Starfish, also called sea stars, are echinoderms that constitute the class Asteroidea. As their name suggests, they have a characteristically star-like body, with most species having five arms radiating from a central disc (pentaradial symmetry). As echinoderms, they possess a network of fluid-filled channels, the water vascular system, which aids in locomotion, feeding, respiration, and sensory perception. They are benthic animals that crawl on the ocean floor using specialized tube feet.

Most species have a unique ability to evert their stomach through their mouth and digest their prey externally. Some starfish also possess remarkable regenerative abilities, often regrowing an entire body from a single arm.

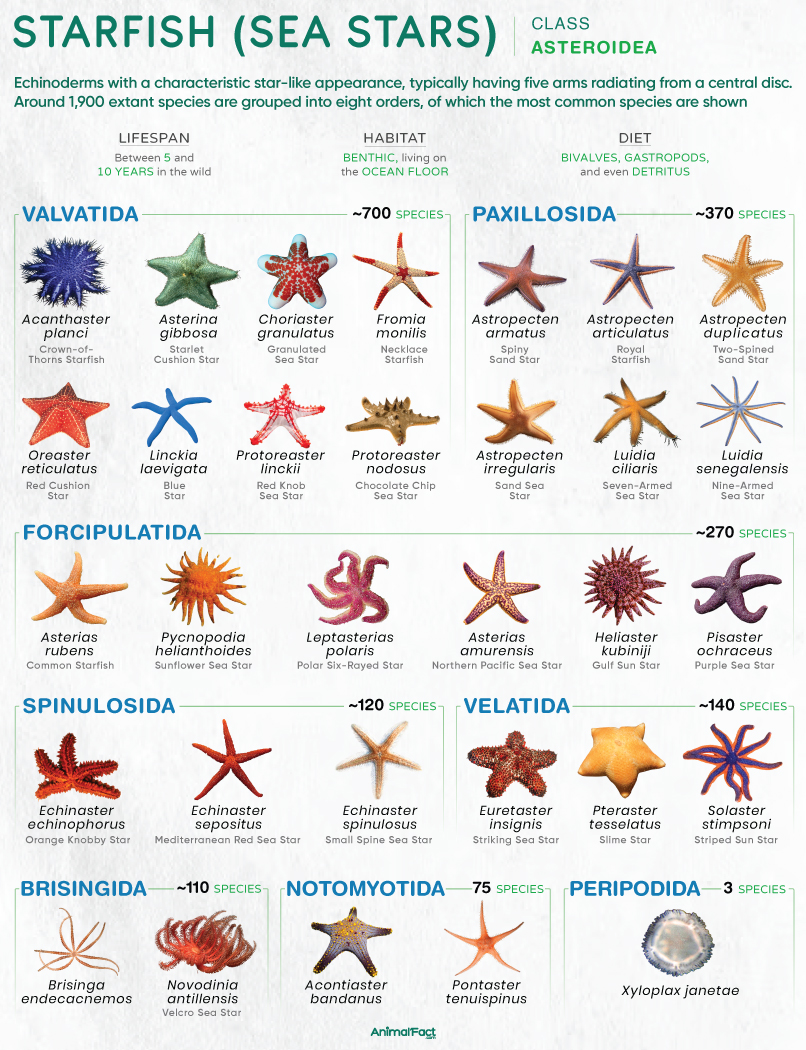

There are around 1,900 living species of starfish found in marine waters worldwide.

Although the size varies with species, on average, starfish typically measure about 5 to 10 in (13 to 25 cm) across from arm tip to arm tip. However, the largest recorded species, according to the Guinness World Records, is Midgardia xandaros, a specimen of which measured 4 ft 6 in (1.38 m) from tip to tip. Other large species include the sunflower sea star (Pycnopodia helianthoides), which has a maximum arm span of 3.3 ft (1 m).

The smallest starfish, Parvulastra parvivipara, grows to a diameter of only about 0.4 in (1 cm).

Most species exhibit a pentaradial symmetry, with five arms radiating from a central disc. However, the number of arms varies with species. For instance, the seven-armed sea star (Luidia ciliaris) has seven arms, while the sunflower sea star has over fifteen arms. In the Antarctic sun starfish (Labidiaster annulatus), the arms may be over fifty in number.

Starfish have their mouth on the ventral (oral) side of the body, while the anus lies on the dorsal (aboral) side. Their bodies are covered by a thin cuticle, followed by an epidermis and a dermis. The dermis comprises an endoskeleton made of calcified honeycomb-like structures called ossicles. Members of the order Paxillosida, in particular, have umbrella-like ossicles called paxillae, which form a false cuticle over the aboral surface, protecting soft tissues inside their bodies. Similarly, some orders, such as Valvatida and Forcipulatida, possess pincer-like ossicles called pedicellariae, which help grasp and remove small organisms or capture prey.

This is a hydraulic system comprising a network of fluid-filled canals. Water enters the system through a porous sieve-like ossicle on the aboral surface known as the madreporite. This opening leads to the stone canal, which in turn, connects to a ring canal encircling the mouth. The ring canal radiates a set of radial canals, with each radial canal running along the ambulacral groove in each arm. Short, lateral canals emanate from each radial canal, leading to bulbous structures called ampullae. These structures connect to tube feet (podia) through short linking canals. In most species, there are two rows of tube feet in each arm, running along the ambulacral groove on the oral surface.

Though the water vascular system serves the primary circulatory function, starfish also have a hemal system comprising a network of hemal sinuses and canals. The vessels of the hemal system form three distinct rings: the hyponeural hemal ring (around the mouth), the gastric ring (around the digestive system), and the genital ring (near the aboral surface). The three rings are connected by a vertical channel called the axial vessel. At the tip of this channel lies the highly vascularized organ (axial organ), which likely regulates flow between hemal channels.

