True crabs are crustaceans belonging to Brachyura, an infraorder within the order Decapoda. They are characterized by a broad, chitinized carapace that shields the thoracic region, a reduced abdomen tucked beneath the carapace, and five pairs of legs. The first leg pair is modified into prominent claws or chelae used for defense and feeding. Most true crabs move in a distinctive sideways gait because their legs are angled outward and hinged to push more efficiently to the side than forward.

Comprising over 7,000 species worldwide, true crabs inhabit a wide range of marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats.

Their sizes vary by species. For example, one of the smallest, the pea crab (Pinnotheres pisum), measures barely 0.5 in (12.7 mm) across, while the largest species, the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi), has the greatest leg span of any known arthropod, reaching up to 12 ft (3.6 m) from claw to claw. The latter also has a carapace width of about 16 in (406 mm) and weighs around 42 lb (19 kg).[1]

True crabs have a bilaterally symmetrical body separated into two broad segments: the cephalothorax and the abdomen. The body is encased in a flattened, chitinous exoskeleton, which acts as its first line of defense.

A fusion of head and thorax, the cephalothoracic region bears a pair of compound eyes on movable stalks, two pairs of sensory antennae, and the mouthparts. They have one pair of mandibles, two pairs of maxillae, and three pairs of maxillipeds. While the maxillipeds help hold, tear, and transfer food to the mouth, the maxillae and mandibles are used in handling the prey.

They generally have five pairs of legs (a total of ten, hence decapods), with the first pair, known as chelipeds, bearing claws or chelae at the tip. The chelipeds are used for defense, capturing food, and communication.

The next four pairs of legs are used for walking. In swimming species, the last pair is modified into paddle-like structures for swimming.

Also known as the pleon, this region is highly reduced, almost tail-like, and remains tucked beneath the cephalothorax. In males, it is narrow and triangular, whereas in females, it is broader and more rounded, as it is designed to carry eggs.

The underside of the abdomen bears small paired appendages called pleopods. In males, the pleopods are modified to transfer sperm during mating, while in females, they are used to hold and aerate eggs during incubation.

Although ‘true crabs’ refer to members of the infraorder Brachyura, several other crustaceans are also called ‘crabs’ because they look crab-like, even though they are not Brachyura. For example, hermit crabs, porcelain crabs, and king crabs belong to the infraorder Anomura (sister group) but are still commonly referred to as ‘crabs.’ Despite their similar appearance, these groups are not true crabs, since their crab-like body shape evolved independently through a process known as carcinization.

