Sea cucumbers, or holothurians, are marine invertebrates with elongated, cylindrical bodies covered in soft, leathery skin resembling the fruit of a cucumber plant. They are related to starfish, sea urchins, and feather stars and belong to the class Holothuroidea, one of the five extant classes within the phylum Echinodermata.

As echinoderms, sea cucumbers exhibit pentamerous radial symmetry (though not visible from outside), possess specialized tube feet for locomotion, and have up to 30 oral tentacles for gathering food. Their calcareous endoskeleton consists of microscopic ossicles, which sometimes form larger plates, giving them a scaly appearance.

They are found worldwide, primarily as benthic organisms attached to sediments on the ocean floor. They feed by scavenging debris and consuming plankton from the water.

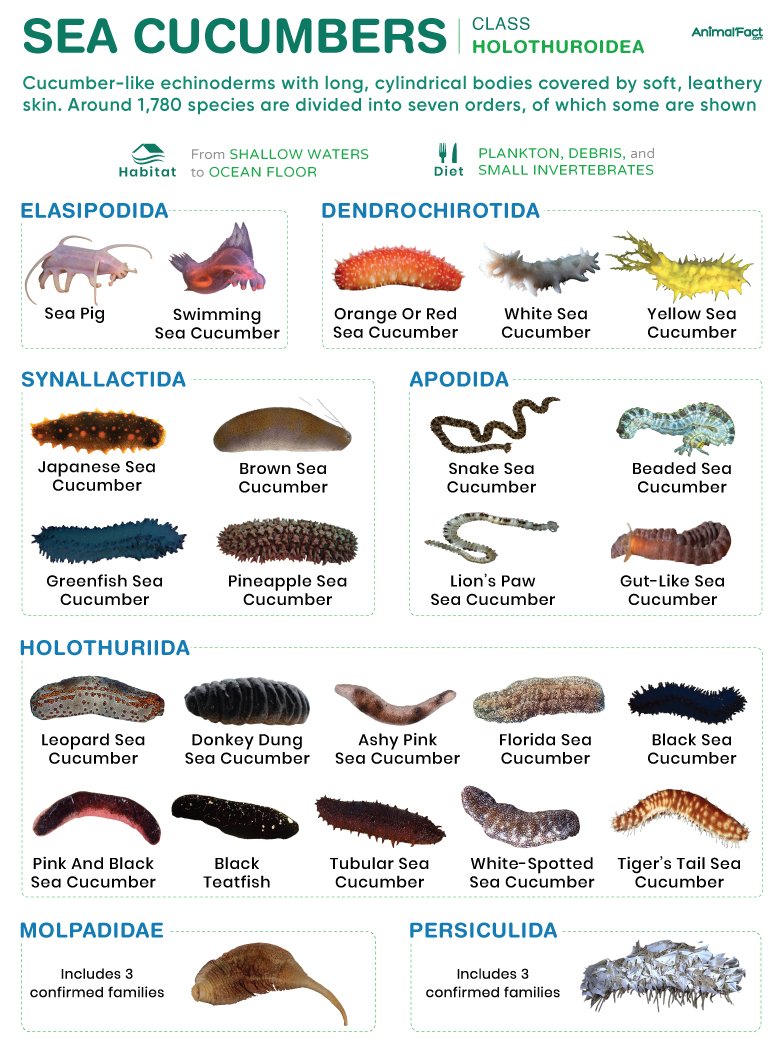

Currently, around 1,786 recognized species of sea cucumbers are classified into two extant subclasses and seven orders.

Sea cucumbers come in a variety of sizes but typically range between 3.9 to 11.8 in (about 10 to 30 cm) in length, though they can vary greatly in size, with the largest species, Synapta maculata, reaching up to 10 ft (3 m) and the smallest measuring just 0.12 in (3 mm).

The largest American species, Holothuria floridana, measures between 10 and 12 in (25 to 30 cm) in length.

Sea cucumbers typically have a soft, cylindrical body with bilateral symmetry, often tapering or rounded at both ends. However, their body shape can vary significantly, ranging from almost spherical forms, as seen in the genus Pseudocolochirus, to snake-like, as found in the order Apodida. While they lack the obvious pentamerous symmetry characteristic of sea stars, they retain this symmetry internally.

