Termites are a group of eusocial insects that constitute the infraorder Isoptera, which falls within Blattodea, an order comprising cockroaches. They are found on all continents except Antarctica, with the highest diversity in the tropical region, where they account for about 10% of the animal biomass.

These insects share similarities with ants, as well as certain bees and wasps, in their colonial organization, which is marked by a distinct caste system. Most individuals within a colony are wingless workers, followed by wingless soldiers that serve a defensive role. The only reproductively capable members of the colony are a monogamous pair of winged king and queen, who fly for a very brief period, settle on a substrate, mate, and shed their wings. The queen termite has exceptional egg-laying capabilities, and the eggs eventually hatch into nymphs. These nymphs can develop into any of the castes, depending on the environmental conditions and the colony requirements.

They primarily feed on cellulose found in wood and thus inflict damage to agricultural plants, buildings, and furniture.

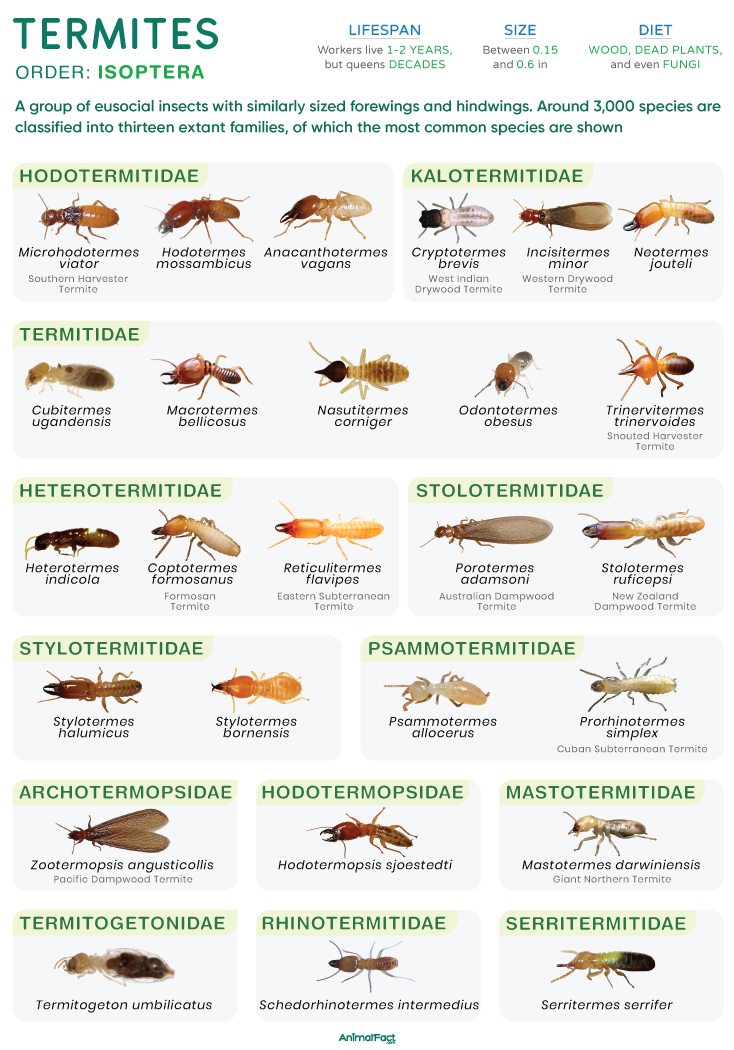

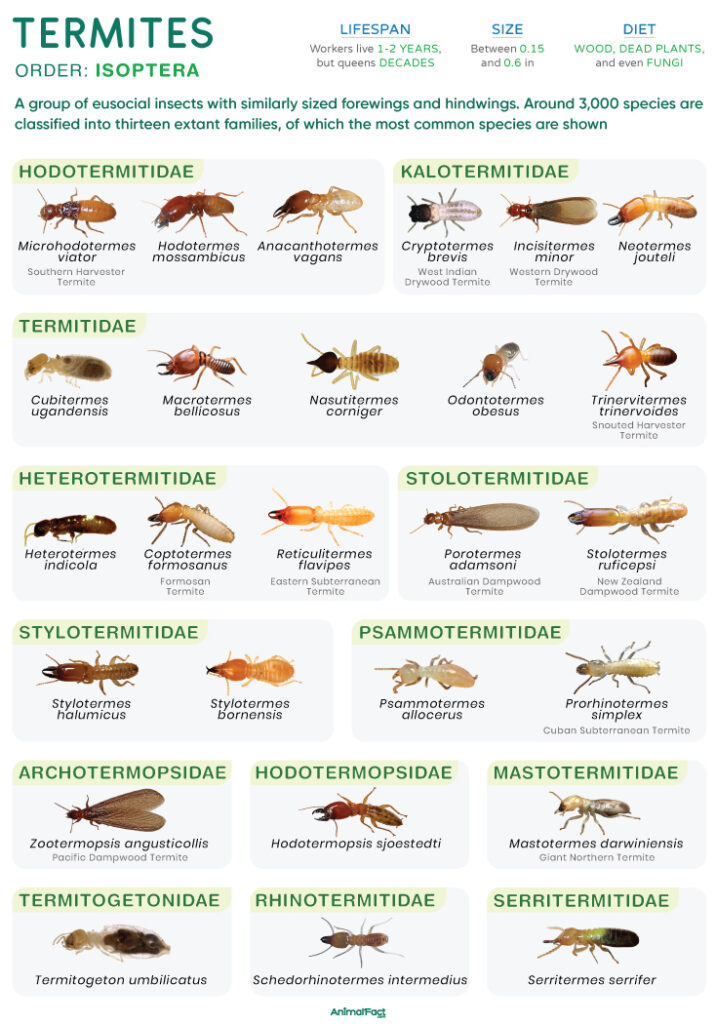

On average, these insects measure between 0.15 and 0.6 in (4 and 15 mm). However, the queens of the largest extant species, Macrotermes bellicosus, are between 4.5 and 6 in(11 and 15 cm) long.

Among the smallest species is the Indo-Malaysian drywood termite (Cryptotermes cynocephalus), the soldiers of which measure between 0.09 and 0.14 in (2.5 and 3.7mm).

Like all insects, termites have a tripartite body plan, comprising three segments: head, thorax, and abdomen. They are covered by a soft and thin cuticle, which is typically pale or creamy white, lacking melanin due to their hidden lifestyle.

This segment bears a pair of bead-like, sensory antennae, which help detect touch, taste, odours, heat, and vibration. Each antenna has three segments: a scape, a pedicel, and the flagellum.

The mouthparts include maxillae, a labium, and a set of chewing-type mandibles. The maxillae and labium bear sensory palps that help sense the food these insects handle.

While workers and soldiers are blind, the reproductive individuals bear a pair of compound eyes along with lateral ocelli (simple eyes). The ocelli are, however, absent in members of the families Hodotermitidae, Termopsidae, and Archotermopsidae.

