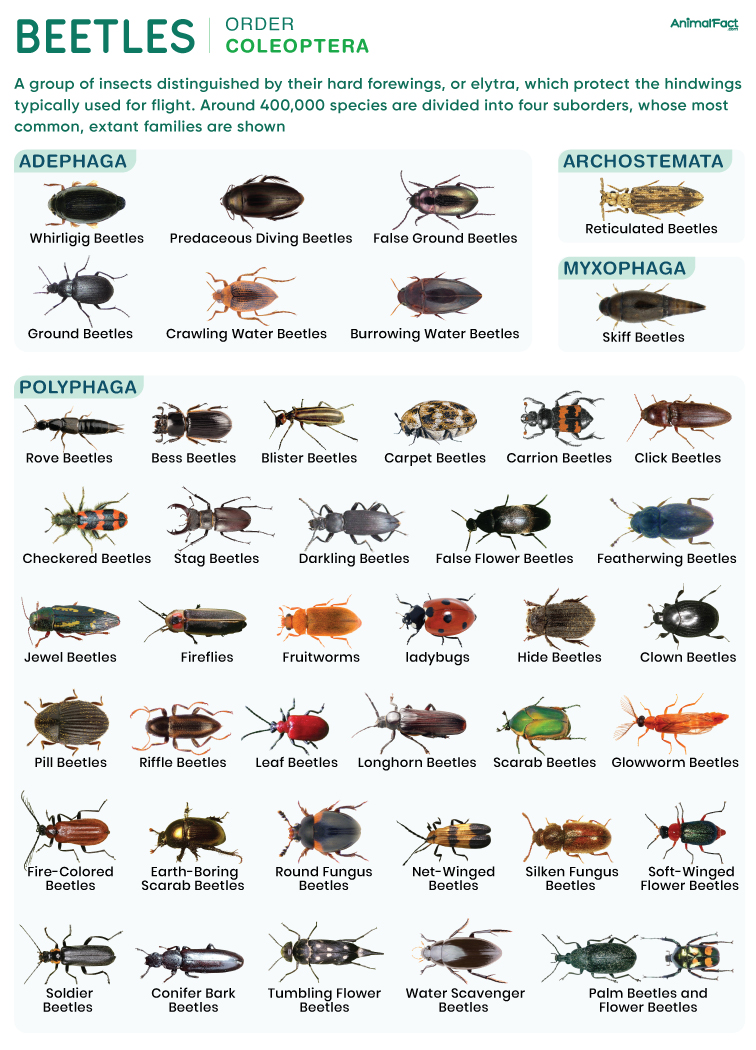

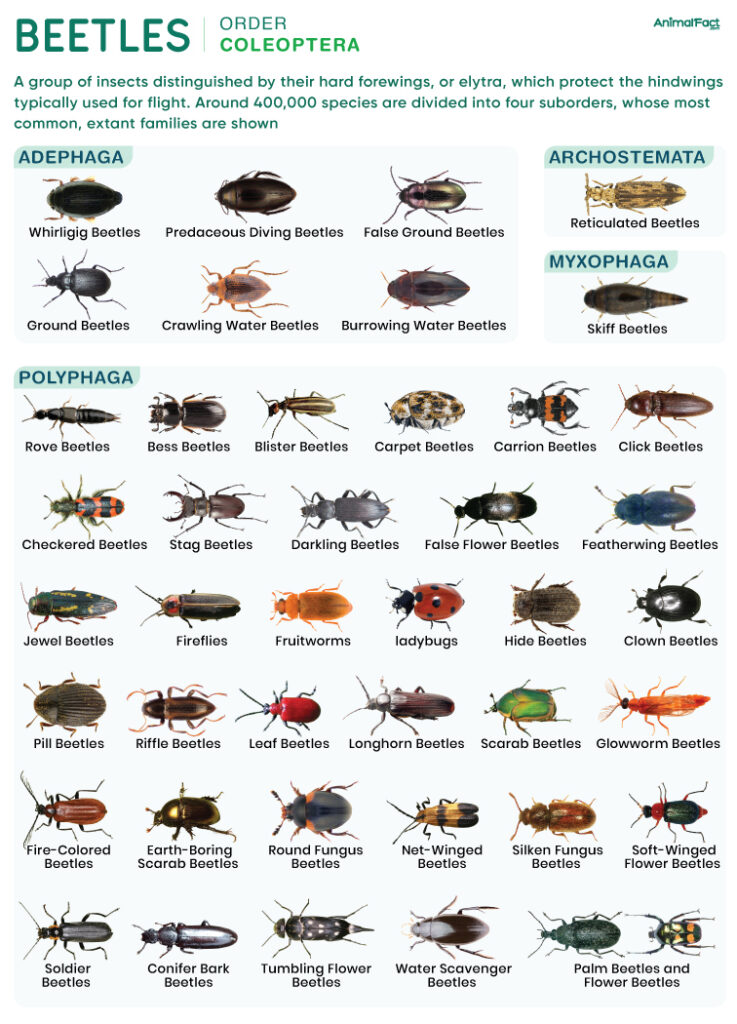

Beetles are members of Coleoptera, the largest order of insects. There are around 400,000 described species of beetles, representing around 40% of all known insect species and 25% of all known animal species. They are easily recognized by their hardened forewings or elytra, which cover the hindwings that are typically used for flight.

They occupy almost all habitats, except strictly marine and polar regions. Their diets vary widely depending on the species, with some feeding on plants, dung, or decaying animals, while others consume fungi, natural fibers, or even other insects.

The longest species, the Hercules beetle (Dynastes hercules), measures up to 7.4 in (19 cm) in length, whereas the shortest, the featherwing beetle (Scydosella musawasensis), is as little as 0.012 in (325 μm).[1]

The full-grown larva of the actaeon beetle (Megasoma actaeon), which happens to be the heaviest insect larva, weighs about 8 oz (228 g).[2] Similarly, the heaviest adult beetles are the males of goliath beetles (Goliathus), which weigh 2.5 to 3.5 oz (70 to 100 g).

Like all insects, beetles have a tripartite body plan, with their bodies divided into three broad segments: head, thorax, and abdomen. The body is covered by a particularly hardened exoskeleton composed of chitin.

The head bears a pair of antennae, a pair of compound eyes, and the mouthparts. The antennae vary greatly in shape, ranging from clubbed, thread-like, comb-like, toothed, or angled, depending on the species.

Most species bear 11 segments on their antennae. The first segment, known as the scape, attaches to the head and is often enlarged, whereas the second segment, the pedicel, contains sensory structures like the Johnston’s organ. The remaining segments are collectively referred to as the flagellum. In some species, such as the scorpion beetle (Onychocerus albitarsis), the antennae bear specialized venom-injecting structures, which help poison their predators.[3]

