Sea anemones are soft-bodied marine invertebrates in the order Actiniaria, a part of the phylum Cnidaria, which also includes corals, jellyfish, and hydroids. They exist as polyps, characterized by a cylindrical, columnar body with an oral disc on the top and a pedal disc at the base. Their mouth is surrounded by one or more whorls of tentacles that are equipped with defensive stinging cells called cnidocysts.

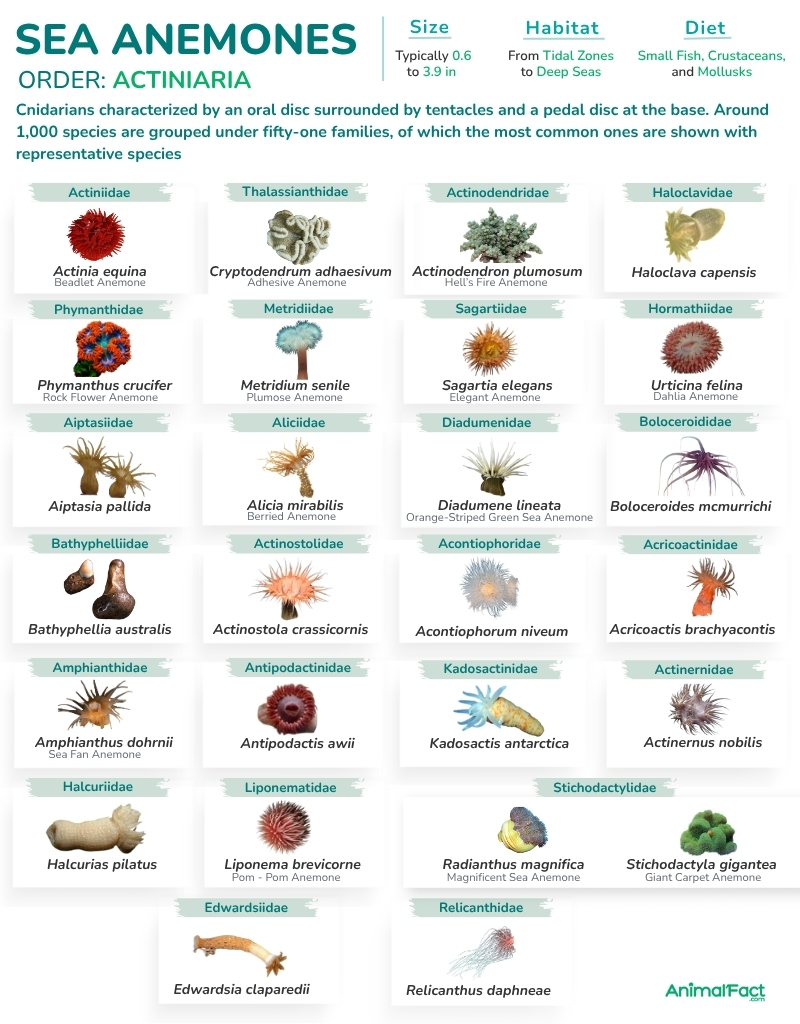

Over 1,000 species are found in the oceans worldwide, ranging from shallow coral reefs to the deep sea. Most remain sessile, anchored to a substrate by their pedal disc. They are carnivorous predators that typically feed on small fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and sometimes marine worms.

Almost all sea anemones are regenerative, capable of replacing lost body parts such as tentacles, portions of the oral disc, or even sections of the column.

These animals typically measure around 0.4 to 2.0 in (1 to 5 cm) in diameter and 0.6 to 3.9 in (1.5 to 10 cm) in length. However, Urticina columbiana and Stichodactyla mertensii, among the largest species, measure over 3.3 ft (1 m). In contrast, one of the smallest species, the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis), rarely exceeds 0.6 in (1.5 cm) in length.

They have a columnar body with an oral disc on the top and an adhesive pedal disc at the base. The oral disc bears a slit-shaped mouth, which also serves as the anus, while the basal disc facilitates attachment to a substrate. Surrounding the mouth are one or more whorls of tentacles, which are armed with stinging cells (cnidocysts), a characteristic of all cnidarians. These cells contain capsule-like organelles, the nematocysts, which play a crucial role in both defense and capturing prey.

Each nematocyst contains a venom-filled vesicle loaded with actinotoxins, an inner filament, and an external sensory hair. When the sensory hair is touched, the nematocyst fires a harpoon-like filament that penetrates the predator and injects a dose of neurotoxic venom into its body.

Some sea anemones, especially members of the family Actiniidae, have nematocysts arranged in long, thread-like filaments (acontia), which, when needed, are everted either through the mouth or small pores in the body wall.

Sea anemones lack a heart, blood, or any true circulatory system. Instead, they rely on a central gastrovascular cavity, which is divided into chambers by mesenteries that extend inward from the body wall. The water within this cavity helps distribute nutrients and gases throughout the body tissues.

Lacking specialized respiratory organs, oxygen diffuses directly through their epidermis, while carbon dioxide diffuses out of it in the opposite direction.

The mouth is followed by the pharynx, which leads to the gastrovascular cavity. The mesenteries that partition the cavity are arranged in multiples of twelve around the central lumen of the sea anemone’s body. Each mesentery is made of two layers of the gastrodermis separated by a thin, jelly-like layer of mesoglea. Additionally, the mesenteries bear filaments of specialized cells that secrete digestive enzymes, helping break down food inside the cavity.

