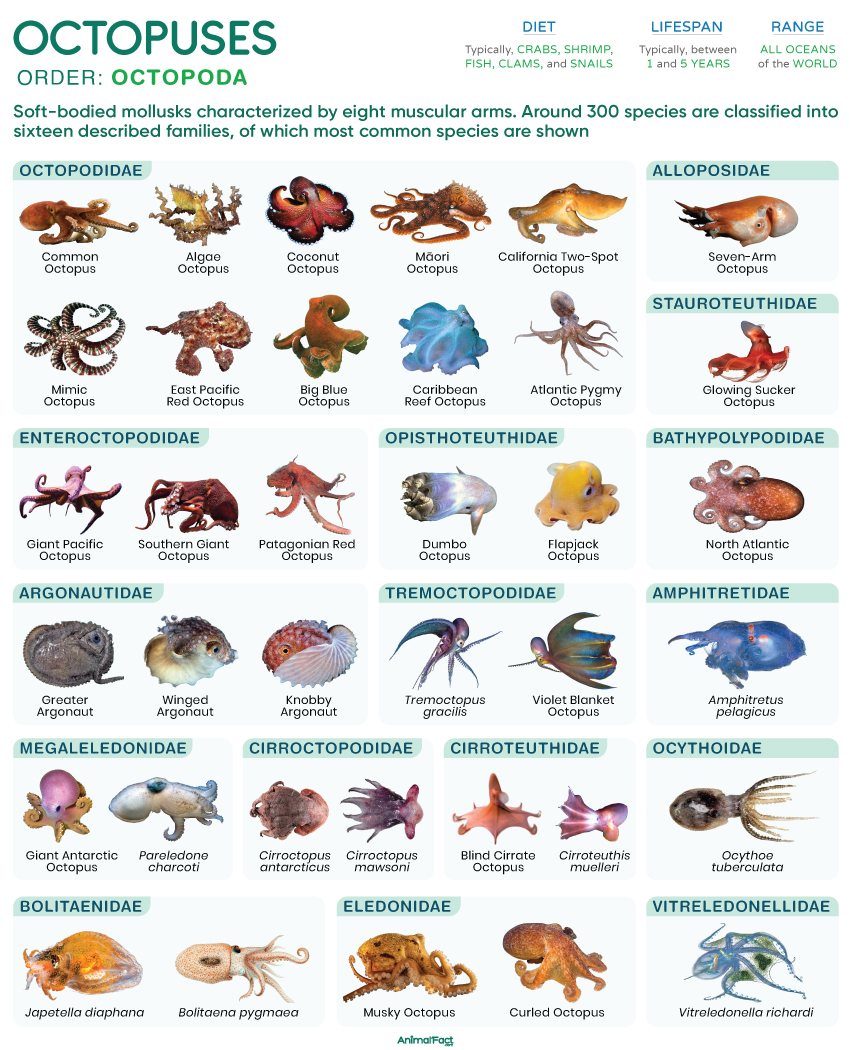

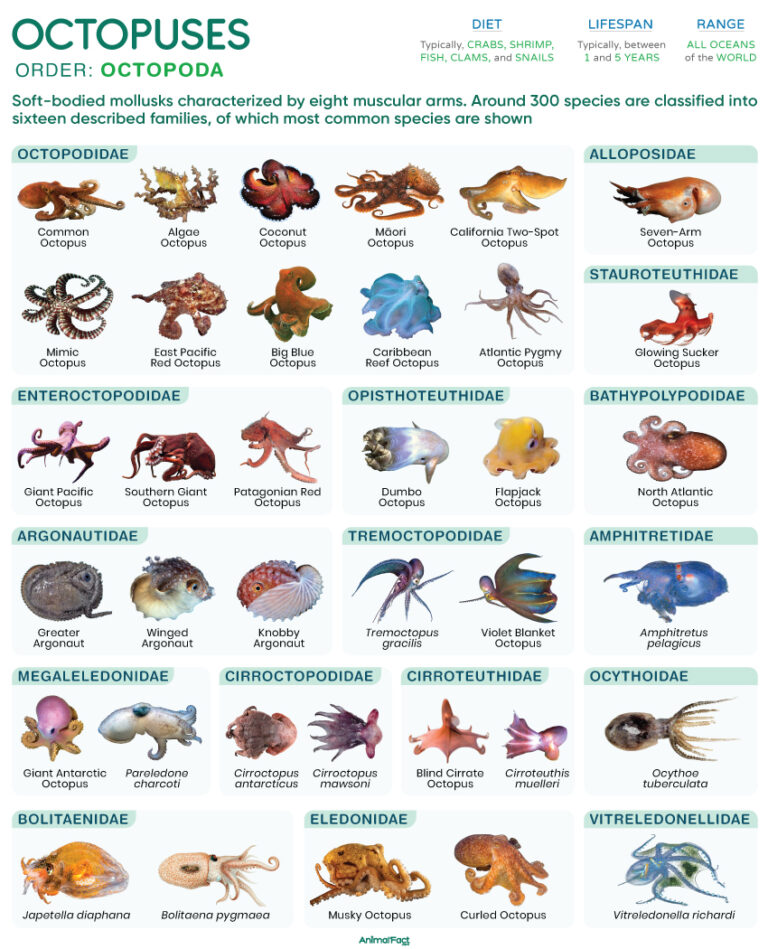

Octopuses are exclusively marine mollusks that constitute the order Octopoda within Cephalopoda, a class that also includes squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. They are easily recognized by the presence of eight arms that radiate from a central point around the mouth.

These mollusks are among the most intelligent animals, equipped with a complex nervous system that supports both short- and long-term memory, along with impressive problem-solving skills.

With around 300 species, octopuses inhabit every ocean on Earth, living in environments that range from shallow coastal waters to the deep seabed.

Their size varies considerably with species. For example, the largest species, the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), has an arm span of around 14 ft (4 m), with some larger individuals having a radial span of 20 ft (6 m) and weighing as much as 600 lb (272 kg).[1] In contrast, the smallest species, the star-sucker pygmy octopus (Octopus wolfi), is less than an inch long, weighing around 0.04 oz (1 g).[2]

They have an elongated, bilaterally symmetrical body, with eight muscular arms, lined with circular suction cups or suckers. While the two rear arms are generally used for locomotion, the remaining six are used for foraging. The head and the foot are ventral, but appear as the anterior side of the animal. As mollusks, they have a muscular mantle fused to the back of the head. The mantle cavity, which opens to the exterior through a funnel-like siphon, houses the gills, heart, and other vital organs. Lacking bones, the muscular arms function as hydrostats, helping in movement.

The suckers have an outer rim (infundibulum) that seals against the surface and an inner cup (acetabulum) that pulls back to create suction. Additionally, the suckers are sensory, capable of responding to light, even if the head remains guarded.

Their skin comprises a thin epidermal layer made of mucous cells, followed by a fibrous dermis made of collagen. The dermal layer is also equipped with specialized color-changing chromatophores (having yellow, orange, red, brown, or black pigments), which help these animals camouflage, as well as alert their conspecifics of imminent danger.