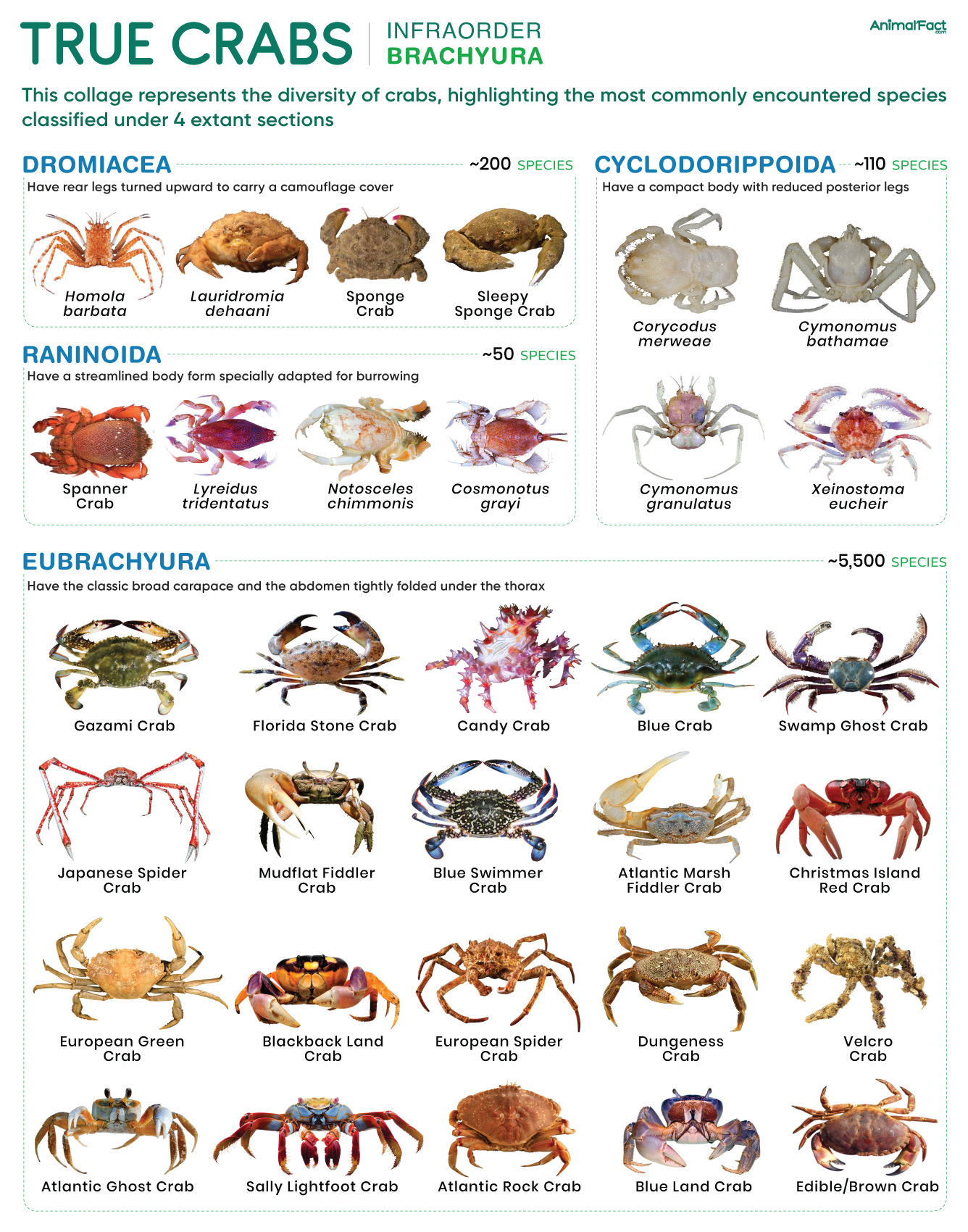

All species of the infraorder Brachyura are subdivided into 4 extant and 1 extinct sections.

The oldest unambiguous fossils of true crabs (belonging to the genus Eocarcinus) date back to the Early Jurassic Period, represented only by dorsal carapaces. They began to diversify during the Late Jurassic, with their diversity reaching its peak in the Cretaceous Period.

Most true crabs are marine, found in all oceans of the world. However, around 1,300 species live exclusively in freshwater environments, such as rivers, lakes, and streams, especially in Asia, Africa, and South America.[2] In fact, several species, such as the coconut crab (Birgus latro), are terrestrial and live in coastal forests.[3]

True crabs are opportunistic omnivores that feed on both plant and animal matter, depending on what is available. Depending on the species and the habitat they occupy, their diet includes algae, mollusks, worms, other crustaceans, fungi, bacteria, and detritus.

For example, the striped shore crab (Pachygrapsus crassipes) typically consumes green algae, red algae, brown seaweed, and diatoms.[4] On the other hand, coconut crabs primarily feed on fleshy fruits, nuts, seeds, and carrion.[5] Many species, such as the Dungeness crab (Metacarcinus magister), are typically carnivorous, eating bivalves, shrimp, small fish, isopods, and amphipods.[6]

The lifespan of true crabs varies with species. For instance, blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) generally live for 3 or 4 years, while the coconut crab may survive for as many as 60 years or more in the wild.[7][8] Others, such as members of the genus Potamon, live around 10 to 12 years.[9]

Depending on the species and habitat, true crabs attract their mates using chemical, visual, acoustic, or vibratory cues. Aquatic species primarily release pheromones into the water to attract the opposite sex, whereas terrestrial and semi-terrestrial true crabs rely more on visual displays. For example, male fiddler crabs wave their large pincers at the females to draw their attention.

Once the pair forms, most true crabs mate belly-to-belly, and the males transfer their sperm inside the female’s body. The sperm remains stored inside her body for a long time before it fertilizes the eggs internally.

Once the eggs are fertilized, the female attaches them to the underside of her abdomen (giving them a berried appearance), beneath a protective flap, the tail flap, using a sticky secretion. In 1 to 4 weeks, when development is complete, the embryos hatch as planktonic zoea larvae, which the females then release into the water.

The zoea larvae possess defensive spines, are free-swimming, and drift with oceanic currents, feeding on microscopic organisms. They undergo 6 to 8 molts, after which they transform into the megalopa larval stage.

The megalopa resembles a small adult crab but with an extended tail. In 2 to 6 weeks, through a final molt, it transforms into a juvenile crab, switching from planktonic to benthic life.

Because a crab’s hard exoskeleton doesn’t stretch, the juveniles undergo multiple molts as they increase in size. They secrete hormones that help soften and loosen the old shell as a new rudimentary shell forms underneath. Through consecutive molts, the juveniles transform into adults.

These arthropods face a wide range of predators in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats. For example, in the oceans, they are hunted by large predatory fish, including groupers, cod, and triggerfish. Moreover, seabirds like gulls, herons, and oystercatchers prey on true crabs along the shore, often dropping them from heights to break their shells. Some marine mammals, such as sea otters and seals, also consume true crabs.

On land, they are hunted by raccoons, foxes, and monkeys. Humans, however, remain among their most significant predators, harvesting them extensively for their meat.