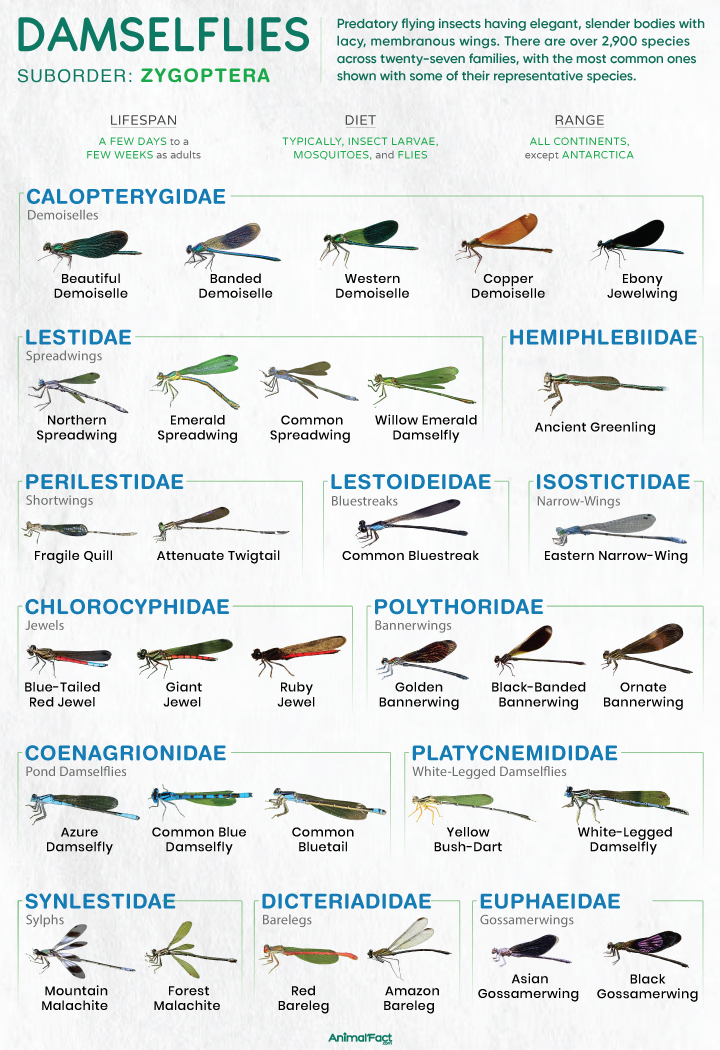

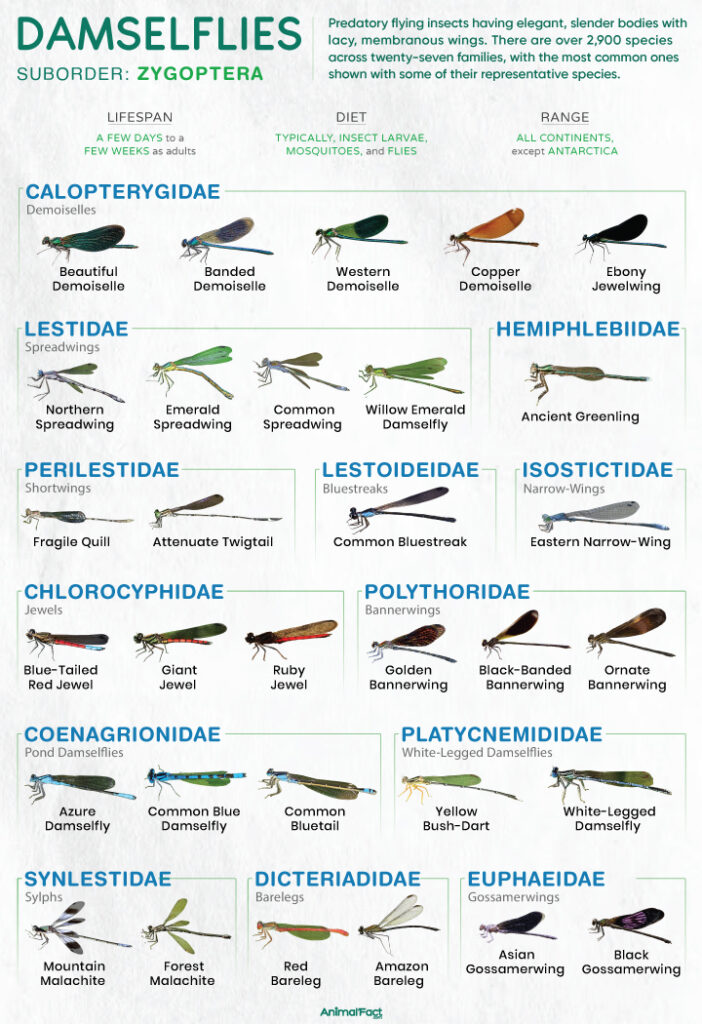

Damselflies are a group of predatory flying insects that constitute the suborder Zygoptera. They look similar to dragonflies (infraorder Anisoptera), but are typically smaller, with thinner bodies. The name ‘damselflies’ reflects their elegant, slender bodies with lacy, membranous wings. When at rest, most damselflies hold their wings together over the abdomen, unlike dragonflies, which have their wings horizontally open.

This group represents an ancient lineage of insects, with the earliest damselfly fossils dating to the Kimmeridgian Age of the Late Jurassic Period (around 152 million years ago). As of 2021, over 2,900 living species of damselflies are found in the world.

These insects are hemimetabolous, lacking a pupal stage, and their eggs develop into adults via nymphal stages. They typically breed in freshwater habitats and serve as a bioindicator of water pollution.

Their wingspans range between 0.71 in (1.8 cm) in the smallest damselflies and 7.5 in (19 cm) in large males of the blue-winged helicopter (Megaloprepus caerulatus).

Like all other insects, damselflies have three distinct body segments (tripartite): the head, thorax, and abdomen, encased in a hard chitinous exoskeleton.

The top of the head bears three simple eyes or ocelli and a tiny pair of bristle-like antennae. The antennae, surprisingly, have no olfactory function but are believed to help measure air speed.

On either side of the head are a pair of large compound eyes. These eyes are more widely separated and smaller when compared to those of a dragonfly.

The lower lip or labium of the mouth bears an extensible organ that helps capture prey easily.

This segment is subdivided into a prothorax and a synthorax, which is the fused mesothorax and metathorax. The prothorax bears the first pair of legs, while the synthorax bears the other two pairs of legs.