Gaseous exchange typically occurs through thin, finger-like projections of the body wall known as papulae or skin gills. These projections appear as bulges along the aboral surface of the arms and help transfer oxygen to the coelomic fluid.

The mouth, located on the underside of the body, is surrounded by a tough peristomial membrane and is controlled by a sphincter muscle. It leads to a short esophagus, which connects to the stomach. The stomach has two parts: an eversible cardiac region and a smaller pyloric region. The pyloric part is associated with glands that secrete digestive enzymes.

A short intestine leads to the rectum and the anus, which open at the apex of the aboral surface of the disc.

Starfish are ammonotelic, meaning their primary nitrogenous waste product is in the form of ammonia. This gas diffuses through their tube feet, papulae, and other thin-walled areas of the body. Moreover, their coelomic fluid contains specialized phagocytic cells called coelomocytes that engulf waste material.

Although starfish do not have a centralized brain, they possess a complex nervous system. At the core of this system is a nerve ring surrounding the mouth, from which radial nerves extend into each arm. The radial nerves run along the ambulacral grooves, parallel to the radial canals.

The tube feet, spines, and pedicellariae of starfish are sensory in function, helping respond to physical contact or pressure. Moreover, the end of each arm bears eyespots, each comprising 80 to 200 simple eyes or ocelli that help detect light. Additionally, photoreceptor cells are scattered in other parts of the body.

The name Asteroidea comes from the Greek words aster, meaning ‘star,’ and eidos, meaning ‘form’ or ‘appearance.’ It was first introduced by the French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1830.

Around 1,900 living species of starfish are divided into 8 orders.

Fossil records of these echinoderms are sparse since their hard skeletal components tend to disintegrate after death. The oldest starfish-like fossil, Cantabrigiaster Fezouataensis, dates back to the Ordovician Period (around 480 million years ago).[1] During the two major extinction events of the Late Devonian and Late Permian, many then-existing starfish species went extinct. However, between the beginning and middle of the Middle Jurassic Period, they diversified rapidly.

These echinoderms are found exclusively in marine waters worldwide, from the poles to the tropics. While many species, such as the common starfish, are found in shallow, intertidal waters, others, like the members of the genus Freyastera, are recorded at depths as low as 6,000 m (20,000 ft).[2][3]

They are primarily benthic, living on, in, or near the ocean bottom.

Most species are carnivores, feeding primarily on small invertebrates, including bivalves and snails, whereas others, such as the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), feed on coral polyps. Some species, such as the sand star (Archaster typicus), are detritivores that consume decomposing organic matter.

The larvae of the crown-of-thorns starfish have been reported to absorb dissolved organic compounds, such as amino acids, from seawater, especially when particulate food is scarce.[4]

The lifespan of these echinoderms varies with species. While most survive between 5 and 10 years in the wild, some, like the purple sea star (Pisaster ochraceus), live as long as 34 years.[5]

Most species are gonochorous, having separate male and female sexes. A few species, such as Cryptasterina hystera, are simultaneous hermaphrodites, with each individual having a single reproductive organ, the ovotestis, that produces both eggs and sperm.[6] Others, like the starlet cushion star (Asterina gibbosa), are sequential hermaphrodites that start their life as males but later switch to females with age.[7]

They typically release their gametes into the surroundings through gonoducts located on the central disc between the arms, and as a result, fertilization is external. However, in some species, such as Cryptasterina hystera, fertilization is internal, and the embryo develops internally within the parent’s ovotestis. Although starfish do not typically brood their eggs, those that do (like Leptasterias hexactis) retain their eggs on the oral or aboral surface in a protective structure formed by curving their arms. These brooding species have lecithotrophic or yolky eggs, which develop directly into juveniles without an intervening larval stage.[8]

Through rapid mitotic divisions, the zygote transforms into a blastula. The blastula gradually undergoes gastrulation, forming the three germ layers. With time, the mouth and anus form through cellular invaginations. The archenteron connects to the mouth and forms the gut. A band of cilia develops on the exterior, which eventually extends onto two developing arm-like outgrowths, forming the bilaterally symmetrical, free-swimming bipinnaria larva. This larva uses the cilia for locomotion and feeding on plankton.

The bipinnaria develops three short ventral-anterior arms with adhesive tips and a surrounding sucker, forming the second larval stage, the bilaterally symmetrical brachiolaria larva. On completing its development, this larva anchors itself to the seabed with a short stalk made from the ventral arms and sucker.

With time, the brachiolaria develops an oral surface on the left and an aboral surface on the right side of the body. Due to internal rearrangements, the mouth and anus shift to new positions. Some cavities disappear, but others form the water vascular system and the visceral coelom. In this process, the larva attains a pentaradial symmetry, loses its stalk, and becomes a free-living juvenile starfish.

Although most species reproduce sexually, some do so asexually, either by fission of their central discs (as in the blue spiny starfish, Coscinasterias tenuispina) or by autotomy of one or more of their arms (as in Guilding’s sea star, Linckia guildingi).[9][10]

The larvae of some starfish, such as those of the genus Luidia, reproduce asexually by autotomizing parts of their bodies or through budding, forming genetically identical clones (larval cloning).[11]

They are typically preyed upon by crustaceans, like crabs and lobsters, as well as gastropods, including whelks and tritons. Some fish, such as triggerfish, pufferfish, and boxfish, also feed on starfish. When these echinoderms are exposed during low tide, seagulls often feed on them.

Juveniles of some species, like the Forbes’ sea star (Asterias forbesi), may eat each other (cannibalism), primarily to reduce competition and gain easy access to nutrition.[12]