The thoracic region is subdivided into three subsegments: pro-, meso, and metathorax, each bearing a pair of legs. Each leg has five segments: the coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, and a clawed tarsus.

Only reproductive individuals possess two pairs of wings. The forewings are attached to the mesothorax, while the hindwings arise from the metathorax. Unlike in ants, the forewings and the hindwings of termites are almost equal in length.

The abdominal region consists of ten segments, each covered by hardened plates on the dorsal (tergites) and ventral (sternites) sides. The final segment of the abdomen bears a pair of short, specialized appendages called cerci, which function in detecting air currents and vibrations, as well as in holding the mate during copulation.

In reproductive females, the paired ovaries extend across abdominal segments 3 to 7, while in males, the testes are located within segments 4 to 6 of the abdomen. The external genital opening in both males and females is found on segment 9.

The males lack an intromittent (sperm-delivering) organ. Females of the family Mastotermitidae possess an ovipositor for laying eggs.[1]

The name of the infraorder, Isoptera, stems from the Greek words iso (meaning equal) and ptera (meaning winged), which hint at the nearly equal size of the fore and hind wings. On the other hand, the common name, termite, comes from the Latin and Late Latin word termes, which refers to a ‘woodworm’ or ‘white ants.’

Around 3,000 species are divided into 13 extant families.

Although termites were initially grouped under a separate order, Isoptera, scientists began to suggest (as early as 1934) that they were closely related to the cockroach genus Cryptocercus, which comprises wood roaches. This hypothesis was finally confirmed in 2008 through DNA analysis of 16S rRNA sequences, which revealed that termites are phylogenetically closest to wood roaches and should be nested within the order Blattodea, the group comprising all cockroaches.

The earliest unambiguous termite fossils date back to the Early Cretaceous Period (around 130 million years ago). However, indirect evidence suggests a potentially earlier origin. For example, the extinct mammaliaform Fruitafossor is believed to have fed on termites, indicating their origin during the Jurassic or even Triassic Periods.

The presence of termite species varies across the continents.

