Praying mantises, simply called mantises, are insects that constitute the order Mantodea. They are closely related to cockroaches and termites, collectively comprising the superorder Dictyoptera.

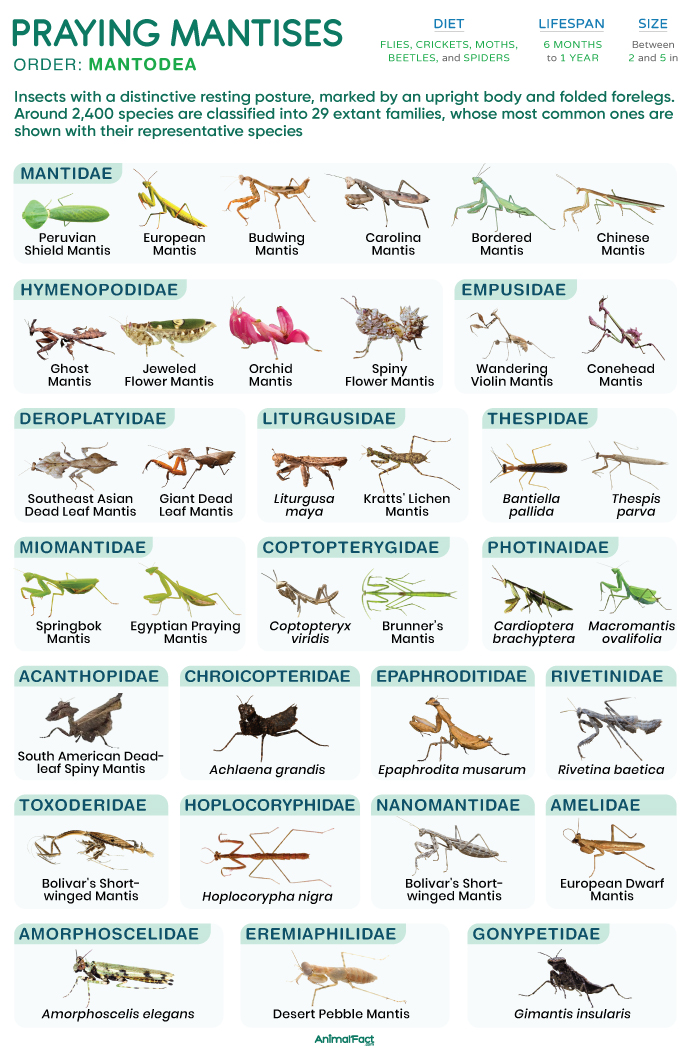

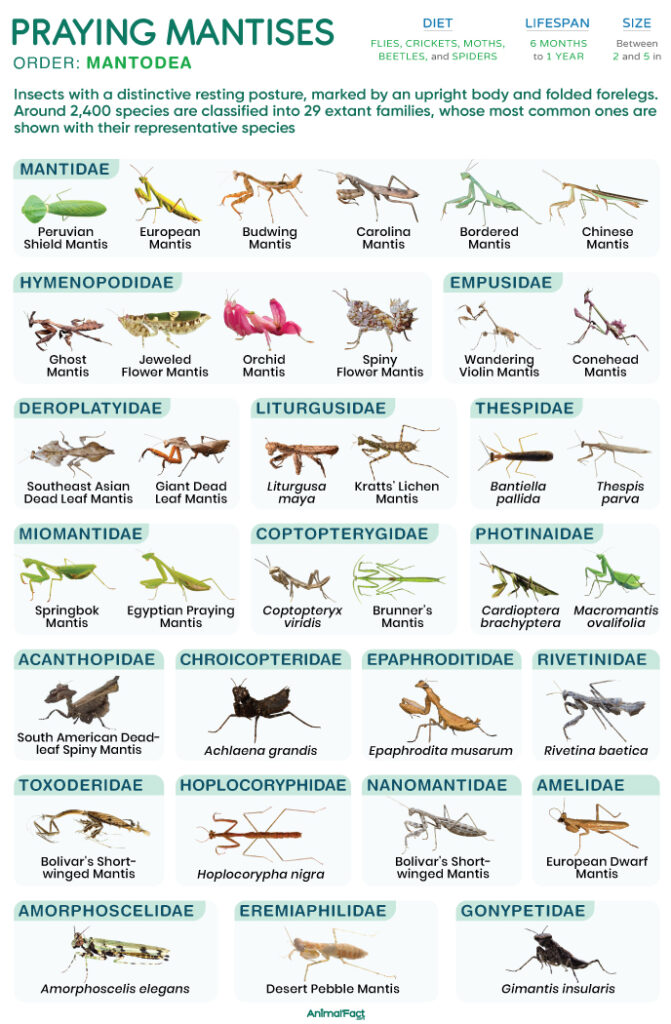

These insects derive their name from their distinctive resting posture, marked by an upright body and folded forelegs. The forelegs are specialized raptorial limbs, equipped with spines that enable them to seize and firmly grasp their prey. Additionally, they are characterized by a highly mobile, triangular head with large compound eyes and stereoscopic vision.

On average, adult praying mantises range between 2 and 5 in (5 and 12 cm). One of the largest species, the giant rainforest mantis (Hierodula majuscula), measures between 2.7 and 4.3 in (7 and 11 cm), whereas the smallest, Bolbe pygmea, is only around 0.3 in (1 cm) long.

Generally, females tend to be larger than males.

Praying mantises have slender, elongated bodies with three distinct regions: the head, thorax, and abdomen, the characteristic tripartite arrangement of all insects. Their bodies are covered in a tough, flexible exoskeleton composed of chitin, which is typically green or brown in color.

