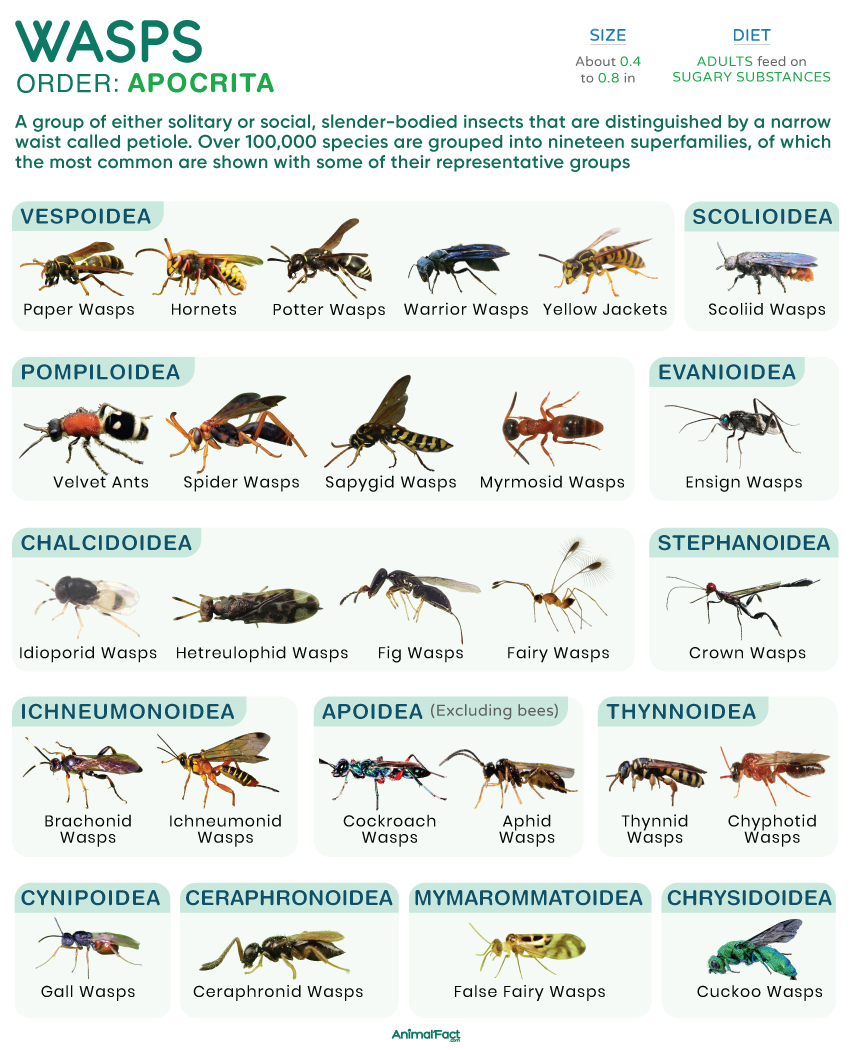

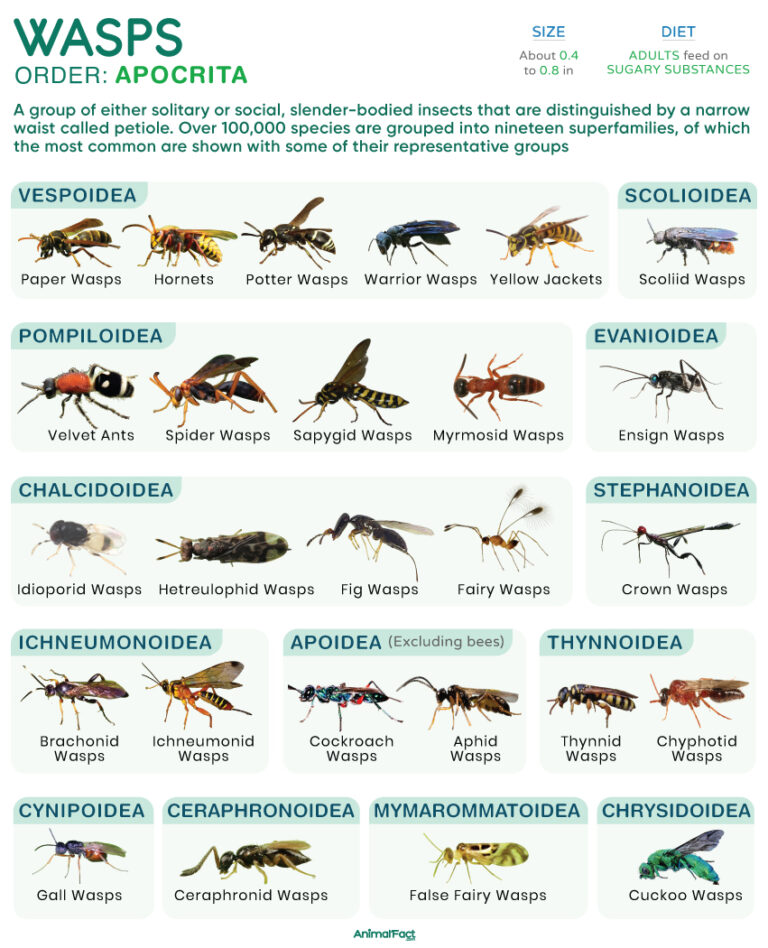

A wasp is any insect that belongs to the suborder Apocrita within the order Hymenoptera, excluding bees and ants. Unlike bees, which are generally stocky and covered with hair, wasps possess slender, elongated bodies with a characteristic narrow waist (petiole).

These insects are either solitary or social. While social wasps live in well-coordinated colonies, solitary ones are typically parasitoids that lay their eggs within the bodies of hosts. Adults primarily feed on nectar and sugary substances, whereas their larvae usually consume insect prey provided by the mother. Though less efficient than bees, some wasps inadvertently end up transferring pollens.

One of the most diverse insect groups, over 100,000 known species of wasps are found worldwide, except in polar regions.

On average, most wasps measure about 0.4 to 0.8 in (1 to 2 cm).

One of the largest species, the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia), is up to 2 in (5 cm) long.[1] Females of the long-tailed giant ichneumonid wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus) possess a long ovipositor which, together with the body, measures over 5 in (13 cm).[2]

The world’s smallest known insect, Dicopomorpha echmepterygis, also happens to be a member of the wasp family Mymaridae (fairyflies). It has an average body length of only about 0.0073 in (186 μm).[3][4]

Like other insects, wasps have a tripartite body plan, with their bodies divided into three broad segments: head, thorax, and abdomen. The body is encased in a chitinous exoskeleton.

The head bears a pair of compound eyes, typically three simple eyes (ocelli), and a pair of segmented antennae. Their mandibles are adapted for biting and cutting, while their labium and maxillae form an extendable tongue-like organ used to lap up nectar and other liquid food sources.

The thoracic region is subdivided into three parts: the pro-, meso, and metathorax, with each part bearing a pair of legs. The mesothorax and the metathorax bear the forewings and the hindwings, with the forewings being larger than the hindwings. The leading edge of the hindwings bears small, curved, hook-like structures called hamuli, which help couple the hindwings to the forewings during flight.