These mollusks have a closed circulatory system with a systemic heart that drives hemolymph through the body and two branchial hearts that pump it through a pair of gills for oxygenation. When the animal swims, its systemic heart stops beating.

Octopus hemolymph contains the copper-rich pigment hemocyanin, which transports oxygen throughout the body. Since this pigment makes the fluid more viscous, it is pumped under high pressure, sometimes exceeding 75 mmHg.

Apart from the gills, which are the primary respiratory organ, the skin absorbs additional oxygen. In fact, when the octopus is at rest, around 41% of oxygen absorption is through the skin. While it swims, the skin absorbs about 33%.[3]

The digestive system comprises a beaked mouth (buccal mass), within which lies a chitinous, serrated, ribbon-like organ called the radula. The buccal mass is associated with salivary glands, which secrete mucus and lubricating fluids that help move food toward the esophagus. The food passes from the esophagus to the gastrointestinal tract, which comprises a crop (for storage), a stomach (for churning with digestive secretions), and a cecum (for sorting food particles). The intestine helps absorb usable nutrients and discards indigestible material. This built-up solid waste is turned into faecal ropes and ejected through the rectum.

Nitrogenous waste, primarily ammonia, is removed by a pair of nephridia, each linked to a branchial heart. Urine forms through ultrafiltration of hemolymph in the pericardial cavity, then passes into the nephridia and is finally expelled into the mantle cavity through excretory pores near the gills.

When compared to other invertebrates, octopuses have a considerably complex nervous system, composed of over 500 million neurons. About two-thirds of these neurons are concentrated in the arms.

The nervous system is organized into the central and peripheral units. The central nervous system comprises the supraesophageal ganglia (brain) and the subesophageal mass, whereas the peripheral system constitutes the nerve cords running along each arm. They have notably large optic lobes for vision.

Like humans, octopuses have camera-like eyes with a single lens. While most species lack color vision, a few, such as the marbled octopus (Amphioctopus aegina), are capable of detecting colors.

The eyes are linked to sac-like balancing organs (statocysts), which help keep the pupils oriented horizontally, even if the animal changes direction during movement.