The thorax also bears two pairs of membranous, intricately veined wings. In damselflies, the forewings and hindwings are similar in size and shape, unlike dragonflies, whose hindwings are noticeably broader than their forewings. Some families, like Lestidae, Platycnemidae, and Coenagrionidae, have colorless wings, whereas Calopterygidae and Euphaeidae have coloured wings.

All damselflies possess a small, quadrangular, colored marking located near the tip of each wing, along the leading edge. The size, shape, and color of this marking vary between different species, thereby acting as a species identifier.

Like dragonflies, the abdomen of damselflies is long and slender, having ten segments. In males, the secondary genitalia are found on the undersides of segments two and three, while the primary genitalia are located on the ninth segment. In females, the genital opening is found on the underside between segments eight and nine.

Both sexes bear paired appendages called cerci on the tenth segment. In males, short and pointed appendages called paraprocts are found at the end of the abdomen, below and medial to the cerci.

Depending on the species, these insects display a wide range of colors, from metallic to pastel tones. Many pond damselflies exhibit different shades of blue and green. Some species, such as the large red damselfly (Pyrrhosoma nymphula) and American rubyspot (Hetaerina americana), are notably reddish.

In Eurasian bluets (Coenagrion), the males are bright blue with black markings, whereas the females are predominantly green or brown.

According to Dijkstra et al. 2013, 2014, there are 27 families of damselflies, as listed below.[1]

Further molecular analyses (2021) proposed the addition of seven new families (Priscaagrionidae, Tatocnemididae, Protolestidae, Mesagrionidae, Mesopodagrionidae, Amanipodagrionidae, and Rhipidolestidae) to the existing list. However, this revised classification has not yet achieved global consensus.