They typically possess 11 abdominal segments. However, the first segment (known as the propodeum) is fused with the metathorax, while the second segment forms a waist-like petiole. The thorax and the propodeum are collectively referred to as the mesosoma.

The remaining abdominal segments (3 to 7 or 8) form the gaster, which, along with the petiole, is collectively known as the metasoma. The last segment is typically reduced, ending in a pair of claspers in males and an ovipositor in females.

Wasps represent a paraphyletic group within the suborder Apocrita, excluding bees (clade Anthophila) and ants (family Formicidae). All species are grouped into 19 superfamilies.

*Excluding bees

The earliest confirmed wasps first appeared in the Jurassic Period (200 to 145 million years ago), most likely from the sawflies (suborder Symphyta), and later diversified during the Cretaceous Period.

These insects have a worldwide distribution except in the polar regions, with the highest species diversity in the tropics. For example, the Afrotropical region alone hosts over 15,500 species of Darwin wasps (family Ichneumonidae).[5]

Various wasps occupy different habitats. For instance, European wasps inhabit cavities in ceilings, logs, tree trunks, soil, or underground.[6] In contrast, paper wasps live in both urban and natural environments, occupying nests made of paper-like, chewed wood fiber (hence their name).[7] Others, such as cuckoo wasps, prefer open, sun-exposed habitats such as dry meadows and sandy areas.[8]

The diet of wasps varies with species and the life cycle stage. Adults typically feed on sugary substances, such as nectar, fruit juices, honeydew, and even human food like soda and candy.

Some wasps, such as yellowjackets, occasionally feed on tree sap, as well.[9]

Since larvae require protein for growth, they usually feed either on pre-chewed insects, such as flies, caterpillars, spiders, crickets, and even bees (for social wasps) or paralyzed insects (for solitary wasps). However, pollen wasps feed their larvae pollen and nectar.