Like other echinoderms, sea cucumbers possess a water vascular system that provides the hydraulic pressure necessary for the movement of these animals. This system comprises a central ring with five radiating ambulacra, which are separated by grooves called interambulacra. These grooves contain up to five rows of swollen ampullae-like structures called tube feet or podia. On the dorsal side of the body, these podia are reduced to small papillae, as they do not play a role in locomotion. Notably, species in the order Apodida lack tube feet entirely.

At the anterior end of the body, the mouth is surrounded by a ring of up to 30 retractable tentacles used for capturing prey. Unlike other echinoderms, sea cucumbers do not have distinct oral and aboral surfaces. Instead, they rest on their ventral side, which features three rows of tube feet (the trivium), while the dorsal side has only two rows (the bivium).

The body wall of sea cucumbers comprises an outer epidermal layer and an inner dermal layer. Together, these layers enclose the coelom, or body cavity, which is divided by three longitudinal mesenteries that provide support for the internal organs.

As echinoderms, sea cucumbers have a calcareous endoskeleton comprising microscopic ossicles embedded in the skin. In some genera, like Sphaerothuria, these ossicles are enlarged to form flattened plates resembling a scaly armor. However, in some pelagic species, such as Pelagothuria natatrix, the endoskeleton is completely absent.

Sea cucumbers have a relatively complex circulatory system comprising well-developed blood vessels and open sinuses. It is characterized by a central haemal ring that lies next to the ring canal of the water vascular system. A network of blood vessels emerge from this ring and emerge from the radial canals under the ambulacral grooves.

Larger sea cucumbers have additional vessels surrounding the intestine, which are connected to numerous tiny ampullae that function as miniature hearts.

Their blood contains unique phagocytic coelomocytes, which are functionally similar to vertebrate white blood cells and play an important role in immunity. Another type of coelomocyte found in these animals contains hemoglobin and confers a red color to the blood of most species.

The metal vanadium has also been recorded in the blood of sea cucumbers.

The primary respiratory organs in sea cucumbers are a pair of respiratory trees branching within the cloaca. These trees are composed of narrow, thin-walled tubules that run along the digestive tract, facilitating gaseous exchange through their walls.

Besides being respiratory in function, these trees also help in excretion by facilitating the exchange of ammonia across their walls. Additionally, solid waste particles are also expelled through the phagocytic coelomocytes.

The mouth is followed by a pharynx, which is encircled by a ring of ten calcareous plates. These plates serve as the attachment point for the muscles that control the tentacles.

In most species, the pharynx is followed by an esophagus and a stomach, though in some, it may directly open into a long, coiled intestine. The intestine loops thrice inside the body and ends in either a cloaca or directly as the anus.

Although these animals lack a true brain, a distinct neural ring surrounds their oral cavity, innervating the tentacles and the pharynx. Five major nerves radiate from this ring and run down the length of the body under each ambulacral groove.

In most species, there are no sensory organs, except for nerve endings scattered throughout the skin, which help sense light or touch. However, members of the order Apodida possess specialized balancing organs called statocysts. Some species, like the leopard sea cucumber, also possess tiny eye spots at the base of their tentacles.

Classifying holothurians is a challenging task, as their paleontological history is based on a scarce number of fossils.

The modern taxonomic classification of sea cucumbers is based on the presence of some of the soft parts of their bodies, such as lungs, podia, tentacles, and peripharingal crowns, along with their shape. The identification of genera and species is based on the microscopic examination of ossicles, the small skeletal elements in their bodies.

Currently, almost 1,786 known species are divided into 2 extant subclasses and 7 orders. These orders are primarily distinguished by the structure of their oral tentacles. For example, members of the order Apodida have around 25 simple or pinnate tentacles, while those in Synallactida possess 10 to 30 leaf-like or shield-shaped tentacles. Similarly, Dendrochirotida species have 8 to 30 long, intricately branched tentacles.

The order Apodida is considered the sister group to all other orders of Holothuroidea.