The head is notably triangular, with a beak-like snout, and a pair of thread-like antennae. It is supported by an extremely flexible neck, which in most species swivels about 180° side to side, a capacity unique to praying mantises.[1]

Their pair of large, bulbous compound eyes is seated laterally on the head, providing a wide binocular field of vision. Additionally, they possess three simple eyes or ocelli.

Each compound eye comprises up to 10,000 visual units called ommatidia. A small area, the fovea, provides high resolution for examining prey, while the peripheral ommatidia are more sensitive to motion. On detecting movement, the mantis quickly turns its head to align the object with the fovea. Unlike humans, these insects possess stereoscopic (3D) vision at close range.[2]

The thoracic region is subdivided into three segments: pro-, meso, and metathorax, with the prothorax being visibly longer than the other two segments. Each segment bears a pair of walking legs. Typical of most insects, each leg bears five segments: coxa, trochanter, tibia, femur, tarsus.

While the coxa and trochanter of most insects form a small, inconspicuous base, in praying mantises, these segments are greatly elongated in the forelegs, forming a segment nearly as long as the femur. In most species, the base of the femur has a specialized series of discoidal spines, typically four in number. These spines are preceded by tooth-like tubercles, small projections that help prevent the prey from slipping out of the grip. The tibia bears an opposing row of tubercles, ending in a sharp apical claw near its tip. When the femur and tibia snap together, these structures interlock, trapping the prey within the space.

In winged species, the mesothorax and metathorax bear the forewings (tegmina) and hindwings. The forewings are narrow and leathery, functioning as protective shields for the more delicate hindwings folded beneath them. However, females of some species, such as the desert pebble mantis (Eremiaphila zetterstedti), are wingless (apterous) or may have reduced, non-functional wings (brachypterous).

The abdominal region is elongated and flexible, usually consisting of 10 visible segments. In females, the abdomen is broader and heavier, whereas in males it is slimmer and more tapered. This region contains the respiratory openings (spiracles) as well as the digestive and reproductive organs.

In both males and females, the abdomen ends in a pair of sensory appendages known as the cerci.

Mantises were first grouped with stick insects (Phasmatodea) in the order Orthoptera, alongside cockroaches (now Blattodea) and ice crawlers (now Grylloblattodea). They were later combined with cockroaches and termites under the order Dictyoptera, eventually being recognized as a distinct order, Mantodea.

The name of the order was coined by the German entomologist Hermann Burmeister in 1838. It derives from the Ancient Greek words mantis (prophet) and eidos (form or type), hinting at the distinctive, prayer-like posture of its members.

As of 2019, over 2,400 species of praying mantises are classified into 29 extant families.

These insects have a nearly cosmopolitan distribution, found on all continents except Antarctica. They are particularly diverse in rainforests and savannas, but are also found in grasslands, woodlands, arid and semi-arid regions, as well as gardens and agricultural fields. Most species tend to remain camouflaged against the surrounding vegetation, making them difficult to spot.

Praying mantises are generalist predators of other insects, such as flies, crickets, grasshoppers, moths, beetles, and butterflies, as well as other arthropods, including spiders. Their nymphs primarily feed on small, soft-bodied insects such as aphids, small gnats, and caterpillars.

On rare occasions, some species, such as the Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis), have been reported to feed on ruby-throated hummingbirds.[3] Similarly, in exceptional cases, Hierodula tenuidentata has been observed feeding on fish, particularly guppies.[4]

They tend to drink water droplets from leaves.

Although most species are diurnal, a few species, such as many members of the genus Hierodula, are crepuscular or nocturnal.[5]

Most mantises are ambush predators, stealthily waiting for their prey to approach. Once within reach, they quickly grasp the prey using their raptorial forelegs. However, some species, such as members of Entella, Ligaria, and Ligariella, are active foragers, running over dry ground in search of their prey.

The females of most predatory mantises (about 90%) prey upon their male counterparts (sexual cannibalism) before, during, or after mating. They tend to bite off their heads first, followed by the rest of the body. If mating has already begun, the male’s body may continue to copulate due to reflexive neural activity in the abdomen.

Studies suggest that females on poor diets are more likely to eat their mates, indicating that cannibalism provides valuable nutrients for egg production. For males, being consumed can enhance reproductive success, as it often prolongs copulation and increases chances of fertilization.[7]

Depending on the species and environmental conditions, praying mantises typically live around 6 months to a year.

In the tropics, praying mantises can mate any time of the year, but those in temperate regions typically mate in autumn. The females emit pheromones to attract males, who locate them using their antennae. The male approaches the female cautiously, climbing onto her back and grasping her thorax with its forelegs. Once mounted, the male deposits sperm into the female’s reproductive tract, which is then stored in a sac-like spermatheca. The female eventually uses the stored sperm to fertilize the eggs.

Although most species reproduce sexually, a few, such as Brunner’s mantis (Brunneria borealis), reproduce parthenogenetically, where the embryo develops from unfertilized eggs.[8]

Depending on the species, the female lays between 10 and 400 eggs at a time in a frothy mass. The froth hardens into a protective capsule, which, collectively with the egg mass, is called an ootheca. The female may attach the ootheca to a flat surface, wrap it around a plant, or even deposit it on the ground.

The eggs hatch into nymphs in about 10 days to 12 weeks, depending on the species. The nymphs, which resemble miniature adults, undergo 5 to 10 molts. During the final molt, the nymph sheds its exoskeleton (ecdysis), emerging as an adult.

The predators of praying mantises vary with their life cycle stages. For instance, the eggs of the ootheca become targets of birds, spiders, ants, and small rodents, such as mice. Their adults fall prey to birds, including sparrows, shrikes, and crows, as well as orb-weaving spiders, bats (only during nocturnal flight), frogs, lizards, and small mammals (such as shrews).

For cannibalistic species, females eating their male counterparts also counts as predation.