during exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes, and the lung cavity shrinks, pushing air out of the lungs.

The alimentary canal is highly specialized in mammals, particularly herbivores, whose intestines are elongated and whose stomachs are modified according to their diet. In placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates), the stomach is divided into four sections: the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum. After the partial breakdown of food matter in the mouth, the bolus passes to the rumen and reticulum, where microbes like bacteria, fungi, or protozoa produce the enzyme cellulase that digests plant cellulose. In mammals of the order Perissodactyla, the digested food leaves the stomach and enters an enlarged pouch called the cecum, where bacteria ferment it.

Carnivores have relatively simple stomachs adapted for easy digestion of meat.

Dentition

Dental structure varies in different groups of mammals based on their feeding habits. For example, frugivores and herbivores that consume fruits and foliage have low-crowned teeth adapted for grinding soft plant parts, whereas grazers feeding on hard, silica-rich grasses possess high-crowned teeth for grinding tough plant parts. Carnivores have carnassialiforme teeth, characterized by visibly long canines that help in tearing flesh.

Mammals like toothed whales and murid rodents can replace their teeth only once in their lifetime (diphyodonty), while monophyodonts, like platypus, seals, and walrus, have a single set of teeth throughout their lives (monophyodonty). Some mammals, such as elephants, kangaroos, and manatees, have constantly growing teeth (polyphyodonty).

The central nervous system of mammals consists of the brain and the spinal cord, while the accessory nerves form the peripheral nervous system.

The forebrain contains a large cerebrum, thalamus, and hypothalamus, which integrate internal and external stimuli and channel the signals to the brain’s higher centers. Similarly, the anterior end of the hindbrain contains another important structure, the cerebellum, which integrates stimuli from the muscles and the inner ear and coordinates motor activities that help maintain posture.

Most mammals, except pinnipeds, cetaceans, and bears, have bean-shaped kidneys that excrete nitrogenous waste products in the form of urea (ureotelic). They also expel bilirubin, a waste product derived from blood cells, which gives mammalian feces its characteristic yellow color.

The kidneys have a renal cortex and a renal medulla composed of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids. They comprise excretory units called nephrons, characterized by a proximal tubule, an elongated loop of Henle, and a distal tubule that empties into a long collecting duct.

Although most adult placental mammals do not retain their cloaca (the only opening for digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts), golden moles, shrews, and tenrecs retain the orifice. The genital tract in marsupials is separate from the anus, but a trace of the cloaca is present externally.

The skin is made up of three primary layers:

Mammals are exclusively gonochoric, with individuals born with either male or female genitalia.

Males

They have a pair of sperm-producing organs called the ‘testes’ lying outside the body in a pouch called the scrotum. A set of accessory reproductive glands, such as the bulbourethral (or Cowper’s) glands, the prostate gland, and the seminal vesicles, contribute to the secretions of the spermatozoa and forming the semen. This liquid moves through the urethra into the highly vascular and erectile penis.

Females

They possess an external vulva, which is followed by the internal system containing paired oviducts, one or two uteri, cervices, and a vagina.

There are four types of uterus observed among the placentals.

In marsupials, the reproductive tract is diadelphous, with the vagina, uteri, and the oviducts all being paired.

Ever since the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus defined the class as a taxonomic rank, several revisions of the mammalian classification have been made. In 1945, Simpson, an American paleontologist, provided the systematics of mammalian relationships, which were accepted until McKenna and Bell provided fresh insights using recent palaeontological records, resulting in the McKenna/Bell classification (1997).

After inheriting the project from Simpson, the duo constructed a completely updated hierarchy that includes both living and extinct species and reflects the evolutionary history of Mammalia.

In recent decades, DNA analysis using retrotransposons has significantly improved our understanding of the evolutionary relationships among mammalian families, particularly the placentals. These molecular studies have identified three primary lineages within placental mammals: Afrotheria, Xenarthra, and Boreoeutheria, which are believed to have diverged during the Cretaceous Period. Boreoeutheria, in turn, has been subdivided into two major lineages, Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria.

Although most mammals are terrestrial and live on land, cetaceans and sirenians are fully aquatic, living in freshwater and ocean habitats. Bats are the only mammals that can fly (aerial), whereas rodents and badgers are fossorial and live in underground burrows. Some mammals, such as monkeys and possums, are arboreal, spending most of their time on trees.

Mammals within the order Carnivora are exclusively carnivorous and feed on animal flesh, while those belonging to Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla are herbivores, consuming plant matter. Most primates are omnivores, feeding on foliage, roots, and seeds.

Some mammals show varying degrees of herbivory and carnivory and are categorized into three groups:

Occasionally, obligate carnivores, like cats and dogs, may consume plant matter, while herbivores may feed on meat (zoopharmacognosy).