These insects are found on all continents except Antarctica, with most species having smaller ranges compared to dragonflies, which have wider distributions. Most damselflies tend to live within a short distance of where they hatched. However, some, like forktails (Ischnura), disperse widely. For instance, the Rambur’s forktail (Ischnura ramburii) has been spotted on oil rigs far out in the Gulf of Mexico.[2]

Damselflies are found mainly near shallow freshwater habitats, such as wetlands, where their nymphs develop. However, a few species, such as the Rambur’s forktail, can breed in brackish water.[3]

Different species inhabit a range of habitats that vary in water depth, flow dynamics, and pH levels. For instance, the European common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum) occupies acidic waters. In contrast, the scarce blue-tailed damselfly (Ischnura pumilio) requires base-rich waters with a slow flow rate.

A few species are found in some unimaginably unique habitats. For example, in the rainforest of northwest Costa Rica, the species Mecistogaster modesta breeds in phytotelmata, which are small water-filled cavities in epiphytic plants.[4] The cascade damselfly (Thaumatoneura inopinata) lives in waterfalls found in moist tropical or subtropical forests in Costa Rica.

Damselflies are carnivorous predators, but their diet varies with their different life stages. Nymphs feed primarily on mosquito larvae, midge larvae, mayfly nymphs, water fleas, and worms. Adults, on the other hand, are aerial hunters and feed mostly on flying insects. Their prey includes flies, mosquitoes, gnats, moths, midges, small beetles, and small butterflies.

In tropical South America, some helicopter damselflies, such as Pseudostigma aberrans, specialize in feeding on spiders, plucking them from their webs.[5]

While adult damselflies live only for a few days to several weeks, nymphs live longer, typically for several months to up to 3 years, depending on the species.

Most species of damselflies reproduce sexually. However, females of the species citrine forktail (Ischnura hastata) reproduce asexually through parthenogenesis.[7]

The male tries to court the female using a combination of visual displays and aerial acrobatics. He also tries to fend off rival males in the process. Once ready to mate, the male transfers a packet of sperm (spermatophore) from his primary genital opening on segment 9 to his secondary genitalia on segments 2 and 3. He then grasps the female by the head using the claspers at the end of his abdomen. The pair flies in tandem, with the male leading and eventually perching on a twig or stem. Once settled, the female gradually curls her abdomen and reaches the male’s genitalia to collect the sperm. Simultaneously, the male grips the female’s head, forming a heart or wheel posture. The pair remains in the same posture as the female prepares to lay her eggs.

The eggs are typically laid inside plant tissues, with some species, like the willow emerald (Chalcolestes viridis), preferring only woody plants for this purpose. Other species, such as Lestes sponsa, lay their eggs underwater and submerge themselves for extended periods.[8]

Being hemimetabolous insects, damselflies, like dragonflies, lack a pupal stage; instead, the egg develops into an adult through nymphal stages. As the egg hatches, it emerges as a nymph, which is typically aquatic in almost all damselfly species. Only in a few species, such as Megalagrion oahuense, are the nymphs terrestrial in the early stages.

The nymphs possess a flat labium (a toothed mouthpart on the lower jaw) that they use to feed on their prey. They breathe using three large external, fin-like gills on the tip of the abdomen. When swimming, nymphs propel themselves with fish-like undulations, using their gills much like fish use their tail fins.

A nymph undergoes about a dozen moults, develops wingpads, and climbs out of the water onto a plant stem. Once perched, the skin on its thorax splits, metamorphosing into an adult. The hemolymph rushes into its small wings, which then become fully extended. Gradually, the stomach expands, too, followed by hardening and darkening of the exoskeleton in a few days.

Adults typically emerge during the daytime, under cool conditions.

Both adults and nymphs fall prey to various invertebrate predators, including water spiders, water beetles, backswimmers, giant water bugs, and dragonflies. They also become targets of vertebrate predators, including frogs, fish, and birds.

Most damselflies are parasitized by both ecto- and endoparasites. For instance, water mites stick to the bodies of both adults and nymphs, while gregarine protozoans are found in the gut.