The larvae of parasitoid wasps feed on the host insect. They first consume non-vital tissues like fat bodies, hemolymph, or muscles, and later the vital organs, eventually killing the host. However, adult parasitoid wasps, like non-parasitoids, feed on sugar-rich resources.

Most wasps are diurnal, being active during the day and resting at night.

Most wasps are solitary and do not form colonies. The females build their nests, forage alone, and feed their offspring. Many groups, such as digger wasps (genus Sphex), dig ground burrows and fill them with insects for their larvae to eat. Others, like mud daubers and pollen wasps, build cells or tubes in sheltered places by collecting mud pellets and shaping them. Similarly, potter wasps construct vase-like nests against walls or tree twigs.

Most solitary wasps are parasitoids, laying one or more eggs on host insects, such as beetles, caterpillars, horntails, and aphids. When the eggs hatch, the larvae feed on the host’s tissues.

Only wasps in the family Vespidae (particularly the subfamilies Vespinae and Polistinae) are eusocial, just like bees and ants. They form organized colonies with a distinct caste system, comprising a queen (reproductive female), workers (sterile females), and, seasonally, drones (males). While the queen lays eggs, the workers forage, build nests, and defend the colony. Multiple generations live together in the same colony.

Most social wasps build their nests using some form of plant fiber, especially wood pulp, which they mix with other plant secretions, along with saliva. They construct multiple brood cells in the pattern of a honeycomb, encased in a large, protective envelope. Although most species build multiple combs, a few, such as Apoica flavissima, have a single comb.

Cuckoo wasps (family Chrysididae) exploit the parental care of other wasps by laying their eggs in the hosts’ nests. Similarly, sand wasps of the genus Ammophila may parasitize the nests of their own species, sometimes by removing the resident female’s egg and substituting it with their own.

Social wasps are highly aggressive and defensive because they must protect their nest, brood, and queen. When threatened, they sting predators and release alarm pheromones that rally nearby workers. In contrast, solitary wasps usually use their sting only to paralyze prey.

Solitary wasps typically live much shorter lives compared to social wasps. Their females survive for several weeks to a few months, while the males generally live just a few weeks simply to mate.

In social wasps, adult workers usually survive for 12 to 22 days, while drones live slightly longer, about 15 to 25 days. The queens have the longest lifespan, often reaching up to a year.[10]

Depending on the species, wasps can survive a few days to several weeks without food.

Most solitary wasps emerge from their cocoons in spring or early summer. Males typically appear a little earlier and wait for the females to emerge. Soon after the females emerge, the males court them, mate, and often die shortly afterward. The sperm is stored in the female’s body, and it is eventually used to fertilize the eggs.

After fertilization, the females seek suitable sites to lay their eggs. However, before egg-laying, they typically provision the nests with adequate paralyzed insects. They then lay their eggs and seal the cells with soil, plant fibers, or mud for protection. Unlike social wasps, which exhibit parental care, mothers of solitary wasps leave the cells and typically do not return to nurse.

The eggs typically hatch into soft-bodied larvae within 2 to 6 days. These larvae undergo 4 to 5 molts within 1 to 3 weeks, growing in size with each molt. When the larva is mature, it spins a silk-like cocoon around itself, transforming into an immobile pupa. Within this cocoon, its body tissues disintegrate, and adult structures, like wings, legs, and antennae, begin to develop. Depending on the species, the pupal stage lasts for a few days, several weeks, or even months before the adult emerges. In temperate regions, many solitary wasps overwinter as pupae, emerging as adults during spring.[11]

In social wasps, the fertilized queen starts a nest in spring, laying the first eggs that develop into workers. As more workers emerge, they take over the responsibilities of nest building, foraging, and larval care from the queen. As the colony matures, the queen produces males (usually in late summer to early autumn) and new queens.

When laying eggs, female wasps can choose whether to release the sperm stored in their body for fertilization (a system called haplodiploidy). If sperm is released, the egg gets fertilized and develops into a diploid female (2n). If sperm is retained, the egg remains unfertilized and develops into a haploid male (n). Thus, in both solitary and social wasps, females have active control over the sex of their offspring.

They are preyed upon by a range of animals. For instance, their most common predators are certain birds, such as bee-eaters (specialized feeders of adult wasps) and woodpeckers (commonly raid wasp nests for larvae). The Asian giant hornet is primarily preyed upon by the bird honey buzzard.

Among mammals, bears, skunks, badgers, and raccoons target wasp nests.

Some insects, such as praying mantises, dragonflies, and robber flies, also consume adult wasps. Additionally, wasps often end up in the webs of orb-weaving spiders and form a common part of their diet.