These insects prefer warm, humid environments, with the highest diversity in tropical rainforests. They are divided into the following categories based on the habitats they occupy:

These insects primarily feed on cellulose, which they obtain from wood, plant matter, humus, and other vegetative materials such as paper, cardboard, hemp, and cotton.

Some species, such as Gnathamitermes tubiformans, exhibit seasonal preferences in the plants they consume. For example, this species feeds on red three-awn (Aristida longiseta) in early summer, buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides) from late summer to fall, and blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) throughout spring, summer, and fall.[4]

Termites live in colonies that exhibit a well-organized hierarchy, comprising three castes: reproductives, workers, and soldiers. Depending on the species, the colony size may vary from a hundred to millions of individuals.

Both the male and the female reproductives release pheromones that are transmitted through the sharing of food. These pheromones inhibit the development of reproductive parts in workers and nymphs, hence suppressing the development of other reproductives within the colony.

Since most termites are blind, they communicate through chemical, mechanical, and pheromonal cues.

As eusocial insects that live in colonies, face-offs are quite common in termites. For instance, among the reproductive castes, the neotenic females of some species often compete with each other to become the dominant queen.

Conflicts also arise when the underground foraging tunnels of termites intersect. Some species, such as the Formosan termite (Coptotermes formosanus), have been found to engage in ‘suicide cramming,’ in which individuals squeeze themselves inside the tunnels and die, blocking them and effectively preventing rival termites from entering.[7]

On sensing danger, soldier termites bang their heads against the tunnel walls or floor, creating vibrations that alert their nearby nestmates. They also bump into other termites, helping to spread alarm pheromones.

Some species, like Globitermes sulphureus, commit suicide by rupturing a highly specialized frontal gland beneath the surface of their cuticle (autothysis). The rupture results in the release of a toxic, yellow fluid that becomes very sticky on contact with the air, thereby helping entrap the intruders quickly.[8]

These insects build three primary types of nests: subterranean, epigeal, and arboreal. They use a mixture of soil, chewed wood or plant material, saliva, and feces to build these nests.

Subterranean species, such as the Eastern subterranean termite, build their nests underground, whereas members of the genus Macrotermes construct elaborate mounds above the ground, which can reach heights of 26 to 29 ft (8 to 9 m). In contrast, species belonging to the genus Microcerotermes typically build arboreal nests on the trunks and branches of trees.

The lifespan of termites varies with the stage of their life cycle. For instance, workers and soldiers typically survive only about 1 to 2 years, while queens of some species may live between 30 and 50 years under suitable conditions.

To begin the reproductive process, winged adults called alates or swarmers fly away from the parent nest (nuptial flight) and pair up. Although the swarming season varies with species and environmental conditions, most termites swarm during spring and early summer. They search for a suitable site to land, excavate a large nuptial chamber, and seal its entrance to mate inside. Since male termites lack a copulatory organ, sperm are typically released through a median pore on the ninth sternite and transferred to the female, who stores them in the spermatheca, the sperm-storing organ. The pair sheds the wings immediately after mating.

After fertilization, the queen lays only about 10 to 20 oval, pale white, or translucent eggs. Over 2 to 5 years, as the colony expands, the queen’s egg-laying capacity increases significantly, accompanied by a marked enlargement of her abdomen (phylogastry). At this stage, in some species, such as Odontotermes obesus, the queen is capable of laying over 30,000 eggs a day.[9]

As hemimetabolous insects, the eggs of termites hatch into nymphs, instead of a pupal stage. The nymphs resemble pale, miniature adults, molting several times to form adults. Depending on environmental cues, pheromones, and hormonal levels, the nymphs may develop into workers, soldiers, or reproductive adults (developmental plasticity). The first nymphs typically develop into workers and soldiers, whereas those that hatch in mature colonies tend to become winged adults.

Termites have several predators, including arthropods, such as ants, centipedes, cockroaches, crickets, dragonflies, scorpions, and spiders, as well as lizards, frogs, and toads. Additionally, they are preyed upon by various birds and mammals, including aardvarks, aardwolves, anteaters, bats, bears, bilbies, echidnas, foxes, galagos, numbats, pangolins, and mice. Sloth bears and chimpanzees also break open termite mounds.

Among all termite predators, ants are the most notable. Certain species, such as Paltothyreus tarsatus, Eurhopalothrix heliscata, and Tetramorium uelense, are known to specialize in preying on these insects. Other ants that consume termites include members of the genera Camponotus, Crematogaster, Cylindromyrmex, Odontomachus, and Acanthostichus, among others.