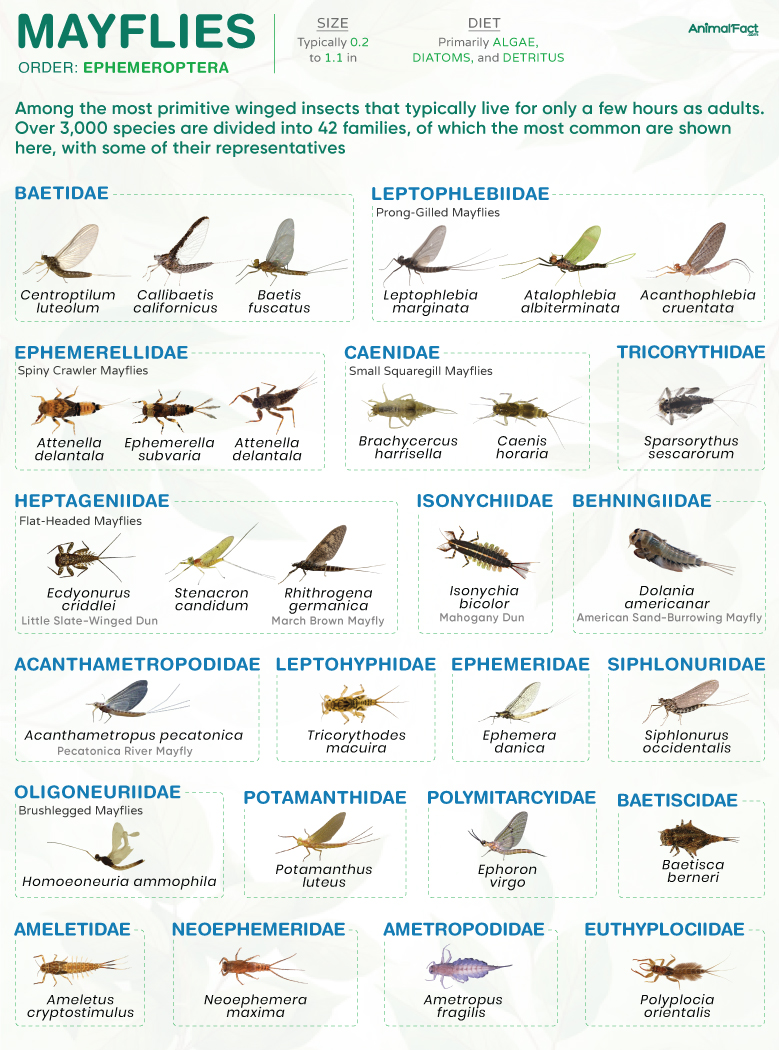

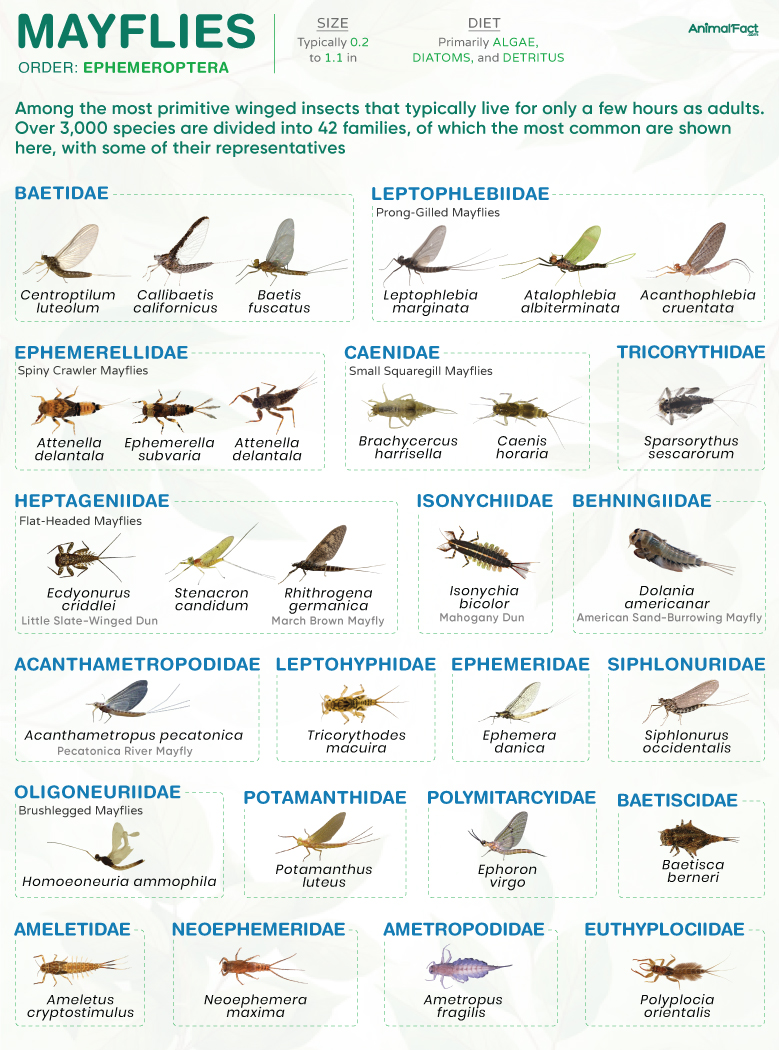

Mayflies are insects belonging to the order Ephemeroptera, which falls within Palaeoptera, a group that also includes dragonflies and damselflies. The name of the order, Ephemeroptera, refers to the ephemeral or short-lived life of mayflies as adults, typically surviving only a few hours, only to mate and reproduce.

These flies are among the most primitive winged insects, dating back to the Late Carboniferous Period. They are hemimetabolous insects that develop from nymph to adult through a series of gradual molts without passing through a pupal stage. Unique among insects, a mayfly nymph undergoes a winged subimago (subadult) stage before reaching sexual maturity and emerging as an imago (adult). In the temperate region, this emergence typically takes place in or around May, giving these insects their name, ‘mayflies’.

The nymphs, occupying clean, freshwater environments, represent the feeding stage of mayflies. The adults mate mid-air, living off the energy reserves they have built up in their nymphal stages, and lay their eggs in water.

They vary in size from 0.2 in (0.6 cm) to 1.1 in (2.8 cm)[1], with an average wingspan of 0.5 in (1.27 cm) across[2].

The anatomical features of mayflies vary with the life stage they are in.

A fully developed mayfly nymph has an elongated body comprising a head, thorax, and abdomen.

Most mayflies have up to seven pairs of gills. Depending on the species, these gills arise from the top or sides of the abdomen or are located on the coxae of the legs. Most taxa have three thread-like caudal filaments comprising a pair of cerci (tail-like appendages) attached to the last abdominal segment and a median caudal filament.

The sexually immature subimago physically resembles the adult but appears paler. Its wings are clouded in appearance and are fringed with minute hairs called microtrichia.

As poor fliers, subimagos have shorter appendages than imagos and are less showy than them.

The imago or adult of most mayflies bears two pairs of membranous, triangular wings: large forewings and small hindwings. However, in some families, like Baetidae, the hindwings are greatly reduced and appear as tiny lobes behind the forewings. The second segment of the thorax is particularly enlarged and bears the forewings.

In most species, males bear unusually long front legs, an adaptation for grasping females during mating in the air. The males of some families, such as Baetidae, have highly developed upper eyes (turbanate or turban-like eyes) in addition to the regular lateral eyes. These turbanate eyes help detect UV light and track females flying above them.

Unlike most insects, the imago of mayflies has paired sexual structures. Males possess a paired penis-like intromittent organ called aedeagi, while females have two gonopores for receiving sperm.

Imagos generally lack functional mouthparts since they do not need to feed.

The order Ephemeroptera was defined by Alpheus Hyatt and Jennie Maria Arms Sheldon in 1890–91. The name comes from the Greek words ephemeros (meaning ‘short-lived’) and pteron (meaning ‘wing’), referring to the brief adult lifespan of these insects.