Sea cucumbers are distributed worldwide, inhabiting environments ranging from shallow waters to the extreme depths of the ocean. While adult sea cucumbers are primarily benthic, living attached to or moving along the seabed, their larvae are planktonic and drift freely in the water column.

At depths exceeding 8,900 m (29,200 ft), sea cucumbers make up about 90% of the total macrofaunal biomass. Their diversity notably increases beyond depths of 5,000 m (16,000 ft). For example, sea pigs (family Elpidiidae) are commonly found at depths greater than 9,500 m (31,200 ft), and species from the genus Myriotrochus have been documented at similar depths.

The strawberry sea cucumber (Squamocnus brevidentis) displays remarkable adaptability to specific environments. It thrives on the rocky slopes surrounding the southern coast of New Zealand’s South Island, where its population density can reach up to 1,000 animals/m2 (93 animals/sq ft).

They primarily feed by scavenging on debris and decaying organic matter in the benthic zone (sea floor). They also consume plankton and other small aquatic invertebrates.

These animals usually position themselves in currents and wave their tentacles to catch plankton (suspension feeding). Once inside the mouth, they break the food into smaller pieces.

They may also dig into the bottom silt or sand, burying themselves and extruding their tentacles to obtain detritus (deposit feeding).

Like most echinoderms, sea cucumbers primarily use their tube feet for locomotion, though members of the order Apodida, lacking these feet, burrow through sediments by contracting their body muscles, just like worms.

Some species, like Hansenothuria benti, can swim rapidly for a few minutes by flexing their anterior and posterior ends into S-shaped curves.

On sensing threat, some sea cucumbers of the order Aspidochirotida extend sticky enlargements of their respiratory trees called Cuverian tubules to entangle their enemies. These tubules are extended through a tear in the cloacal wall (evisceration). Sometimes, evisceration is followed by the release of a toxic chemical called holothurin, which incapacitates and eventually kills any predator lurking nearby.

Some species, such as the leopard sea cucumber, defend themselves by violently contracting their body muscles to eject internal organs like the gut through their anus, a mechanism that scares their predators away.

Most sea cucumbers are dioecious, with distinct male and female individuals. However, some species, such as the burrowing sea cucumber (Leptosynapta clarki), exhibit protandry, starting life as males and later transitioning to females.

In the majority of species, reproduction occurs externally, with males and females releasing sperm and eggs into the water, where fertilization takes place. Conversely, around 30 species, including the red-chested sea cucumber (Pseudocnella insolens), practice internal fertilization. In these cases, fertilized eggs are transferred to a specialized pouch on the adult’s body, where they develop and hatch directly into juveniles. In other species, the zygote develops inside the body cavity and is born as a juvenile through a small rupture near the anus.

Although in a few cases (as mentioned above), the zygote directly grows into a juvenile, in most sea cucumbers, the fertilized eggs develop into the first larval stage, the auricularia. This larva has a long ciliated band wrapped around its body (like the bipinnaria larva of starfish), which it uses to swim.

The auricularia grows into the second stage, a doliolaria larva, characterized by a barrel-shaped body with three to five rings of cilia. The doliolaria settles on a substrate and develops into the third (and final) pentaradial stage, the pentacularia larva, which bears tentacles, just like adults. Finally, the pentacularia develops into a juvenile, which later develops tube feet and a complete digestive system.

Some sea cucumbers, like those in the genera Holothuria, reproduce asexually through binary fission. In this process, an individual splits into two parts, each of which develops into a complete organism.

Their natural predators include large mollusks, such as the giant tun (Tonna galea) and the partridge tun (Tonna perdix). They are also preyed upon by crustaceans, like crabs, lobsters, and hermit crabs, as well as some fish, like triggerfish and pufferfish.

Humans feed on these echinoderms, treating them as a delicacy, especially in countries like China, Korea, Japan, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The earliest sea cucumber fossils date back to the Ordovician Period, around 450 million years ago.

Since sea cucumbers feed on sediment detritus, they play an important role in breaking down organic matter, thereby recycling nutrients and maintaining the health of the ecosystem. Moreover, as plankton feeders, they filter oceanic water, prevent algal bloom, and reduce the acidification of water.