They have a pair of hard, tooth-like mandibles that move horizontally, helping grasp, crush, and slash food or even predators. The males of stag beetles (family Lucanidae) have enlarged mandibles that they use to fend off other males. Additionally, most species possess two pairs of finger-like appendages, the maxillary and labial palpi, that help move the food into the mouth. The mouthparts are enclosed in a plate-like structure called the clypeus.

The thoracic region is subdivided into two broad segments: the pro- and pterothorax (fused meso- and metathorax). The prothorax, encased in a shield-like plate called the pronotum, bears a single pair of legs, whereas the pterothorax bears two pairs of legs. While the prothorax lacks wings, the pterothorax bears both the forewings and the hindwings.

Each leg has five segments: coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, and tarsus. In most beetles, the tarsal segment bears a pair of claws for efficient attachment. Some water beetles, such as the predaceous diving beetles, have a modified third pair of oar-like legs with rows of long hairs that help in swimming.[4] Similarly, in ground beetles, the legs are wide and often spined, an adaptation that suits their fossorial lifestyle.

The forewings are modified into hardened, shell-like cases known as elytra. These cases cover the hind part of the body and protect the hindwings. However, in some beetles, like leatherwings (Cantharidae), the elytra are considerably soft. In some groups, such as stag beetles, the two elytra are fused to form a single, solid shield over the abdomen.

The hindwings are the real flight wings of beetles. These wings are crossed with veins that serve as folding points when the insect is at rest.

Most beetles possess 9 or 10 abdominal segments, of which only 5 to 8 are visible externally. Three different types of sclerites cover the abdominal region: tergites (dorsal), sternites (ventral), and pleura (lateral).