In Canada and the upper Midwestern United States, mayflies are also referred to as shadflies, while in the American Great Lakes region, they are called Canadian soldiers. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, these insects are commonly referred to as up-winged flies.

There are over 3,000 species of mayflies known worldwide. According to the traditional classification introduced in 1979 by W. P. McCafferty and George F. Edmunds, all species are divided into two suborders, Pannota and Schistonota. This classification was also listed by Peters and Campbell (1991) in the book Insects of Australia[4].

However, in 2005, cladistic studies by Grimaldi and Engel challenged the traditional division into the suborders Schistonota and Pannota, a view that was further supported by subsequent research.

As of 2021, there are 42 accepted families and over 400 genera of mayflies[5].

These flies are found on every continent except Antarctica. The Neotropical realm has the highest generic diversity of mayflies, comprising 607 species in 112 genera. About 35% of species belong to the family Leptophlebiidae. On the other hand, the Holarctic realm has the highest species diversity, dominated by families like Heptageniidae, Ephemerellidae, and Baetidae. About 79% of all mayfly genera are found in a single realm[6].

The nymphs are found in streams under rocks, in sediment, or decaying vegetation. Relatively few species are also spotted in lakes. For instance, one species of the genus Hexagenia was recorded by the shoreline of Lake Erie in 2003[7].

The feeding stage in the life of mayflies is the nymph. The nymphs of most species are herbivores or detritivores, typically consuming algae, diatoms, or detritus. However, nymphs of some species, like the American sand-burrowing mayfly (Dolania americana), primarily prey on the larvae of chironomids (members of the insect family Chironomidae)[8].

Adult mayflies typically rely on the energy reserves they build up in their nymphal stages.

While adults of small species typically live for less than a day, those of relatively larger species, like Hexagenia limbata, may survive up to 2 days[9]. The American sand-burrowing mayfly has the shortest lifespan among mayflies, with adult females living for less than 5 minutes[10].

The nymphs, on the other hand, live for several months to up to 2 years, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Before mating, adult males gather in swarms a few meters above water bodies and perform a courtship dance to attract females. The females then fly into the swarm, and mating takes place mid-air. While mating, the male tightly clasps the female using the enlarged front legs. The pair typically copulates for just a few seconds.

Females usually lay between 400 and 3,000 eggs, which are released in freshwater either in small batches or in bulk. Eventually, the eggs sink to the bottom and are incubated for a few days to a year, depending on factors such as water temperature, oxygen levels, and substrate type.

Once the embryo inside the egg develops, the eggs hatch into a nymph (also known as a naiad). The nymph bears antennae, functional legs, and gills. It feeds and develops stronger legs and wing pads. Depending on the species and environmental conditions, the nymph undergoes 10 to 50 molts to become the subimago (also referred to as the dun by fly fishermen). In most species, the final molt from nymph to subimago occurs at the water surface.

The subimago is winged and incapable of mating. It flies to a nearby plant or rock, perches on it, and prepares for its final molt. Slowly, the subimago sheds its outer cuticle and molts into an adult or imago, revealing clear, shiny wings and a fully hardened exoskeleton. This molting occurs within 24 hours of the emergence of the subimago.

The imago bears mature sex organs and is ready to mate. Depending on the species, climate, and geographic region, mayflies emerge as adults between spring and autumn.

In all, mayflies undergo an incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetabolism), where they do not pass through any pupal stage and, instead, gradually transform from nymph to adult through successive molts.

Mayfly nymphs have several natural predators, the primary being fish like trout, bass, perch, and minnows. Additionally, they are preyed upon by stonefly, caddisfly, alderfly, and dragonfly larvae. Occasionally, mayflies are also consumed by water beetles, water bugs, crayfish, and amphibians like frogs and toads.

Imagos are preyed upon by birds, bats, and males of the long-tailed dance fly (Rhamphomyia longicauda)[11].