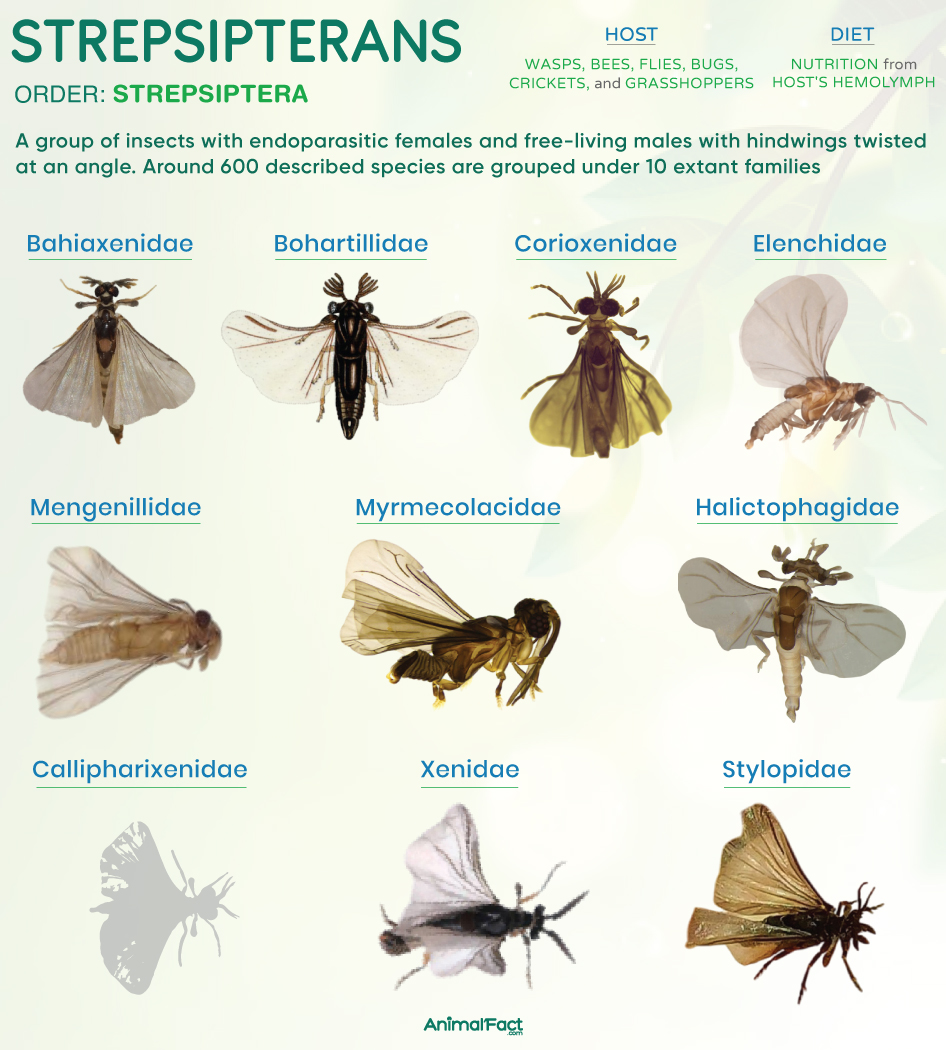

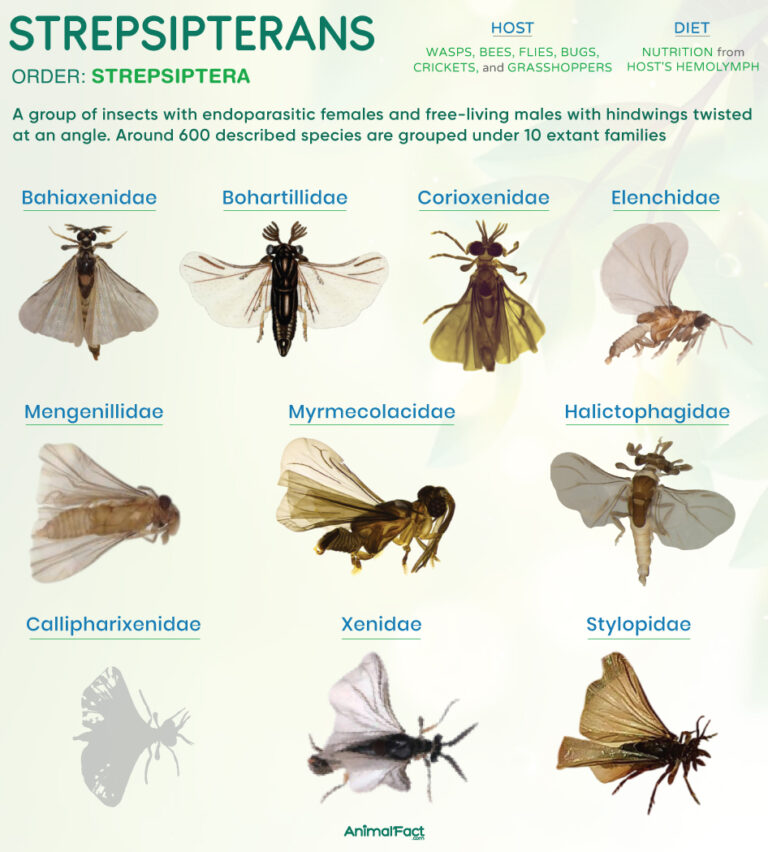

Strepsipterans, also known as twisted-wing insects or twisted-winged parasites, are members of the insect order Strepsiptera. They exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism, with the females being wingless, larva-like, and completely endoparasitic, while males are short-lived, free-living, and fully winged. The hindwings of the males rest at a distinctive twisted angle, a feature that inspired the common name of these insects.