While most free-roaming terrestrial mammals try to fulfill their water requirements by consuming fluid-rich and fresh food, those in captivity are accustomed to drinking water. Cats, canines, and ruminants lap up water using their tongues, which are rolled into a ladle-like shape to hold the liquid.

Desert mammals living in water scarcity keep themselves hydrated by consuming succulent plants, while those living in cold environments, like hares and bighorn sheep, eat snow and icicles.

Mammals are adapted to survive in varied habitats by employing different forms of locomotion, such as walking, running, swimming, climbing, flying, or burrowing.

Plantigrade mammals, such as bears and humans, use their entire toes and metatarsals to walk flat on the ground. On the other hand, digitigrades, like cats and dogs, walk only on their toes, achieving greater stride length and more velocity. Those belonging to the orders Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla are unguligrade and walk only on the tips of their toes.

Instead of walking on all four limbs (quadrupedalism). Some mammals, like kangaroos and humans, use only two of them (bipedalism). This form of locomotion provides a larger field of vision and allows these vertebrates to employ their hands in activities like eating and handling tools.

Those living in trees employ their elongated limbs to brachiate or swing between branches. Many species, like silky anteaters, spider monkeys, and possums, use their prehensile tails to hang from the trees. Primates use frictional gripping by squeezing the tree branch between their hairless fingertips, thus generating enough friction to hold the animal.

Bats fly through the air at a constant speed by repeatedly raising and lowering their wings. The surface of their wings is dotted with small bumps called Merkel cells, which are specialized sensory cells that help them sense the air flowing over their wings.

Rodents and badgers are compulsive ground diggers, pulling up the soil to make burrows. They use these shelters to protect themselves from predators, store food, or regulate their body temperature.

Cetaceans and sirenians propel themselves through water with the help of their tail fins and flipper-like forelimbs. While their tail fins move up and down, helping in vertical motion, the flippers steer them forward, aiding in twists and turns.

Semi-aquatic mammals, like pinnipeds, possess two pairs of fore-flippers and hind-flippers for navigating through water. They use their fore-flippers like birds use their wings, alternating between power and recovery strokes and gliding in between. Their hind flippers serve as stabilizers, maintaining their balance underwater.

Most mammals communicate through various vocalizations, which play an important role in mating, serve as warning signals, and indicate food sources. They also scent-mark their territories using urine, feces, or secretions from specialized glands in their bodies.

Mammals demonstrate eusociality, the highest level of social organization, with overlapping generations within a colony of adults, cooperative division of reproductive labor, and extensive brood care. Different forms of social organization exist, like fission-fusion society, hierarchy, harems, and leks.

In a fission-fusion society, the individuals of a parent group may break off (fission) into stable subgroups due to specific circumstantial needs but rejoin (fusion) after the needs are fulfilled. For example, a group of males may leave the main group for foraging and return with prey at the end of the day.

In a hierarchy, the groups have a ranking system, with dominant individuals or alphas having higher chances of reproductive success than the submissive ones or betas. This system is best observed in harems, where only one or a few resident males get to mate with the females in the group.

Mammals, like shrews, live for about two years, while the longest-living bowhead whale survives for an impressive 211 years.

Most species are either polygynous, with one male mating with multiple females, or promiscuous, where both sexes have more than one mate. Only a few mammalian species (about 3%) are monogamous, with the males only mating with a single female. In such cases, the males provide parental care to some extent, especially when the availability of resources is low.

In mammals, like common marmosets, polyandry exists, where one female mates with several males in a breeding season. Similarly, naked mole rats have a unique mating system in which a single queen mates with multiple males and bears all the young of the society. Many mammals, such as minks and hamsters, breed seasonally, taking cues from environmental stimuli.

All viviparous mammals belong to the marsupial and placental infraclasses under the subclass Theria. Marsupials have a gestation period shorter than their estrous cycle, followed by the birth of altricial (barely developed newborns) that need further nurturing. In some species, like kangaroos, this development phase occurs in a special pouch called the ‘marsupium’ in front of the mother’s abdomen. On the other hand, in placentals, the young are born relatively more developed and are well-nourished in their fetal stage by the placenta, a temporary embryonic connection between the fetus and the mother’s uterine wall.

The newborns are fed the lactose-rich milk produced by their characteristic mammary glands (lactation). Depending upon the environmental conditions, the males may extend some parental care, including defending the territories, providing resources, or developing the offspring. As the young continue to grow, they are slowly introduced to food sources other than the mother’s milk (weaning).

Apart from the species that are apex predators or those higher in the food chain, mammals are usually preyed upon by predatory birds, reptiles, and other larger and more formidable mammals.