The undigested food particles move back to the mouth and are expelled through it.

They have a simple muscular system comprising epithelio-muscle cells within the body wall. These cells have microfilaments that group into contractile fibers, which provide the animal with the flexibility to move.

The muscle fibers are arranged both circularly and longitudinally. The circular fibers encircle the body, whereas the longitudinal fibers run along the entire length of it.

These cnidarians have a simple, decentralized nervous system, lacking a brain or spinal cord. They possess two nerve nets, one in the epidermis and the other in the gastrodermis. Additionally, there are nerve rings around the oral disc and tentacles, which coordinate feeding and movement of the tentacles.

Although sea anemones lack specialized sense organs, they possess simple mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors, which help them sense their surroundings.

Over 1,000 species of sea anemones are classified into 3 suborders and 51 families.

Since most sea anemones lack hard body parts that fossilize easily, their remains are scanty. The earliest fossils, belonging to the genus Mackenzia, date back to the Middle Cambrian Period.

The greatest diversity of sea anemones is found in the tropics, though they are also found in colder, temperate waters. In fact, Edwardsiella andrillae lives anchored to the underside of sea ice offshore of Antarctica.[1]

While many species inhabit tidal and intertidal zones, others are also found in deep seas. For instance, Actinostola callosa has been recorded at depths as low as about 6,715 ft (2,047 m).[2] In contrast, some species, such as Anactinia pelagica, are pelagic, found floating upside down near the water surface.

Sea anemones are carnivorous opportunists that feed on small fish, crustaceans (such as shrimp and crabs), mollusks (including snails and bivalves), and, occasionally, marine worms.

The larvae of a few species, such as the twelve-tentacled parasitic anemone (Peachia quinquecapitata), parasitize the medusae of jellyfish, feeding on their gonads and other tissues.[3]

Although most sea anemones are sessile, attached to a substrate with the help of their basal disc, some species are capable of movement. For example, Gonactinia prolifera moves by making short looping steps. It attaches a tentacle to the substrate, detaches its base, pulls the body forward, reattaches, and repeats the sequence. Moreover, when disturbed, this species also swims by using its tentacles like oars.[4]

In response to a predator, Stomphia coccinea can quickly bend and straighten its body column, swimming in strong, rhythmic flexes.[5]

The onion anemone (Paranthus rapiformis) is capable of burrowing into the sediment. Its pedal disc has been replaced by a rounded end (physa), which pushes into soft sediment and anchors itself. It then inflates and inverts while the anemone contracts, pulling its body deeper into the sand.[6]

When these cnidarians come in contact with a potential prey, the nematocysts fire their harpoon-like filaments and eventually inject toxins into the prey’s body to paralyze or kill it. Once the prey is immobilized, they use their tentacles to grip and move it to the mouth.

They engage in a mutualistic relationship with some single-celled algae species, which take shelter in the gastrodermal cells of the sea anemone’s body. While the anemone benefits from the byproducts of the algae’s photosynthesis, such as oxygen and nutrients in the form of glycerol and glucose, the algae get protection from micro-feeders.

Apart from algae, several fish and invertebrates also live in association with sea anemones. One of the most notable examples is that of clownfish (Amphiprion), which receives protection from the anemone’s stinging cells, while providing nutrition to the cnidarian through its feces. Other symbionts include cardinalfish, several crabs, some opossum shrimp, and various marine snails.

Although longevity varies among species, these animals generally tend to have long lifespans for invertebrates. For example, the giant green anemone (Anthopleura xanthogrammica) has lived a maximum of 80 years under human care, and scientists estimate that this species can live up to 150 years.[7] On the other hand, a few species, such as Bartholomea annulata, survive only around 1.5 to 2 years in the wild.[8]

While some species, such as the beadlet anemone (Actinia equina), are dioecious, with separate male and female sexes, others are sequential hermaphrodites, switching their sex at some stage in their life. In sexual reproduction, the males and females release their gametes in water. The gametes typically fertilize externally, but in some species, the female draws in water (and incidentally sperm) through her mouth into the gastrovascular cavity, where the eggs are fertilized internally.

The embryos develop into planula larvae, which drift around for a while, settle onto a substrate, and begin metamorphosing into a juvenile polyp. The polyp attains sexual maturity in 8 to 10 weeks.

Different species undergo various modes of asexual reproduction, including budding, fragmentation, or longitudinal or transverse binary fission. While members of Anthopleura undergo longitudinal fission, transverse fission occurs in Anthopleura stellula and Gonactinia prolifera. Some species, like Anthopleura elegantissima, undergo pedal laceration, in which the anemone creeps slowly along a surface, with small pieces of its pedal disc tearing off and remaining behind. These leftover bits, known as pedal lacerate, regenerate into new clonal individuals.

Species, such as the starlet sea anemone, produce buds along the column, which eventually develop into daughter anemones.[9]

Although sea anemones defend themselves with stinging cells, they are sometimes eaten by certain fish (such as butterflyfish and filefish), some sea slugs, and a few starfish species. Hawksbill sea turtles may rarely consume them opportunistically.[10]