Depending on the species, the females parasitize a wide range of hosts, including bees, wasps, ants, cockroaches, crickets, grasshoppers, and silverfish, among others.

These insects are also notable for the hypermetamorphosis of their larvae. Their newly hatched larvae are mobile and seek out a host, but once inside, they transform into sedentary forms, which undergo multiple molts before reaching maturity.

Adult strepsipteran males are typically 0.04 to 0.28 in (1 to 7 mm) long, while females are 0.08 to 1.18 in (2 to 30 mm). Their larvae are around 0.0007 in (0.0178 mm) long.[1][2]

The morphology of these insects varies considerably among males and females.

The bodies of male strepsipterans are divided into head, thorax, and abdomen. The head bears large eyes that, unlike the thousands of ommatidia found in the eyes of most insects, consist of only a few dozen eyelets capable of forming a complete image. These eyelets are separated by cuticle and confer the eyes a distinctive, berry-like appearance.

They also have a pair of sensory, flabellate antennae, in which each segment bears a thin, flat process that projects outward.

The thorax is subdivided into three segments: the pro-, meso, and metathorax, each bearing a pair of legs. The prothorax is small, while the mesothorax and metathorax are highly developed to support flight. The forewings of the mesothorax are reduced to club-like balancing organs called halteres, whereas the fan-shaped hindwings are large and membranous, helping the males fly and seek mates.

The abdomen bears 10 to 11 telescopic segments, which provide flexibility when the male bends to mate with a female embedded in a host. The genital capsule at the tip of the abdomen bears the male copulatory organ, the aedeagus.

They have a well-sclerotized cephalothorax (fused head and thorax). In most species, the females lack wings, legs, and eyes. However, those in the family Mengenillidae are free-living and possess legs and small eyes.

The name of the order, coined by the English entomologist William Kirby in 1813, is derived from the Ancient Greek words strépsis (turning around) and pterón (wing). This taxonomy hints at the twisted form of the hindwings of the males when at rest.

Around 600 described species are grouped under 10 extant families.

Recent phylogenetic studies indicate that strepsipterans are most closely related to beetles, and together they form the group Coleopterida.[3] According to estimates, beetles and strepsipterans diverged around 300 to 350 million years ago.

These insects parasitize a range of hosts, including grasshoppers, crickets, silverfish, bugs, flies, praying mantises, cockroaches, bees, wasps, and ants. In the family Myrmecolacidae, males parasitize ants, whereas females develop inside grasshoppers or crickets. Similarly, members of Mengenillidae parasitize only silverfish, while those of Stylopidae specialize exclusively in bees.

Adult males lack functional mouthparts and do not feed at all. The females, on the other hand, absorb nutrients directly through their body wall from the host’s hemolymph.

The larvae, particularly the later instars, feed on the host’s tissues and hemolymph.

Male strepsipterans are extremely short-lived, surviving typically for 3 to 4 hours to seek a mate and inseminate it.[4] In contrast, the lifespan of females is intricately linked to that of their host’s. For example, Xenos vesparum, which parasitizes the European paper wasp (Polistes dominula), can persist within its host over winter, surviving for at least 9 to 10 months or longer.[5]

The females, while remaining within the host’s body, typically release pheromones, which the males detect and are attracted to. The anterior end of the female’s cephalothorax protrudes slightly from between the host’s abdominal segments. In most species, the male transfers sperm through a slit in the female’s protruding body part, but it never enters the host (traumatic insemination).[6]

The fertilized eggs hatch into first instar planidium larvae within the female’s body. These larvae have legs and single-lens ocelli called stemmata. They are highly active and move around freely within the female’s hemocoel, drawing nutrients from the body fluid (hemocoelus viviparity).

The planidium larvae are capable of seeking new hosts. Thus, they emerge from the host’s body through the brood canal on their mother’s head. On latching onto a suitable host, the larva secretes enzymes that soften the cuticle (particularly on the abdomen) and make way for it to enter. Once the larva invades the host’s body, it undergoes hypermetamorphosis through which it loses its legs and becomes less mobile. It induces the host to produce a bag-like structure within which it feeds, grows, and undergoes four more instars.

Larvae that undergo pupation after the final molt develop into males, forming wings and large compound eyes before emerging from the host’s body. In contrast, larvae that do not pupate remain in a neotenic, larva-like form, becoming females that stay within the host.

Since these insects spend most of their life hidden inside their hosts, they have very few documented predators. The free-living males, which briefly emerge to fly and mate, may be eaten opportunistically by small birds, lizards, and other insectivorous vertebrates. Additionally, some generalist insect predators, such as spiders, mantids, ants, assassin bugs, and robber flies, may consume them.

If the host insect is consumed by a predator or attacked by a parasitoid, the strepsipteran is incidentally killed.