Stoneflies are insects that belong to the order Plecoptera. The name ‘Plecoptera’ stems from the Ancient Greek words plekein, meaning ‘braid’, and pteryx, meaning ‘wings’. This taxonomy refers to the complex, braid-like pattern of venation on the two pairs of wings on their thorax. These insects also possess two long appendages called cerci at the tip of their abdomen.

They are hemimetabolous insects, developing from eggs to adults through nymphs instead of a pupal stage. The nymphs typically live under rocks and pebbles in clean, freshwater environments, such as rivers and streams with swift currents. Once the nymphs molt into adults, they become terrestrial, surviving only for a few weeks.

Since stonefly nymphs are highly sensitive to pollution, their presence serves as an important bioindicator of water quality.

They measure around 0.25 to 2.5 in (6 to 66 mm).[1]

As insects, stoneflies have the basic three-part body plan, comprising three segments: the head, thorax, and abdomen.

The head bears a pair of multi-segmented antennae and simple mouthparts with chewing-type mandibles. This segment also has a pair of large compound eyes, as well as two or three simple eyes (ocelli).

The thorax bears three pairs of segmented legs. In nymphs, the last segment of the legs (tarsi) end in claws, which help them anchor to the substrate and prevent being washed away by currents. These claws are present in adults, too, though they are less developed.

The two pairs of membranous wings are also located in the thoracic region. While the forewings are long and narrow, the hindwings are broader and fan-shaped. These wings lie flat over the body when at rest, often overlapping each other.

The abdomen has 10 externally visible abdominal segments, at the tip of which are two long and filamentous appendages called cerci.

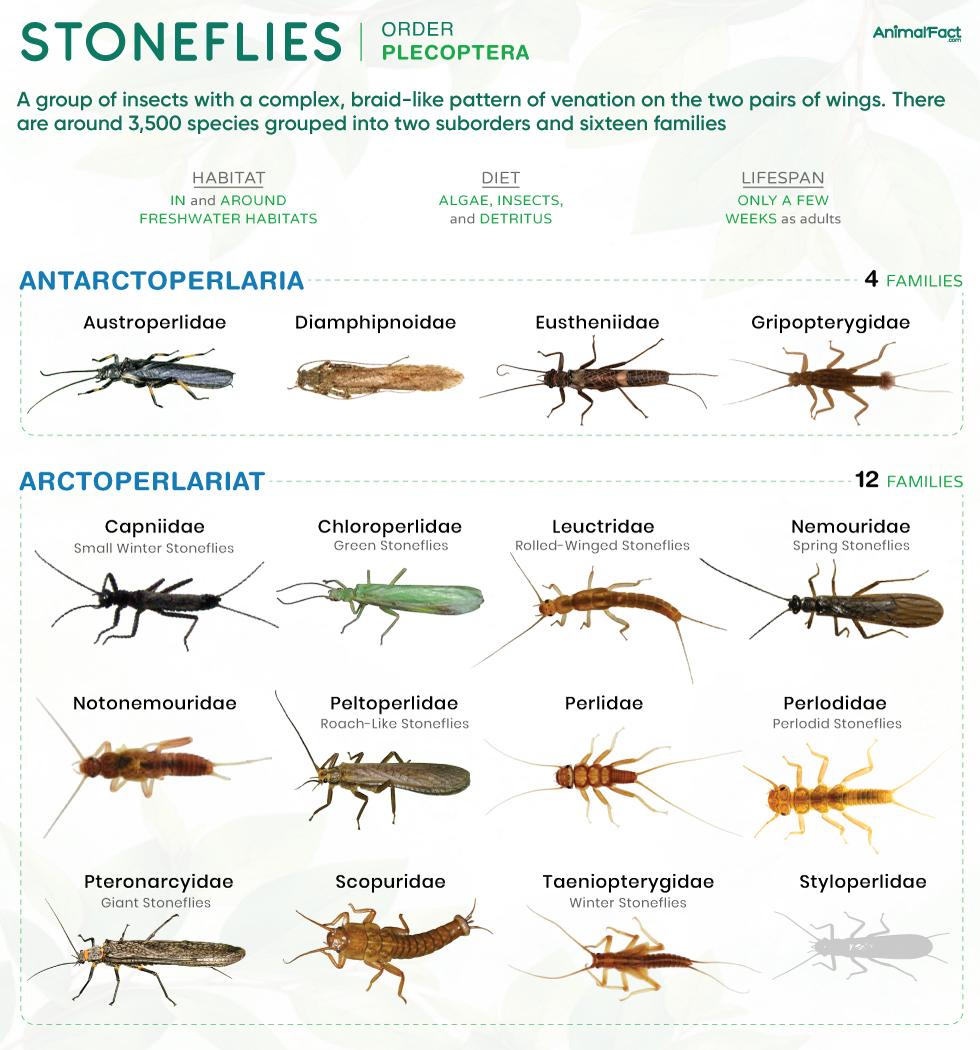

Around 3,500 species are divided into 2 suborders and 16 families.

These insects are found on all continents except Antarctica.

The nymphs are fully aquatic, found at the bottom of clean freshwater bodies, typically streams, rivers, springs, and occasionally lakes.[2] They live under rocks, pebbles, and in leaf litter or woody debris.

Adult stoneflies are terrestrial but remain very close to water bodies. Being weak-fliers, they perch themselves on rocks, stones, and vegetation. However, the Lake Tahoe benthic stonefly (Capnia lacustra) is currently the only known species that is fully aquatic throughout its entire life cycle, including the adult stage.

Adults of most species have vestigial mouthparts and do not feed. They rely on stored energy from their nymphal stage. However, some species of the family Taeniopterygidae consume algae or lichens as adults.[3]

Nymphs are active feeders, with their diet varying by species, size, and developmental stage. In most species, young nymphs feed on particulate organic matter, decaying vegetation, and vegetable components such as diatoms and algal fragments. However, with age, they switch to predominantly carnivorous diets. For instance, well-developed nymphs of the species like Hemimelaena flaviventris and Perla marginata feed on insect larvae.[4]

A few species, like Capnia nigra, remain herbivorous throughout their lives.

Adult stoneflies survive only for a few weeks.

Male stoneflies attract the females by drumming or tapping their abdomens on rocks or logs. If the female reciprocates, the pair mates, and the male transfers a packet of sperm (spermatophore) to her.

The female either flies over the water surface to drop her eggs, or may hang on a rock or branch to lay eggs on the water. A single female can lay hundreds to thousands of eggs, depending on the species. The eggs are covered in a sticky coating, which helps them stick to the surface of rocks underwater, keeping them from being swayed by currents.

In about 2 to 3 weeks, the eggs hatch into nymphs, which resemble wingless adults. However, some stoneflies, such as winter stoneflies, undergo diapause, hatching with late winter or early spring snowmelt.[5]

Depending on the species, nymphs obtain oxygen either by diffusion through their exoskeleton or through external gills. For 1 to 4 years, they undergo 12 to 36 molts before reaching adulthood. When they are ready to molt, the nymphs leave the water and climb onto a rock or other stable surface. They then finally shed their exoskeleton and become adults.

The aquatic nymphs of stoneflies are particularly vulnerable to predation by fish, including trout, salmon, and sunfish. Other common predators of the nymph stage include dragonfly nymphs, predaceous water beetles, and dobsonfly larvae (hellgrammites).

Adult stoneflies, on the other hand, are often eaten by insectivorous birds such as swallows and flycatchers. Amphibians like frogs and salamanders may feed on both nymphs and adults.