Dobsonflies are large, primarily nocturnal insects that belong to the subfamily Corydalinae. Together with fishflies (subfamily Chauliodinae), they constitute the family Corydalidae. In many species of dobsonflies, the males have strikingly large mandibles, while their female counterparts have shorter ones.

They are holometabolous insects, undergoing four distinct life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The larval stage, commonly known as the hellgrammite, is aquatic and predatory, often clinging to rocks in fast-flowing streams. In contrast, the adults are short-lived and do not feed, spending much of the day hiding under leaves or in rock crevices.

Since the larvae require clean, oxygen-rich water for survival, they serve as excellent bioindicators of water pollution.

On average, dobsonflies measure around 2 to 3.5 in (5 to 9 cm) in body length, excluding the mandibles. Their average wingspan is about 4.5 to 7 in (12 to 18 cm).

According to the Guinness World Records, the world’s largest insect by wingspan is the dobsonfly Acanthacorydalis fruhstorferi, with a wingspan of 8.5 in (21.6 cm).

Like all insects, dobsonflies have a tripartite body, divided into head, thorax, and abdomen.

The head is equipped with strong mandibles, compound eyes, and long, filamentous antennae. In males of the genera Acanthacorydalis, Corydalus, and Platyneuromus, the mandibles are especially elongated and sickle-shaped. Since these mandibles are too large, they are not used for biting; instead, they are believed to play a role as a secondary sexual characteristic that helps in sexual selection by females. The females, in contrast, possess short, heavily sclerotized mandibles, which are strong enough for biting predators.

The thorax is subdivided into pro-, meso, and metathoracic regions, with each subsegment bearing a pair of legs. Additionally, the thoracic region bears two pairs of large, membranous, highly veined wings. Despite having wings, adult dobsonflies are weak fliers.

The abdomen typically has 10 visible segments, each covered dorsally by hard tergites and ventrally by sternites. Both males and females have a pair of short, sensory appendages, the cerci, at the tip of the abdomen.

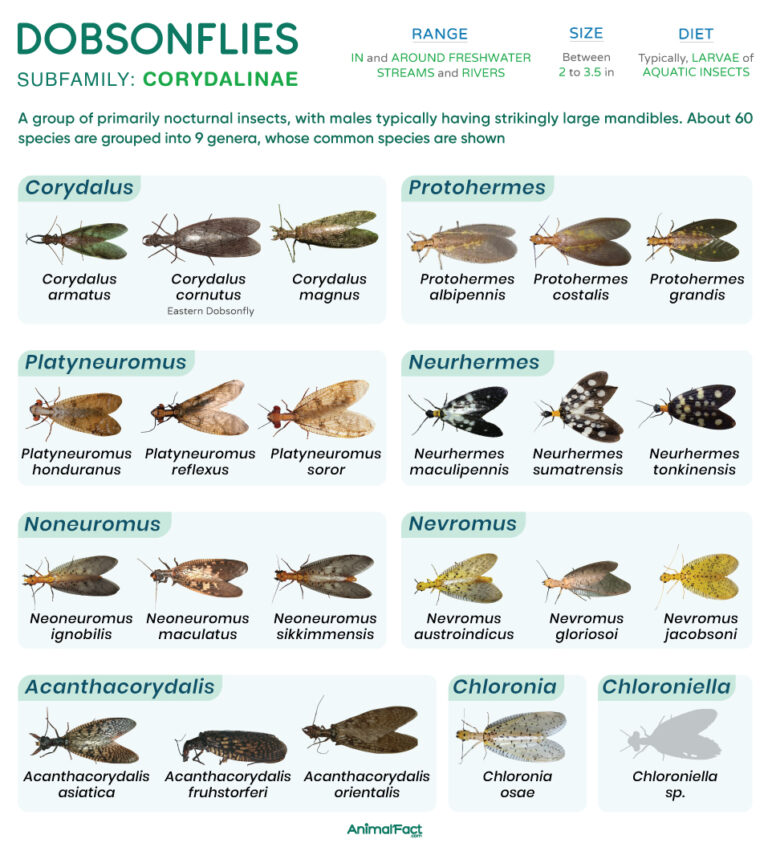

Around 60 species are classified into 9 genera.

These insects are found in the Americas, Asia, and South Africa. In North America, only four species of the genus Corydalus occur north of Mexico, with the most common being the eastern dobsonfly (Corydalus cornutus). In contrast, three genera with over 50 species are described from the Neotropics.[1]

Their larvae are aquatic, found in clean, well-oxygenated freshwater streams and rivers. They prefer fast-flowing waters (riffles) with rocky bottoms, where they hide under stones. Adults stay close to aquatic habitats, often hidden among vegetation.

Dobsonfly adults are short-lived and typically do not feed at all in the wild. Those that do, consume honey-water, nectar solutions, or fruit juices in captive habitats, such as laboratories.[2]

In contrast, dobsonfly larvae are active hunters that primarily feed on larvae of aquatic insects, such as mayflies, caddisflies, blackflies, and stoneflies. They may opportunistically feed on small crustaceans (like amphipods, isopods), worms (aquatic oligochaetes), as well as tadpoles.[3]

While hellgrammites typically live between 1 and 5 years, adult dobsonflies live only a few days to about a week.[4]

Although the reproductive behavior of a few species has been studied, males of the genus Corydalus have been observed to engage in elaborate courtship displays before mating. They try to outcompete rival males by placing their long mandibles underneath the opponent’s body, attempting to flip them into the air. Once the most superior male is established, he approaches the female, trying to touch her with his antennae. Although the female initially reacts aggressively, she eventually allows him to come closer and place his mandibles over her wings at a perpendicular angle.

During copulation, particularly in members of the genus Protohermes, the male attaches a large, globular spermatophore (a packet of sperm) to the female’s genitalia. The spermatophore comprises a large gelatinous mass and a smaller seminal duct containing the sperm. Once the spermatophore has been transferred, the female spreads her legs wide apart, curls the abdomen under the chest, and consumes the gelatinous part of the spermatophore.

Females usually lay their eggs between May and September, forming coin-sized masses that contain around a thousand gray, cylindrical eggs, each measuring about 1.5 mm long and 0.5 mm wide. The egg mass is encased in a layer of a chalky, white substance, which prevents the eggs from overheating and desiccation.

Within 1 to 2 weeks after the eggs are laid, they hatch into larvae. These larvae have elongated, dark, segmented bodies with paired lateral filaments and gill tufts for respiration. They also possess well-developed jaws used for feeding on aquatic prey. To cling to rocks underwater, they are also equipped with hooked anal appendages or prolegs.

The larvae undergo 10 to 12 molts (over 1 to 5 years), and as they mature, they crawl out of the water onto moist soil or under streamside debris. They stop feeding and build a chamber, where they remain inactive for several days to weeks as prepuae. They eventually transform into pupae, developing wings, large mandibles, and the internal organs of the body.

After several days, or even weeks, the pupal cuticle splits, and the adult dobsonfly emerges, typically at night or in the early morning.

Since hellgrammites spend years in water, they are vulnerable to a range of aquatic and semi-aquatic predators, such as fish (including trout and bass), frogs, and birds (such as herons and kingfishers). They also become targets of dragonfly nymphs and giant water bugs.

Adults, on the other hand, are preyed upon by birds, bats, and orb-weaving spiders.[5]