The abdomen houses the vital organs of the body, including the digestive and reproductive systems.

As insects, beetles have an open circulatory system, comprising a segmented tube-like vessel that functions as the heart. This vessel is attached to the dorsal wall of the hemocoel and helps pump hemolymph throughout the insect’s body.

They have a network of air-filled tubes called the trachea, which open to the exterior through small, paired openings called spiracles along the sides of the body.

When diving into water, predaceous diving beetles (Dytiscidae) carry an air bubble in specialized hydrophobic body hair or under their elytra. The bubble covers some of the spiracles and provides a store of air for the insect to breathe.

The digestive system comprises an alimentary canal that runs from the mouth to the anus. The canal is broadly divided into fore-, mid, and hindgut.

The foregut comprises the pharynx, esophagus, crop, and proventriculus. It is followed by the midgut, the primary site of digestion and absorption, and the hindgut, which includes the ileum, colon, and rectum. At the junction of the midgut and the hindgut lie four to six tubular structures, the Malpighian tubules, which help remove nitrogenous waste (mainly in the form of uric acid) from the hemolymph and dump it into the hindgut.

Beetles have a centralized nervous system that comprises a supraesophageal ganglion (functions as the brain) and a ventral nerve cord with segmental ganglia (typically three thoracic and six to eight abdominal ganglia). Each segmental ganglion gives rise to peripheral nerves that branch outward into the body.

The name Coleoptera was coined by Aristotle, derived from the Greek word koleopteros, which combines koleos (sheath) and pteron (wing). This naming hints at the hardened, shield-like forewings of beetles. On the other hand, the name ‘beetle’ derives from the Old English word bitela, which translates to ‘the little biter.’

They are divided into 4 extant suborders and 165 extant families, which are shown in the list below.

These insects first appeared in the early Permian Period (around 295 million years ago), with the earliest known genus, Coleopsis, unearthed in Germany. These early beetles were xylophagous, primarily boring into wood. However, they diversified into herbivorous and carnivorous forms during the Jurassic Period, coinciding with the rise of angiosperms.

Beetles are cosmopolitan, found almost everywhere on the planet, except on mainland Antarctica (though they inhabit subantarctic islands). However, remains of an extinct species, the Ball’s Antarctic tundra beetle (Antarctotrechus balli), have been unearthed from Antarctica’s Beardmore Glacier.[5]

These insects thrive in both terrestrial and aquatic environments, including freshwater and coastal habitats. They can be found in foliage, living among leaves, flowers, bark, galls, and even within decaying plant matter.

Their species diversity is the highest in tropical rainforests, though they also occupy temperate forests, grasslands, deserts, and even alpine zones.

Dietary choices vary considerably among the different groups of beetles. For instance, leaf beetles, as their name suggests, are herbivorous and primarily feed on the leaves of plants. Dung beetles are coprophagous, feeding on dung, whereas carrion beetles consume dead and decaying animals (necrophagy). Predatory beetles, such as ladybugs, ground beetles, and tiger beetles, hunt other insects and small invertebrates, while pleasing fungus beetles (family Erotylidae) specialize in eating fungi and fungal spores.[6]

The larvae of the varied carpet beetle (Anthrenus verbasci) feed on keratin and chitin of natural fibers, including wool, fur, hair, feathers, hides, horns, leather, and silk.[7] Others, like the larvae of parasitic flat bark beetles (Passandridae), are exclusively ectoparasitic on the immature stages of hymenopterans and other beetles.[8]

When a beetle is ready to fly, it raises its elytra and unfolds its hindwings, which are then powered by flight muscles in the thorax. Some species, such as some in Scarabaeinae, Curculionidae, and Buprestidae, fly with their elytra closed. Others, like many rove beetles, have greatly reduced elytra, and they mostly move on the ground rather than flying.

Most beetles release species-specific pheromones to communicate with their conspecifics. For instance, females of the oriental beetle (Exomala orientalis) release sex pheromones to attract mates.[9] Other species, such as the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata), release alarm pheromones that help alert other beetles in their surroundings.