As gonochoric animals, octopuses have separate sexes. Males possess a single testis, vas deferens, a spermatophoric gland that packages sperm into spermatophores, a storage organ called Needham’s sac, and a specialized arm, the hectocotylus, used to transfer spermatophores into the female’s mantle cavity. The females, on the other hand, have a single ovary, paired oviducts, and large oviducal glands that coat the eggs with slimy mucous before they are released.

The order name, Octopoda, was coined in 1818 by English biologist William Elford Leach. The common name ‘octopus’ derives from the Ancient Greek words oktō (eight) and pous (foot), hinting at the characteristic eight-limbed plan of these mollusks.

Around 300 known species are classified into 16 described families.

Since octopuses are soft-bodied, their fossils are rare. However, from existing evidence, it is estimated that they originated in the Middle to Late Jurassic Period.[4]

Octopuses are widely distributed in all oceans, from tropical to polar regions. Some species, such as Megaleledone setebos and Pareledone charcoti, survive in the Antarctic waters, where the temperature reaches 29 °F (−1.8 °C).[5]

Depending on the species, octopuses occupy different habitats. For example, the Hawaiian day octopus (Octopus cyanea) lives on coral reefs, whereas the algae octopus (Abdopus aculeatus) is found in seagrass beds.

Some species, such as the spoon-armed octopus (Bathypolypus arcticus), are found at depths of approximately 3,300 ft (1,000 m). The vent octopus (Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis) lives even deeper, at depths of 6,600 ft (2,000 m).

As carnivorous predators, octopuses feed on crustaceans, like crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and amphipods, as well as other mollusks, including clams and mussels. They may opportunistically consume small fish species.

The giant Pacific octopus has been observed hunting sharks.[6]

Although most species are solitary, a few, such as Octopus tetricus, are social. The larger Pacific striped octopus (yet to be scientifically described as a species) has been observed living in groups of up to 40.

While some species actively sense their prey using the suckers on their arms, others may stealthily lurk and wait for their prey to approach. Since most of their prey are hard-shelled, octopuses typically pierce the shell using their beaks, injecting venomous saliva through the radula to kill the prey. Some species may also drill a hole in the shell, inject digestive enzymes, and then suck out the softened tissues.

Some groups, like the dumbo octopus (Grimpoteuthis), have a greatly reduced radula and swallow the prey whole.

They typically crawl slowly, using their suckers to grip and pull themselves along the sea floor. Some species, such as the veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus), crawl on just two arms while keeping the others curled.

Their fastest mode of locomotion is swimming. They fill their mantle cavity with water and then expel it forcefully through the siphon. During this action, the arms trail behind, and the body appears streamlined. By adjusting the siphon’s direction, they steer themselves forward or backward.

Finned octopuses, such as members of the family Cirroteuthidae, fail to produce jet propulsion and swim using their fins.

To prevent confronting predators, octopuses spend as much as 40% of the day hidden in their dens. Some species, such as the Atlantic white-spotted octopus (Callistoctopus macropus), display deimatic behavior by flashing a vivid red coloration with striking white spots across their bodies. Similarly, blue-ringed octopuses (genus Hapalochlaena) flash their iridescent blue rings to scare away their predators.

Many species, including Bock’s pygmy octopus (Octopus bocki), release ink from specialized glands, creating a cloud that acts as a smoke screen and allows them to escape easily.

The lifespan of octopuses varies with species. For instance, small-to-medium species, such as the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris), live for about 2 years on average, while larger ones, like the giant Pacific octopus, live between 3 and 5 years in the wild.[7][8]

They survive outside water for a brief span of about 20 to 30 minutes.

Although reproduction in most octopus species remains unstudied, a few species, such as the giant Pacific octopus, have been well-researched. Males typically engage in courtship displays by changing their body color and may cling to the top or side of the females before copulating. The male picks up a spermatophore from his storage sac with the hectocotylus, transferring it to the female’s mantle cavity close to the opening of the oviduct.

After the eggs are fertilized internally, typically a month after mating, the female lays her eggs in strings within a shelter. While the giant Pacific octopus can lay 180,000 eggs in a single clutch, others, like the common octopus, may lay up to 500,000 eggs. The eggs of the giant Pacific octopus take about 5 months to develop and hatch into planktonic paralarvae, which resemble miniature adults. They feed and eventually settle on the ocean floor as juveniles, gradually transforming into adults.

Octopuses are preyed upon by a wide variety of animals, including marine mammals such as dolphins, seals, and sperm whales, as well as large predatory fish like groupers, moray eels, and sharks. Several seabirds, including gulls, herons, albatrosses, and penguins, also feed on them. Additionally, young or injured individuals may fall victim to crabs and lobsters.

Some species, such as common octopuses, have been found to cannibalize younger individuals, typically 4 to 5 times smaller in body weight.[9]