Some beetles, such as larval Lucanus species, stridulate by rubbing their legs together. This behavior helps in spatial coordination among the larvae.[10]

Although a characteristic of hymenopterans, the beetle Austroplatypus incompertus exhibits obligate eusocial behavior.[11] Its colonies are formed by a single fertile female (the queen), who excavates galleries in living eucalyptus trees and initiates the cultivation of fungi. Her unfertilized daughters act as non-reproductive workers, maintaining the galleries and nursing their siblings. The males have a sole reproductive purpose, dying soon after mating.

The lifespan of these insects varies greatly with species. For instance, adult carpet beetles survive between 13 and 44 days, while the golden jewel beetle (Buprestis aurulenta) has been found to live up to 50 years under exceptional conditions, mostly as larvae inside wood.[12]

Most beetles reproduce sexually, in which the male transfers the sperm to the female to fertilize her eggs. Courtship varies among different groups. For instance, some scarab beetles, such as shining leaf chafers (subfamily Rutelinae), attract their mates using pheromones derived from fatty acid synthesis, whereas fireflies seek mates using their abdominal light-producing organs.

A male blister beetle (family Meloidae) resorts to tactile stimulation, climbing onto the female’s dorsum and tapping on her antennae, head, and palps with his antennae.

During mating, the male grips the female tightly and inserts his aedeagus (intromittent organ) into the female’s genital opening. Most females store the sperm in an internal organ called the spermatheca. They may store sperm from multiple males and selectively fertilize the eggs in the future. They then lay the fertilized eggs in a suitable environment.

They are holometabolous insects, meaning their eggs become adults through larval and pupal stages.

The eggs typically have soft, smooth surfaces, though those of the family Cupedidae have hard eggs. Depending on the extent of parental care to be provided, the number of eggs laid varies among different beetles. While some may lay only a dozen eggs (with high parental care), others may lay several thousand over their lifetime (minimal parental care).

The eggs hatch into larvae, which are typically voracious feeders. While leaf beetle larvae feed on plant surfaces, jewel beetles (Buprestidae) and longhorn beetles (Cerambycidae) are internal feeders, burrowing within wood or other substrates. Others, such as larvae of ground beetles, are predatory, just like their adult counterparts.

Beetle larvae are distinguished from those of other insects by their hardened, often dark heads, well-developed chewing mouthparts, and the presence of spiracles along the sides of their bodies.

Depending on the species, environmental conditions, and resource availability, larvae undergo 3 to 10 molts. In many species, the instars simply increase in size with each molt, but in others, more dramatic changes occur. For instance, in parasitic beetle families like Meloidae, Micromalthidae, and Ripiphoridae, the first instar (the planidium) is highly mobile and moves around in search of a host. In contrast, the late instars are sedentary and specialized for feeding and development within or on the host. Such a developmental process with morphologically and behaviorally varying instars is called hypermetamorphosis.

The length of the larval period varies greatly among beetle species. For example, members of the genus Anisotoma can complete their larval development within just two days when living in slime molds, while Trogoderma inclusum larvae may dramatically extend this stage under stressful conditions, with one individual surviving for up to 3.5 years in isolation.

A drop in juvenile hormone (JH) levels triggers the transformation of larva to pupa. The larva stops feeding, becomes less active, and seeks a secure place to settle in. It develops wing buds and darkens as it matures. Most pupae are exarate, with appendages that are not attached to the body. However, some families, such as Staphylinidae and Ptiliidae, are obtect, with appendages fused with the body.

In some groups, such as skin beetles, the pupa is enclosed in a cocoon composed of shed larval skins (exuviae) and silk-like material.

Under the influence of the ecdysone hormone, the pupal cuticle starts to rupture, and the adult gradually emerges. The adult pumps hemolymph into its wings to fully expand them for the first time, while the exoskeleton hardens and gradually darkens in color.

Beetles have a wide range of predators. Several birds, such as sparrows, wrens, thrushes, warblers, woodpeckers, robins, crows, and blue jays, feed on them. Similarly, small to medium-sized mammals, such as shrews, moles, skunks, raccoons, and bears, consume beetles, particularly their larvae, in soil or wood. Moreover, frogs and lizards also feed on these insects.

Other arthropods, like ants, consume beetle eggs and larvae, whereas spiders and praying mantises feed on adult beetles. Others, such as scoliid wasps (Scoliidae), are parasitoids of scarab beetle larvae.[13]